I do not remember where I was when I heard that the Thirty Fifth President of the United States of America had been assassinated, but I do remember the subsequent media coverage of the death, the funeral, the arrest and shooting of Lee Harvey Oswald, the conspiracy theories, the conjuring of Camelot, and the strange outpourings of public adulation and grief. No wonder that two other notable deaths on 22 November 1963 passed virtually unnoticed.

John F. Kennedy (1917-63) was the son of Joseph Kennedy who had amassed a fortune through stock market manipulation, property deals and bootlegging. It was trust funds set up by his father that provided Jack Kennedy with financial independence and enabled him to run his successful campaign to become president, notwithstanding an undistinguished record in the Senate. His father’s contacts, including the mafia boss, Sam Giancana, allegedly provided support following a deal with Joseph that if his son were elected he would “lay off organised crime.” Giancana’s control of the Teamsters’ Union and their votes, and judicious use of threats and fraudulent voting, helped deliver Kennedy’s narrow Presidential victory.

JFK’s time as president (1961-63) was defined by the fiascos and iniquities of a foreign policy engendered by Communist paranoia combined with arrogant Imperialism. In April 1961 he unleashed the Bay of Pigs invasion led by CIA paramilitary officers who tried to foment an uprising to overthrow Castro’s government in Cuba. They were defeated in two days. There followed the equally unsuccessful Operation Mongoose characterised by terrorist attacks on civilians, the destruction of crops, mining of harbours and farcical assassination attempts directed against Castro. Abortive efforts were made to keep this operation secret to avoid repercussions from the United Nations.

On Kennedy’s watch American involvement in Vietnam built up: military advisers were sent to the country along with political and economic support for the Diem regime whose forces were funded and trained by the CIA . Under the crude social engineering of the Strategic Hamlet Programme peasants were forcibly relocated away from Viet Cong influence and subjected to brainwashing and surveillance with no freedom of movement. In January 1962 Operation Ranch Hand introduced herbal warfare including the use of Agent Orange. This aerial defoliation not only destroyed land and ecology but also led to cancers, birth defects and other long term health problems in Vietnam.

In April 1963 Kennedy cynically recorded: “We don’t have a prayer of staying in Vietnam. Those people hate us. They are going to throw our asses out of there at any point. But I can’t give up that territory to the Communists and get the American people to re-elect me.”

It was an abhorrent record and, although still a child in 1963 with only a hazy knowledge of the full horror of American foreign policy, I sensed something wrong in the sycophantic media coverage and the deferential tributes. Though unfamiliar with the concept of establishment propaganda, the constant repetition of the Camelot myth raised my suspicions, and the uncritical public effusions of distress seemed fabricated. So I was surprised when, years later, accompanying more worldly Politics Students on an annual trip to Washington, they invariably showed enthusiasm for crossing the Potomac to Arlington to see the Kennedy grave. Challenged, they proved themselves well informed as to the noxious nature of the Presidency yet remained susceptible to the contrived allure of the Camelot myth.

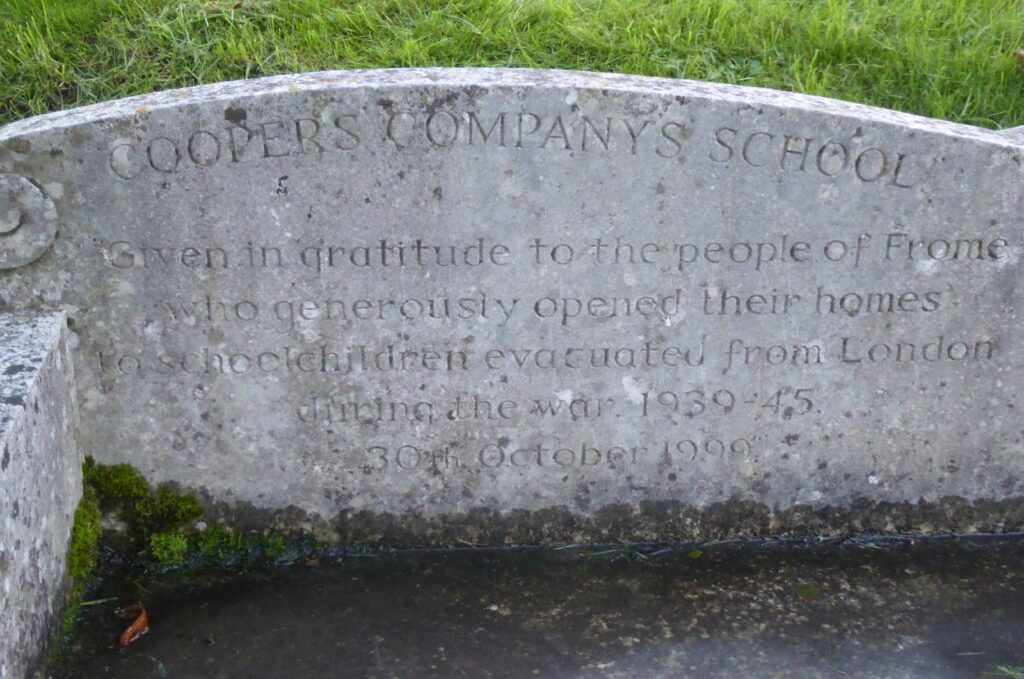

The second death on that November day was that of the academic and writer, CS Lewis (1898-1963). Amongst his sizeable output of fiction and nonfiction it is his children’s books The Chronicles of Narnia, seven fantasy novels which have sold over 120 million copies and been translated into forty-seven languages,for which he is best remembered. Like most small children I was once enchanted by the world of Narnia; what imaginative child would not be thrilled at the prospect of entering a large wardrobe full of fur coats to discover a secret exit at the back leading to a magical kingdom of ice and snow, mythical creatures, and talking animals. It is a cleverly woven story of wonder, mystery, and adventure. Lewis began to write it in the 1940s when children came to his house in Oxford as evacuees from London, and the four siblings who discover the world of Narnia were based on them.

But it did not take me long to realise that behind the richly imaginative narrative lay a manipulative allegory, a Christian subtext with the lion Aslan a Christ like figure sacrificing himself to torture, suffering and humiliation to redeem Edmund who has betrayed his siblings to the White Witch. Aslan’s sacrifice vanquishes death, and he returns to life but only the trusting and unquestioning Lucy can see him; the message at the heart of this proselytising text is the importance blind faith, obedience to an authoritarian moral system, and an acceptance that there are things one is “not meant to know.”

I may not share Philip Pullman’s view that this is “one of the most poisonous things I have ever read” but alongside the Christian propaganda aimed uncomfortably at young children, there is also a pernicious defence of established hierarchies and a tacit acceptance of violence. The racist disparagement of the Calormenes, and the unquestioning acceptance of class and gender stereotypes is disturbing. The female character of the White Witch, responsible for its being “always winter and never Christmas,” personifies evil, and when Susan becomes too interested in nylons, lipstick, clothes, and boys she can no longer return to Narnia. Worse, as Pullman says, is the terrible myth that death is better than life, the idealised view of an afterlife upholding a reactionary idealised theocracy.

But just as the Camelot myth drew my students to Kennedy’s grave, so the magic I remembered in his stories enticed me to that of CS Lewis. I did not have high expectations for the graveyard of a Victorian church, located in an old quarry in an Oxford suburb, but Holy Trinity churchyard in Headington is a delightful place. I visited on the eve of springtime as the soft green shoots of snowdrops and hellebores were emerging, and it resembled more a country churchyard than a suburban one. The gnarled roots of an ancient yew circle the honey-coloured stone marking the grave of Lewis and his brother which bears a quotation from King Lear.

Lewis’ mother had a calendar with quotations from Shakespeare, his father kept the leaf from the day she died, Lewis’ brother Warren had the quotation inscribed on the grave.

And I was reluctantly charmed by the Narnia window in the church

My third grave however houses someone who was aware and wary of the power of indoctrination and conditioning, the uncritical conformity which media myths and social engineering, fairy stories and brainwashing can engender.

Aldous Huxley (1894-1963), writer and philosopher, had published his most famous work the dystopian Brave New World in the early 1930s but it was still very popular when my school friends and I discovered it in the 60s. Eagerly we debated his vision of an establishment controlling a docile population through a combination of drugs and entertainment, maintaining economic and social divisions with neither alphas nor epsilons questioning their status but accepting a caste system, convinced that all was right with their world.

Paradoxically Huxley’s own experiments with mescalin recorded in The Doors of Perception (1954) led him to believe that the consciousness altering drug could also promote enlightenment, and that drug taking could be a legitimate expression of intellectual curiosity, removing inhibitions and increasing awareness. In the 1960s this chimed with a youth subculture seeking social change and experimenting with psychedelic drugs and the hallucinogenic power of LSD, and Jim Morrison’s rock group – The Doors – took their name from the title of Huxley’s book. (He in turn had taken it from the visionary poet and artist William Blake: “if the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.”)

Ostentatiously clutching our copies of The Doors of Perception was as close as we came in our provincial girls’ school to the drug subculture of the sixties. And if we perceived it then as a more glamorous world than our own and lauded Huxley for his avant-garde views yet when I reread his book recently I confess that I found it dull. Worse, it contradicted the scathing indictment of mindless acceptance and unquestioning obedience which he had wrought in Brave New World. Yet though this may have been disappointing, his grave was nonetheless the one which I approached with most respect for the memory of its occupant.

Huxley is buried in the Watts Cemetery, home of the Watts Mortuary Chapel, at Compton near Guildford in Surrey.

Alongside him are other members of his illustrious family including his father Leonard, biographer and editor.