This year marks the 200th anniversary of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution. It was founded in the London Tavern in Bishopsgate on 4 March 1824. At this time around 1,800 ships a year were wrecked on the coasts of Britain and Ireland. Under the aegis of the RNLI, lifeboat stations were strung around the coasts like jewels, but these were not gaudy, meretricious, coloured stones, but plain shelters housing sturdy boats ready to put to sea in the worst of conditions.

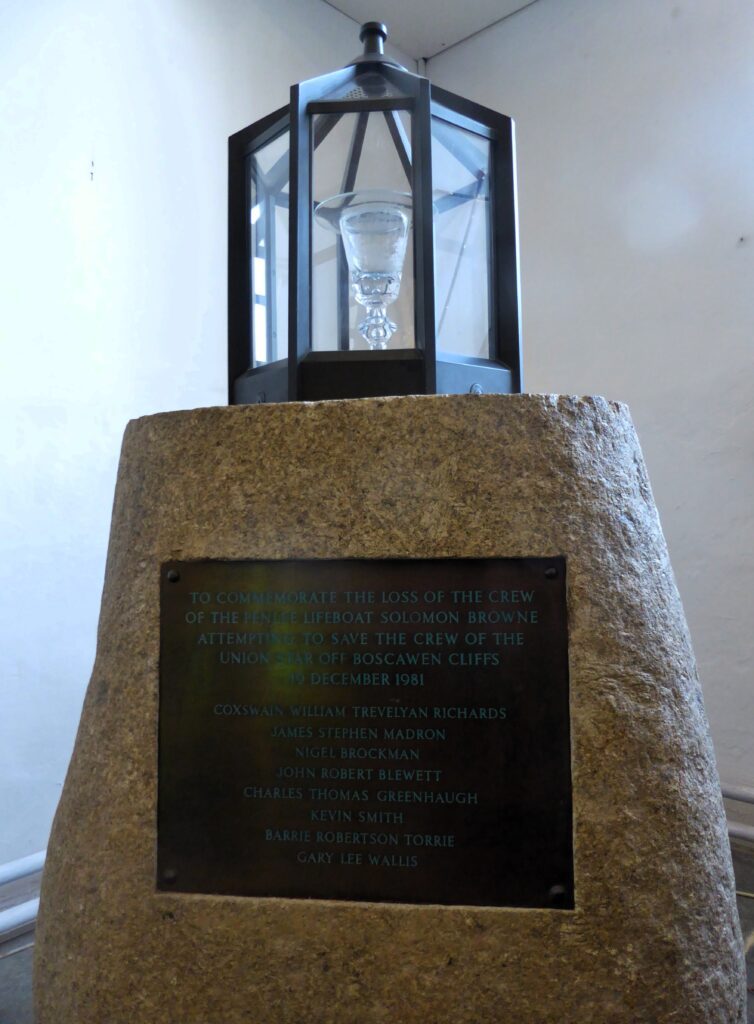

Their volunteer crews have saved nearly 150,000 lives, an average of two per day since its inception. But this comes at a cost and more than six hundred people have died in the service of the RNLI. Graves and memorials in coastal towns and villages bear witness to tragedies. One story stands for them all.

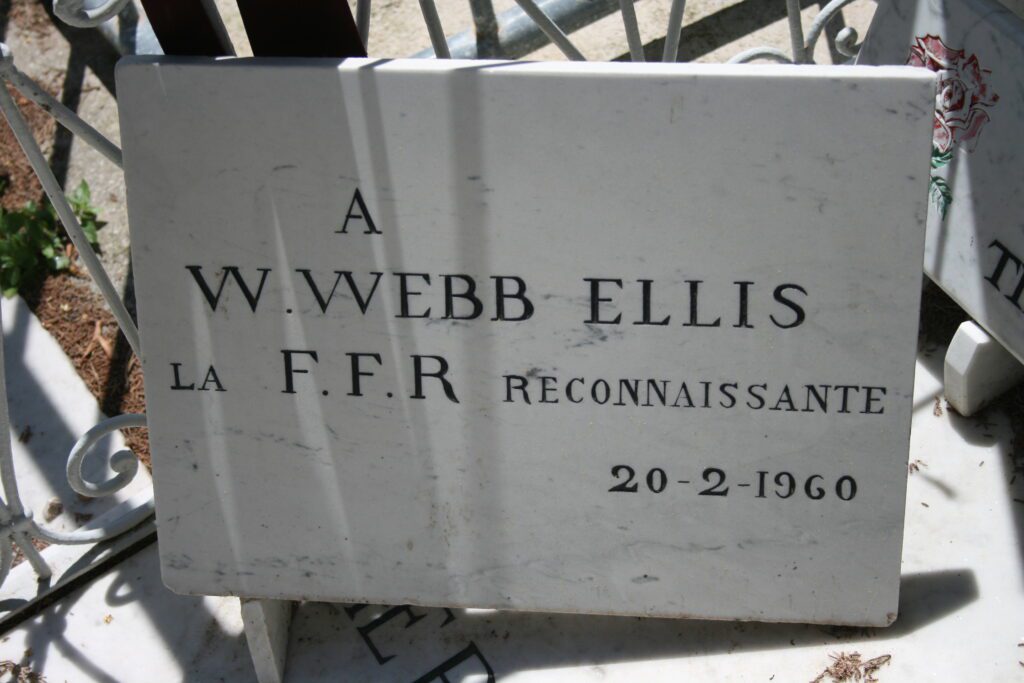

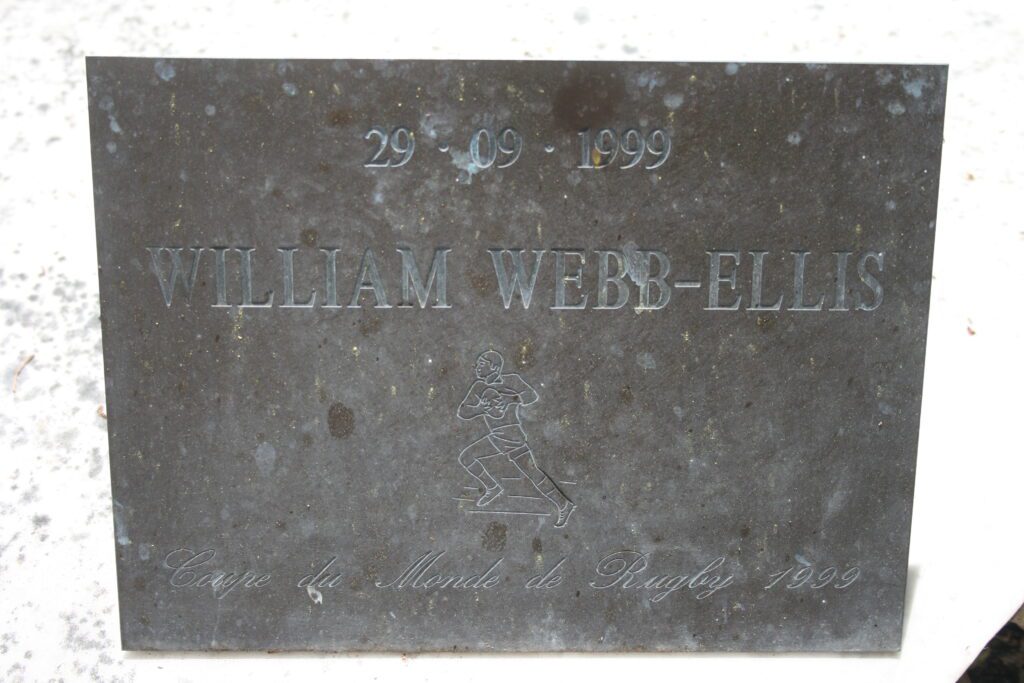

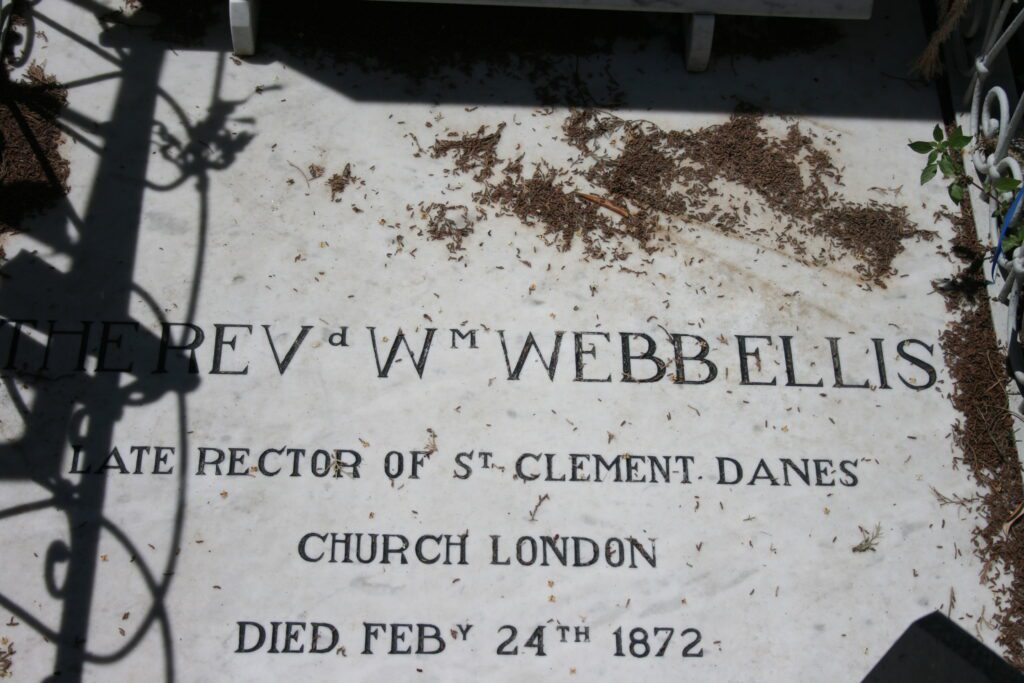

The historic fishing village of Mousehole in the southwest of Cornwall is a fairytale place. Huddled cottages of Lamorna granite tumble down to the perfect little harbour once home to the great pilchard fleets. There are seals swimming off the coast and a tidal pool for wild sea swimming. The summer brings holiday makers and in winter the Mousehole Harbour Lights draw crowds from early December to the first week of January. But every year on the 19 December the lights are dimmed in memory of the crew of the Penlee lifeboat, the Solomon Browne.

On the 19 December 1981, the Union Star was sailing from Holland to Ireland with a cargo of agricultural fertiliser. On board were the captain, four crew members, the captain’s wife and their two daughters. Around 6pm the ship’s engines failed, and the fuel system became contaminated with water. As rough seas and powerful winds blew the coaster towards the dangerous shore, she lost one of her anchors. The Penlee lifeboat launched in a hurricane, ploughing against ninety knot winds and 18m waves as it struggled to came alongside the coaster. Once in position, the crew of the Solomon Browne waited to catch people as they jumped for the lifeboat. They radioed to the coastguard that they had rescued four of the eight people, but as they made a final desperate attempt to save the others, radio contact was lost. Ten minutes later the lights of the Solomon Browne disappeared. In the morning wreck debris from both boats washed ashore. (“The 1981 Penlee Lifeboat Disaster – RNLI History”)

For all its charm and beauty there is a sadness about Mousehole as in all those towns and villages which have lost brave crews to the sea. The compassion and selfless courage which has led generations of volunteers, often from the same families, to risk their own lives to help others, inspires a measure of love and admiration for the RNLI which is seldom equalled by any other institution.

So, it was sickening when in 2021 Nigel Farage condemned the RNLI for rescuing asylum seekers trying to reach the UK in small boats, claiming that the lifeboats were providing “a taxi service” for illegal migrants. Influenced by his demagoguery and the moral panic about migration stirred up by the right-wing press, some members of the public verbally abused rescuers bringing people to safety, others tried to prevent the RNLI launching a rescue boat in Hastings just days before twenty-seven people drowned in the Channel.

Priti Patel, then Home Secretary, and sharing Farage’s views, introduced the Nationality and Borders Bill which sought not only to make it illegal for asylum seekers to enter the UK without permission, but also to make it a criminal offence “to facilitate the entry of asylum seekers” by taking them ashore – an offence which was to carry a maximum sentence of 14 years.

But reaction was swift. The RNLI released harrowing footage of a sea rescue and volunteers detailed the desperate state of asylum seekers in overcrowded boats at risk of drowning in the Channel.

The RNLI chief executive, Mark Dowie, said that the lifeboat service had always rescued whoever needed their help: “We were pulling German airmen out of the Channel in the Second World War.” The RNLI, he emphasised, exists to save lives at sea without judgment. They do not question why people get into trouble, do not ask who they are or where they are from.

Subsequently, the RNLI’s fund raising, with money coming from one off payments, new supporters, and increases in regular contributions, reached £200,000 in a single day, thirty times the usual average, and a record year of donations followed.

Some quirky fundraising campaigns ensued. Partly in jest, Simon Harris sought to raise money for a new RNLI hovercraft to be called the Flying Farage. Donations reached £238,130 of its target £250,000 this Easter weekend. Harris has made clear that the specific proposal was tongue in cheek and that all money raised will go directly to the RNLI to be spent at their discretion.

Recently the local shop owner on the island of Sanday in the Orkneys accidentally ordered eighty cases of Easter eggs instead of eighty eggs. He organised a raffle in aid of the RNLI to get rid of some of the 640 excess eggs. By Maundy Thursday this had raised over £3,000, and the food company producing the eggs has agreed to match the final total.

Meanwhile,under pressure, and with bad grace, the government accepted an amendment to the Nationality and Borders Bill in December 2021. The RNLI was exempted, if people’s lives were in danger, from laws criminalising anyone helping asylum seekers to enter the UK.