Once a beloved national institution, the General Post Office has fallen from grace.

The Cameron government severed the Post Office Ltd., controlling branch post offices, from the Royal Mail, responsible for the delivery of letters. It privatised the latter. After a rushed sale at which they were clearly undervalued, the price of its shares on the stock market rose by 38% on the first day of trading, by 70% within a year, and peaked at 87%. As the profits of shareholders rose, previously high levels of public satisfaction with the service plummeted.

Now there are proposals to dismantle the Universal Service Obligation under which letters are delivered six days a week to every address in the United Kingdom. Deliveries are likely to be reduced to five or even three days a week, and the target delivery time for all domestic mail reduced to a meaningless “three days or longer.” But to customers in many parts of the country these suggestions are the more risible for coming ex post facto, as the frequent absence of any deliveries for a week or more has already left a legacy of missed hospital appointments, useless postal votes, and financial difficulties. Journeys to sorting offices reveal bundles of missing mail accumulating there. Significantly stamp cancellations no longer show the date and time of posting.

None of which prevents anyone from loving their postmen and postwomen. The determination with which so many wear shorts even in the coldest weather is a source of amused affection. All but the most unpleasant and aggressive drivers will move out of the way for their red vans. In our village, where we do still get a six-day delivery, Nicky is known to everyone. When mail is too unwieldy for the letter box she will knock, when she knows that people are deaf or elderly, she will knock extra hard and wait until we open the door. When there is no response she leaves mail with neighbours. And if subsequently she spots us out in the lanes the red van will stop, and she will lean out to tell us where our post has gone today. But the job involves early starts, heavy loads, exposure to all weathers, and delivery rounds have become larger as management seek to squeeze more productivity out of employees. There are not enough post carriers to cover all rounds adequately.

A similar pall hangs over the Post Office Ltd. In the mid-sixties there were 25,000 branch post offices, by March 2021, there were only 11,415, and it is expected that thousands more will disappear in the next few years.

Moreover, an egregious miscarriage of justice has blighted the lives of thousands of sub postmasters. In 1999 a faulty computer software system, Horizon, was installed in branch post offices. It created false cash shortfalls. Sub postmasters called the Horizon helpline when these errors appeared on their screens and were led to believe that the problem occurred only at their own branch. Post Office executives persistently claimed that the Horizon system was robust. Between 1999 and 2015, 4,000 sub postmasters were accused of financial wrongdoing. They lost their jobs and were forced to repay the “losses,” many becoming bankrupt and losing their homes as a result. More than nine hundred of them were prosecuted for theft, false accounting, and fraud; seven hundred were convicted; over two hundred were sent to prison. Some pleaded guilty to avoid jail. Four people took their own lives. Chief executives at the post office continued to deny their knowledge of the faults in the system.

For twenty-five years, Alan Bates has led his fellow sub postmasters in a fight to clear their names. In 2017, 555 of them took legal action against the Post Office in the civil courts, and in 2019 a judge ruled that the software was defective, and in an out of court settlement, compensation, largely swallowed up by legal fees, was paid. This did however open the way for the sub postmasters to challenge their convictions and over a hundred have been quashed. In 2021 the government set up a Public Enquiry to investigate malpractice by the Post Office.

Recently a TV drama series, Mr. Bates vs. the Post Office, recounted these events. Since then, the government has announced plans for legislation to provide a blanket exoneration for all the wrongly convicted, and for the Post Office to pay compensation to all the victims of false accusations, but progress is slow. To date more than sixty people have died waiting for justice.

There had been a postal system of sorts in Britain since the seventeenth century, but it was only in 1840 that Rowland Hill introduced a uniform system with prepayment evidenced by the attachment of a Penny Black postage stamp. Previously the post had been mismanaged, expensive and slow, the rates complex. Payment had been made by the recipient who could refuse delivery. An apocryphal story suggests that Rowland Hill’s concern was aroused after seeing a young woman too poor to claim the letter sent by her fiancée. Hill’s system was speedy, cheap, and dependable. The number of letters sent doubled in the first year and the increase in volume continued. By the late nineteenth century London had between six and twelve mail deliveries per day. Elsewhere there were four deliveries. It was possible to post in the morning and receive a reply by evening.

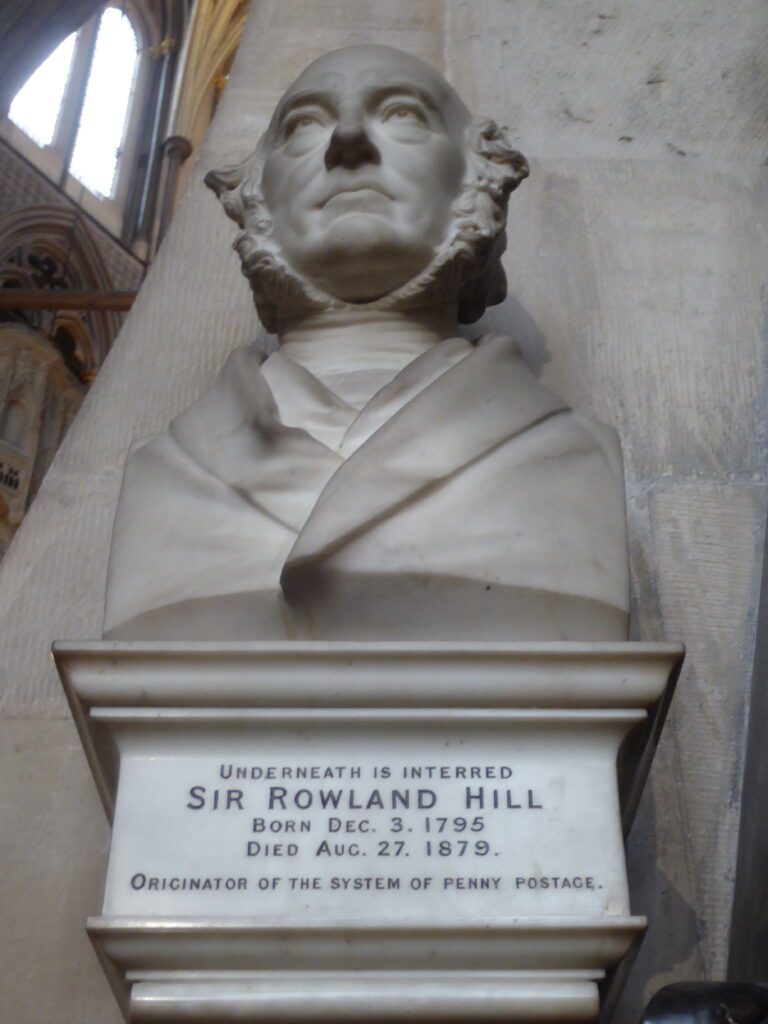

The name of Rowland Hill is forever associated with the post, and he is commemorated by statues in Kidderminster, Birmingham, and London, and, the ultimate accolade, a burial in Westminster Abbey. The Abbey is a magnificent building but within lies a mess of centuries of haphazard graves and memorials treading on each other’s toes as they vie for space. Nonetheless Rowland Hill secured both a memorial and grave. In 1879 his was the last arrival amongst the distinctly crowded and overwrought tombs in St. Paul’s Chapel. His bust peers down at a modest stone marker set into the floor.

Today Anthony Trollope’s fame rests on his novels. But much of his prolific output was composed on horseback, or later at a portable desk on the train, as he travelled the country in his capacity a postal surveyor’s clerk. The result was forty-seven novels. Perhaps reflecting the circumstances in which he wrote, and his reluctance to revise anything, they tend to the long and repetitious, but he produced some gems. I am particularly fond of the Ointment Heiress; her title alone is a delight. I imagine the eponymous ointment to be germolene pink and contained in a tight little metal tin bearing extravagant claims. Moreover, Martha Dunstable is one of the few nineteenth century heroines who can command respect, being worldly, witty, and sensitive unlike the simpering paragons and grasping harridans generally beloved of Victorian novelists. *

But Trollope also gave us our red pillar boxes. Sent to mainland Europe to observe their postal schemes, he admired the cast iron letter receiving pillars in France and Belgium. In 1854 at his recommendation the first pillar box was introduced in Britain, obviating the need for a trip to the post office. Originally painted sage green, the boxes turned red in 1874. ** As they reached the height of their popularity in the 1860s and 70s, it is said that he regretted their adoption as it enabled young women to correspond with men in secret avoiding visits to the post office.

Trollope’s grave lies in Kensal Green, the first of the London Big Seven to open its doors to customers. The conventional stone disappointingly bears no reference to his writing nor to his association with pillar boxes.

In memory of

Anthony Trollope

Born 24 April 1815 Died 6 December 1882

He was a loving husband, a loving father,

And a true friend

More controversial are the claims of James Chalmers, bookseller, printer, and inventor. I found him in the Howff Cemetery in Dundee, where amongst the darkened stones his stood out on account of a newer, lighter stone directly in front of it. Placed my Chalmers’ son, the second marker makes no concession to modesty, describing his father as the

Originator of the adhesive postage stamp

Which saved the penny postage scheme of 1840

From collapse

Rendering it an unqualified success

And which has since been adopted

Throughout the postal systems of the World

I love the idea of anyone sitting down to invent an adhesive stamp, and the extravagant claim that without it the whole postage system would have collapsed, but the truth is more prosaic. Adhesive stamps had long been used on documents to show payment of taxes. Moreover, while Chalmers was certainly an enthusiast for postal reform, the earliest proposal found in his archives for an adhesive stamp or slip to send a letter is in 1838. In 1837 Rowland Hill had already written a pamphlet proposing not only the single rate of postage but also the use of stamps “covered at the back with a glutinous wash.” The descendants of Chalmers continue to produce pamphlets and articles claiming him as the originator of “stamp gum” but the claim seems tenuous.

I grew up an enthusiastic letter writer: penfriends in school days, letters home and to former classmates in university days, love letters, and, as university friends scattered around the world, letters bearing exotic stamps would arrive from Papua-New Guinea, Australia, New Zealand, America. No other form of communication can elicit the same joy as a letter: for someone has taken the trouble to gather pen, paper, envelopes, and stamps; to handwrite several sheets; to address their envelope; to lick their stamp;*** and to deliver the aesthetically pleasing stamped and sealed result to a post box.

But letter writing is in rapid decline. The volume of letters which the post office handles is down from twenty billion in 2011 to seven billion today, and most of those are invoices, business letters, advertising. In 2004 the second daily delivery was officially scrapped, but few of us recall receiving a second post that recently. At first, as friends embraced innovative technology, I held to my pen. Typed epistles would arrive as email attachments with requests to my partner to print them out as, “I don’t suppose she’ll deign to read it otherwise.” At work, younger colleagues watched with amusement as holding onto a pen like a comfort blanket with one hand, I stabbed crossly at computer keys with the other. But I succumbed at length: email is instant, photos easily attached, replies immediate, as many mails as you like in a day. And there is WhatsApp, Facebook and Twitter, Skype and Zoom; so much immediate, cheap communication. And yet, it carries little of the romance of a letter.

O Rowland Hill, Anthony Trollope, James Chalmers, the world has changed, your lovely post offices are disappearing, soon our post-boxes may join our K6 telephone kiosks as museum pieces. And the end now looks to be a bitter one, with a once noble organisation torn apart and all sacrificed to shareholders’ profits and CEO’s bonuses, but I treasure the memory of your Post Office in its happier days.

*Martha Dunstable appears in Dr. Thorne and in Framley Parsonage, both in The Chronicles of Barsetshire.

**In the 1930s blue post-boxes were introduced for airmail letters but were phased out again from 1939. One survives in Windsor.

***or to wet it with one of those sponges which used to appear in little round dishes in the post office. Self adhesive stamps appeared in America in 1974 but were not introduced in Britain until 1993.