In the early days of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution there were no women crews, not least because of the widely held suspicion that it was bad luck to have women crewing boats. But women always provided support, working to get the lifeboats afloat, and after an anxious wait recovering them from the water and readying them for the next launch. The women who lived along the coasts knew the dangers of the sea.

Grace Darling was the daughter of a lighthouse keeper on Longstone Island, one of the Farne Islands off the coast of Northumberland. On the night of 6 September 1838, the merchant ship the Forfarshire was carrying sixty-two people, crew and passengers, from Hull to Dundee. When its boilers failed the captain stopped the engine, and in a storm the boat drifted and foundered on the rocky island of Big Harcar. Almost immediately the ship broke in half and one half sank. In the early hours of the morning Grace spotted the wreck and survivors on the rock.

Believing that the weather was too rough for the lifeboat to be able to put out from the mainland at Seahouses, Grace and her father took a wooden rowing boat, a four-man Northumberland cobble, along the leeside of the islands, rowing over a mile through gale force winds and a churning sea. While her father clambered onto the rock to help the survivors on board Grace held the cobble steady, rowing backwards and forwards to prevent it being smashed on the reef. Then they made the slow, punishing journey back to the lighthouse.

The lifeboat had set out from Seahouses, Grace’s brother William Brooks Darling, a fisherman, one of the crew. Arriving after Grace and her father had rescued the nine survivors, they found only the bodies of two young children and an adult who had died of exposure.

So severe was the weather that the lifeboat crew too returned to the lighthouse. There everyone was obliged to remain for three days before it was safe to return to shore.

The Victorians were prone to hero worship although the cynosures of their admiration were usually pugnacious men expanding the empire and building colonies. Women generally found favour only in a passive role as “the Angel in the House,” but Grace’s courage and strength captured the popular imagination, helped no doubt by the fact that the shy, retiring, and modest young woman did not disturb the gender stereotype of women as caregivers.

Grace became a national celebrity, by all accounts uncomfortable in the role, finding herself expected to sit for portraits and feeling obliged to answer the tsunami of letters requesting locks of her hair or scraps of material from her dress. There were also the thank you letters to write in response to the strange gifts proffered by her admirers: the Duke of Northumberland sent a silver teapot, surely of little use in the lighthouse. Boats were even hired locally to take the curious out to Longstone Island to look at her.

Four years later, having contracted tuberculosis, Grace died at the age of only twenty-six, in the place of her birth, her grandparents’ cottage in Bamburgh on the mainland. The unwelcome adulation, or exploitation, continued: soaps, chocolate bars and a rose were named after her. Wordsworth, then Poet Laureate, wrote a tribute; Grace Darling is not one of his finer works.

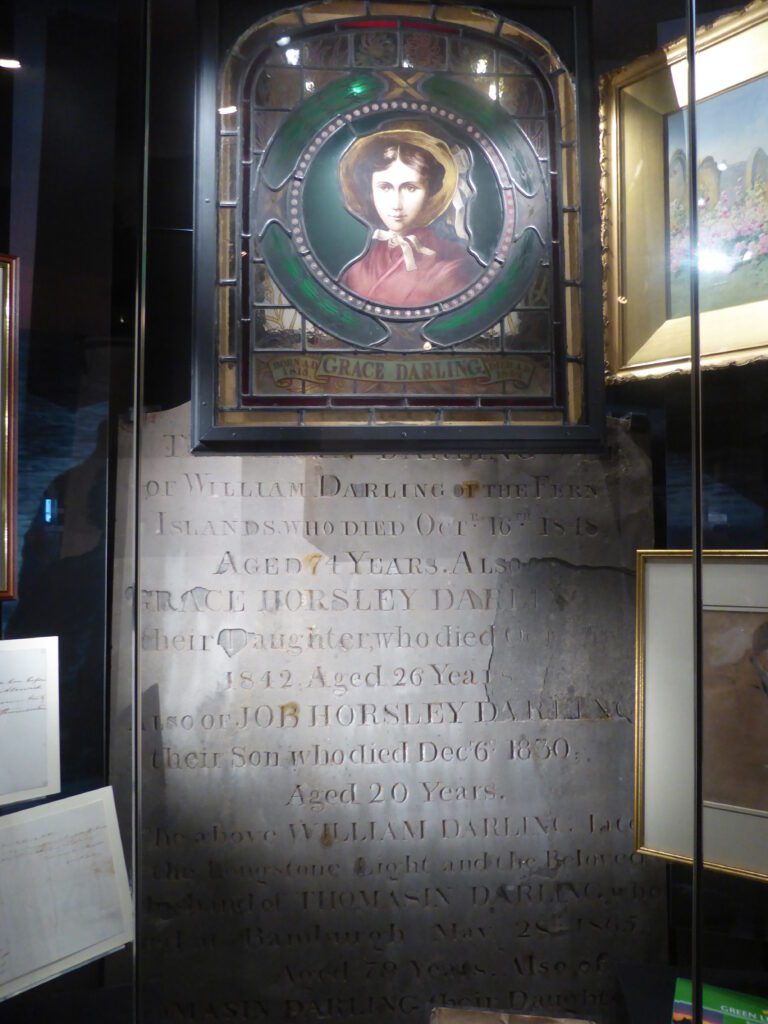

Grace is buried in St Aidan’s churchyard in Bamburgh, in the family grave. A few yards from the grave an elaborate canopied Victorian funerary monument was erected with a life size stone effigy of Grace holding an oar. Made of Portland Stone it quickly became weathered and was replaced as early as 1885 when the original was moved into the church. There she lies beneath a memorial stained-glass window. In the latter, again clutching an oar, she symbolises Fortitude, an unlikely tall figure with an abundance of blond hair: Grace was small and dark. She is flanked by Charity holding a heart and Hope with an anchor.

Charity Fortitude Hope

Grace Horsley Darling Born 24 November 1815 Died 20 October 1842

The Wreck of the Forfarshire 7 September 1838

After visiting the church and the graveyard, I crossed the road to the Grace Darling Museum established in 1938, passing her birthplace identified by a plaque. In the museum I viewed, amongst other things: the cobble; clothing which had belonged to Grace; her locket; and an account of her story in Japanese. Here too was the original family gravestone, for this had also weathered and been replaced.

I was beginning to feel that the small village of Bamburgh was overdoing it a little, in danger of reducing itself, and Grace, to a theme park. Then a party of primary school children entered the museum, buoyed up on a wave of seamless chatter, fingers and noses pressed to the glass display cases. Finally seated on the floor, barely fidgeting and almost silent under the eye of their teacher, they waited for the museum guide to speak to them. She told them the familiar story of Grace Darling’s bravery; it was a new story to them, but local children, they knew the temper of the sea on their coast and the dangerous rocky islands which pierce it, and they grew quiet and round-eyed.

The RNLI maintains the museum believing that the values of charity and concern for others which lie at the heart of Grace’s story, are mirrored in the selfless altruism which motivates lifeboat crews today, and they hope through telling the story to inspire others to support their work.

Bamburgh is no theme park. It is an ordinary village, albeit huddled beside an extraordinary castle, located on a spectacularly beautiful part of the Northumberland coast. But for all its beauty the sea can be cruel and capricious, and Bamburgh has a very special story to tell about a very brave woman who epitomised the fortitude, tenacity, and generosity of spirit which has inspired RNLI crews for two hundred years.