Red-Letter Days marked on the calendar commemorate religious and royal anniversaries. They do not resonate with me, but in their stead, I measure the year through secular and socialist festivals. This, the third weekend in July brings the Tolpuddle Festival, celebrating Trades Unionism and remembering the Tolpuddle Martyrs.

Rural poverty was endemic in nineteenth century England. Between 1770 and 1830 landowners annexed the common land on which villagers had grazed their animals and the plots where they had grown vegetables. The Enclosures brought wealth to those who owned the land and hardship to those who worked it. The latter became casual labourers, a precarious existence where they were hired and fired by the day or the week with no guarantee of work.Their impoverishment was exacerbated after 1815 when the rural labour market was swamped by soldiers returning from the Napoleonic Wars, enabling employers to keep wages low while raising rents. Alongside this the mechanisation of farming, particularly the advent of the threshing machine, increased unemployment, facilitating further wage cuts, and bringing farm labourers to the brink of starvation. In 1830 wages of only nine shillings a week had left agricultural workers struggling to survive on a diet of tea, bread, and potatoes. Yet year by year these wages were successively reduced to eight shillings, to seven shillings, and in 1834 to six shillings.

In southern and eastern England desperate men organised the Swing Riots, destroying threshing machines, firing hayricks, and damaging property, in a bid to pressure employers into improving wages. But the riots were put down by the militia, and executions, transportation, and prison sentences meted out.

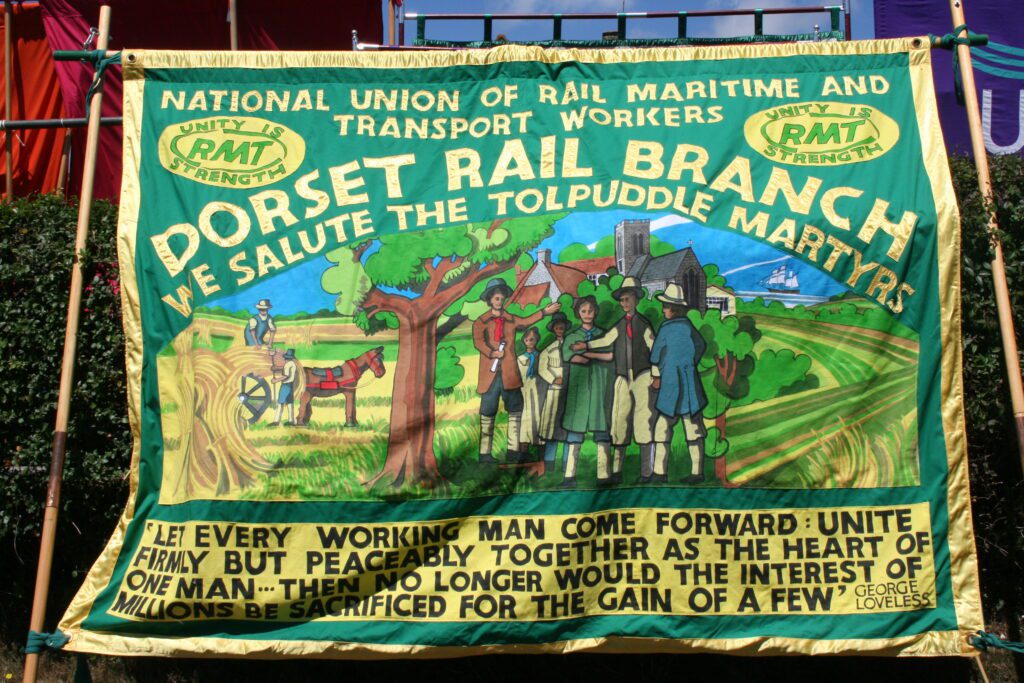

Against this background in 1833 six men gathered under a sycamore tree on the village green in Tolpuddle. George Loveless, James Loveless, James Hammett, Thomas Standfield, John Standfield, and James Brine founded the Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers, a benefit society and self-help group seeking to improve their conditions and reverse the wage cuts without resort to violence. Already rattled by the Swing Riots and made nervous by the French Revolutions the reaction of their employers, supported by the government, was swift. The six men were arrested on 24th February 1834, tried at the Dorchester Assizes in March, and sentenced to seven years transportation to Australia. The Home Secretary, Melbourne, wrote with satisfaction to the king that this would strike a mortal bow at the root of Unions.

There were no legitimate grounds for the trial and punishment. Trade Unions were by this time legal; the Combination Acts had been repealed in 1824. A spurious argument that the men had administered an illegal oath of allegiance as part of their ritual initiation was the basis of the sentence. Part of the preamble to an Act of 1797, which designated the swearing of oaths of allegiance to anyone other than the king as treason, was invoked to establish their guilt. But this Act had been specifically designed to prevent mutiny by sailors press-ganged into the navy. Outside the navy the swearing of oaths remained widespread in societies, charitable organisations, and clubs of all kinds, confirming new members, and establishing contracts where standards of literacy were low. Certainly, the government never questioned this practice when employed by Free Masons or the Orange Order.

At the end of their trial George Loveless voiced the men’s defence: “We have injured no man’s reputation, character, person, or property. We were uniting together to preserve ourselves, our wives, and our children, from utter degradation and starvation.”

As they left the court following the conviction Loveless threw a paper into the crowd bearing verses he had composed, The Song of Freedom:

God is our guide! From field from wave,

From plough, from anvil and from loom,

We come, our country’s rights to save,

And speak the tyrant’s faction doom:

We raise the watchword “Liberty”

We will, we will, we will be free!

God is our guide! No swords we draw,

We kindle not war’s battle fires,

By reason, union, justice, law,

We claim the birthright of our sires;

We raise the watchword “Liberty”

We will, we will, we will be free.

In chains the men were transported in hulks to Botany Bay as convict labour for landowners there.

Almost immediately Robert Owen instigated a meeting of the General National Consolidated Trade Union, and a national protest attended by 200,000 people was organised in London. Melbourne responded by turning out the Lifeguards, Household Troops, detachments of the 12th and 17th Lancers, two troops of the second dragoons, eight battalions of infantry, twenty-nine pieces of ordnance and cannon, and 5,000 special constables. He found no excuse to use them as the peaceful march proceeded in absolute silence from King’s Cross to Whitehall, to the Elephant and Castle and on to Kennington Common. The marchers presented a petition bearing 800,000 signatures requesting a pardon for the Tolpuddle men. Melbourne refused to accept it. But in Parliament William Cobbett and Joseph Hume continued to exert pressure and eventually the new Home Secretary John Russell recognised the force of feeling and persuaded the king that it would be wise to grant a pardon.

After their return to England in 1837 five of the men moved first to farms in Essex where they organised a Chartist association leading the local squirearchy to alert the Home Office to the fact that they were “still dabbling in the dirty waters of radicalism.” Later they emigrated to Canada with their families.

Only James Hammett remained in Tolpuddle where he became a builder’s labourer. As a new agricultural depression swept the country in the 1870s villages like Tolpuddle lost between a quarter and a third of their population as their inhabitants chased work in the industrial Midlands and the North, in Canada and Australia. Men continued to be sacked and evicted if they joined unions. Dying in the Dorchester workhouse in 1891, Hammett was buried in the churchyard of St. John the Evangelist in Tolpuddle. It was stipulated that there should be no speeches at the graveside.

The Trades Union Congress began to organise annual gatherings at Tolpuddle in the 1930s, and in 1934, on the anniversary of the arrests, erected a gravestone carved by Eric Gill and unveiled by George Lansbury. Six memorial cottages and a library were built for retired agricultural workers, the cost born by the unions paying a farthing per member for two years.

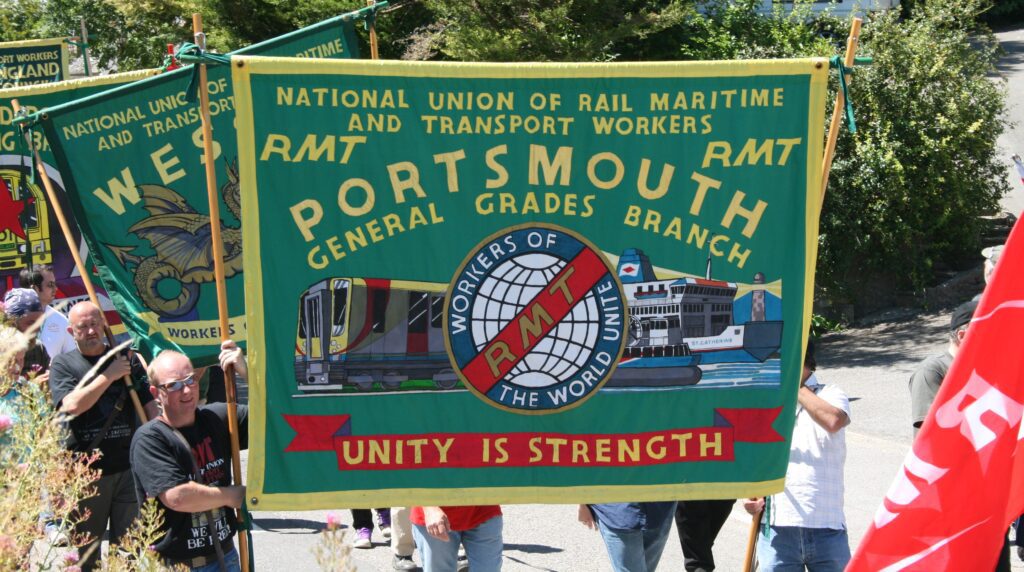

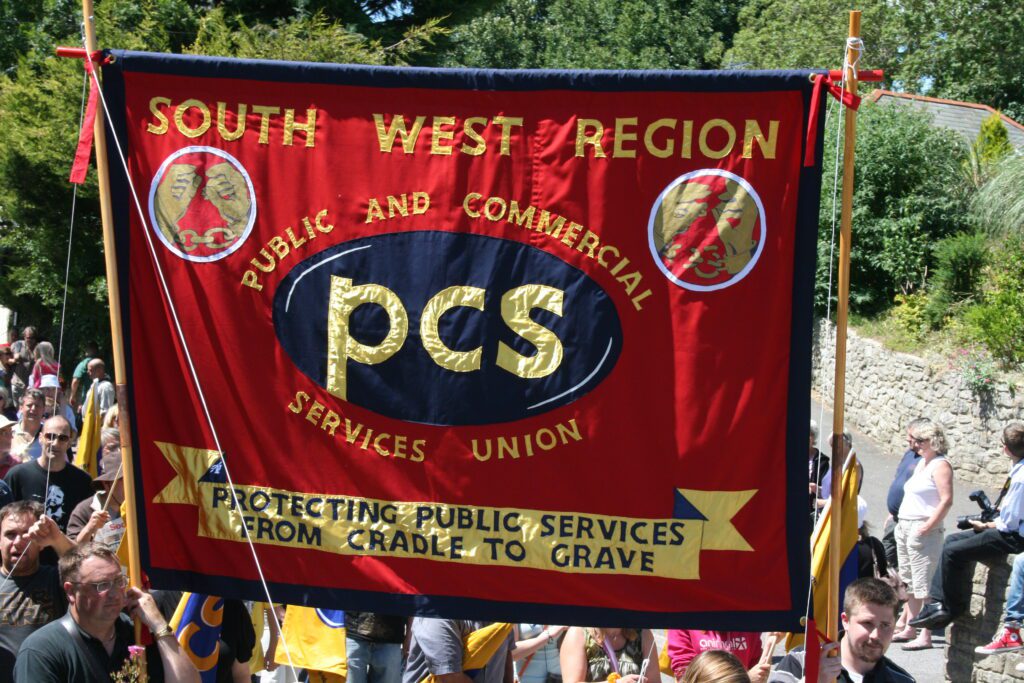

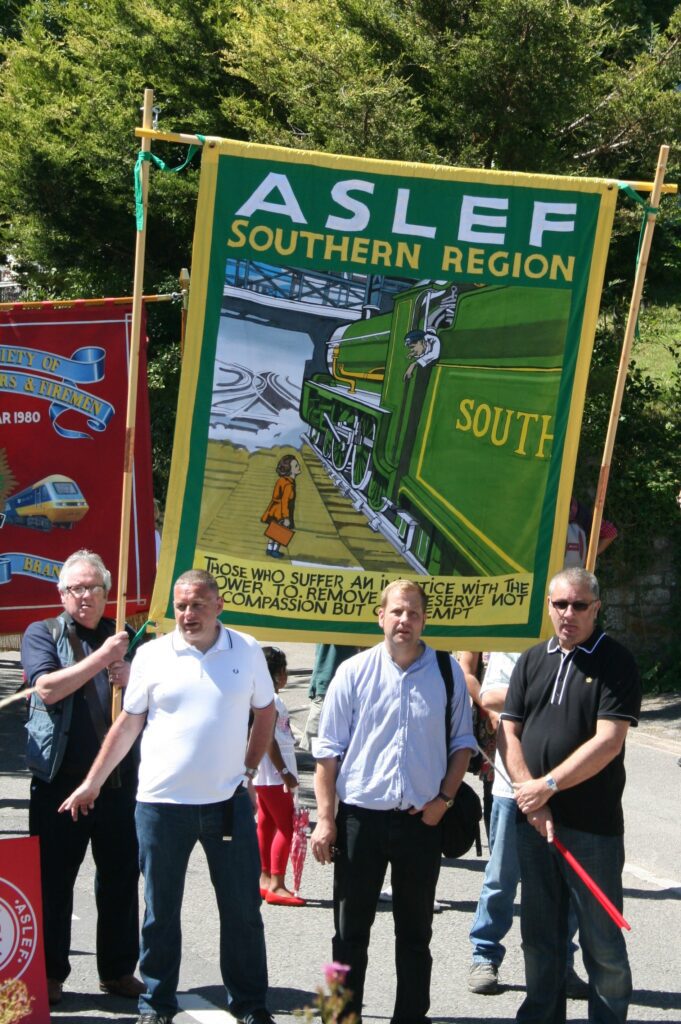

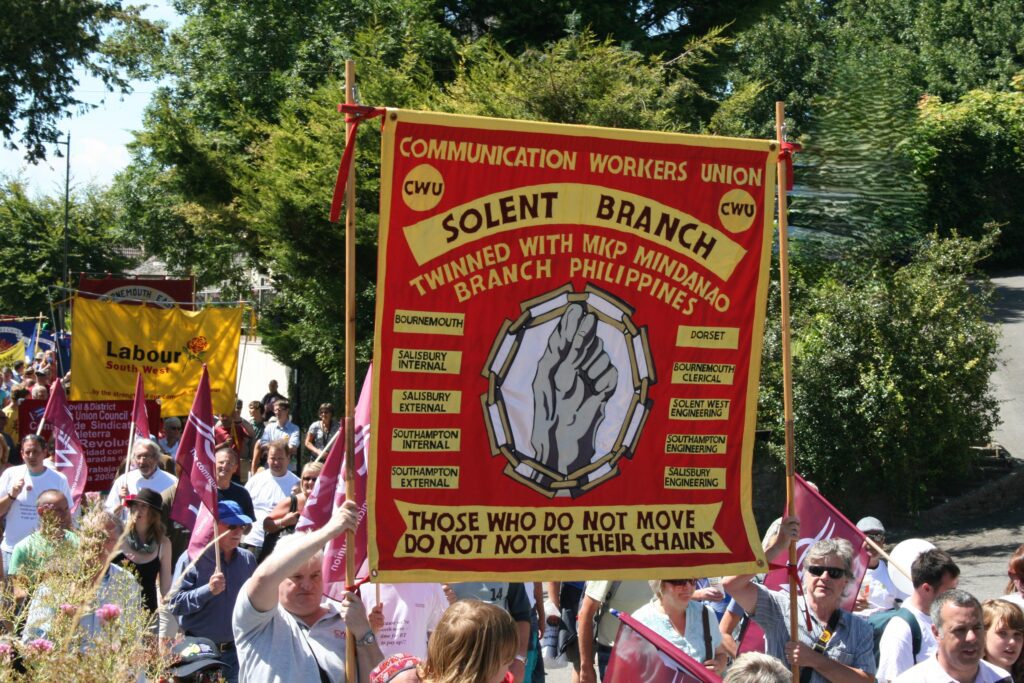

Since 1998 the TUC has held a festival alongside the rally, and today thousands gather from Friday to Sunday in the tiny Dorset village. But this is no commercial Glastonbury with extortionate prices and dubious sanitation. Entry fees for Friday and Saturday are deliberately kept low to ensure that the festival is accessible to all, no profit is made, and any deficit is covered by the TUC. Entry on Sunday is free. There is music, of course, but also drama, artists, talks, discussions, lectures, debates, stalls of socialist literature,and rousing speeches from Union leaders and sympathetic MPs. There is beer in the pub and tea and cake in the village hall. In 2015 the first Tolpuddle wedding took place, the couple surrounded by union banners and photographed under the martyrs’ tree. But the high point is always on Sunday afternoon when the unions process along the village street with banners and brass bands, and lay wreaths at the grave of James Hammett remembering the role that he and the other martyrs played in the long struggle for fair wages, freedom of association, justice, and liberty.