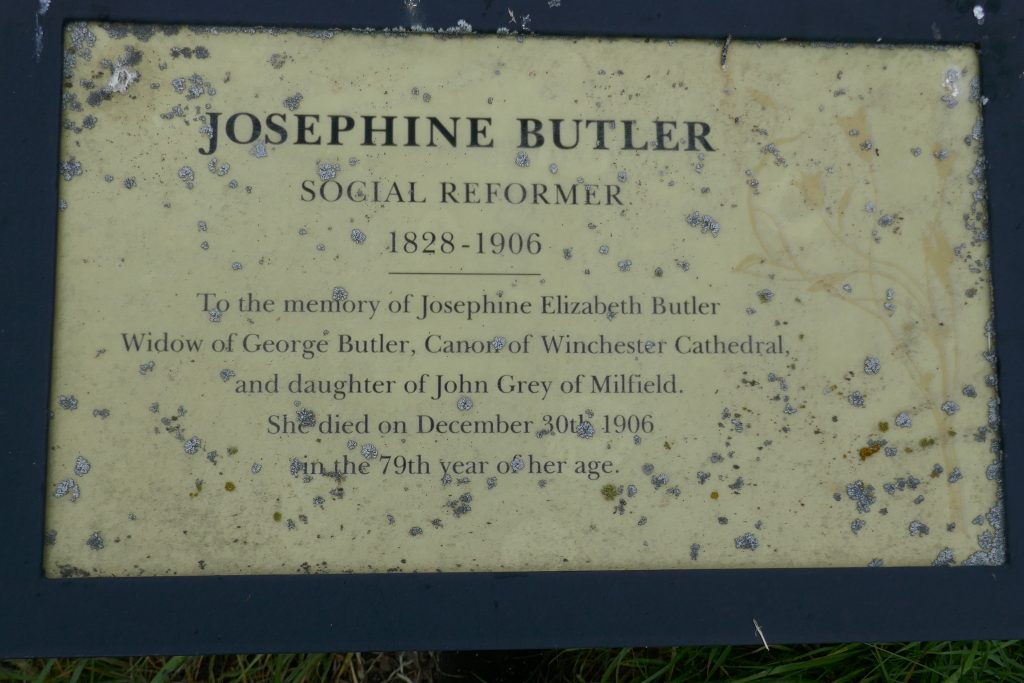

My admiration for the work of Josephine Butler (1829-1906) is tempered by an uncomfortable aversion to the religious beliefs which kindled and stoked her extraordinary achievements.

Butler grew up in a conventional, albeit liberal, middle-class family with strong religious principles, political connections, and social awareness. Her father was an active supporter of Catholic emancipation, the abolition of slavery, the repeal of the Corn Laws, and reform of the Poor Law.

But, at the age of seventeen, the then Josephine Grey had a religious crisis; becoming disenchanted with the Anglican church she began speaking directly to god in prayer, an intimacy which became the basis of her life and vocation. And this is where, as an atheist, I begin to feel a little uneasy: for a Victorian lady conformity to the social norms of church attendance is unsurprising but developing a hotline to god is disturbing.

When in 1852 she married George Butler, an academic and Anglican clergyman, she wrote that they often

prayed together that a holy revolution might come about and that the Kingdom of God might be established on the earth.

Although offended by her husband’s fellow dons speaking of

a moral lapse in a woman…as an immensely worse thing than in a man

she chose not to voice her views on the subject but

to speak little with men, but much with god.

Yet after the death of her daughter Eva, and her own problems with depression, she

became possessed with an irresistible urge to go forth and find some keener pain than my own, to meet with people more unhappy than myself.

Since the Butlers had now moved to Liverpool this was not difficult, and her activities immediately surpassed the conventional charitable works expected of clergy wives: she began visiting the workhouse where she sat in the cellars, picking oakum with the women while discussing the bible and praying; she established a hostel for women who had been seduced and abandoned, and helped them to find work; she offered shelter in her own house to prostitutes in the terminal stages of venereal disease.

But it was in 1869 that Butler’s most innovative work began. The Contagious Disease Acts of 1864, 1866 and 1869 sought to reduce the prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases, particularly in the army and navy, by maintaining a supply of uninfected prostitutes. To this end the police were authorised to detain any women who were suspected of prostitution – no evidence was needed. Any unattended woman from the age of twelve could be apprehended. Police powers were frequently misused against women whose only crime was poverty.

The women were then subjected to an invasive medical examination, which Butler described as “surgical rape.” If they were found to have venereal diseases they were sent to a lock hospital, one of the old leper hospitals, called after the locks or rags which covered the lepers’ lesions. Incarcerated in these institutions, more like prisons than hospitals, the women had no means to support their children and were unlikely to obtain employment on release. If women refused the examination, they were subjected to a three-month prison sentence or hard labour.

There was no enforced examination of their male clients who were exonerated from any responsibility. The Acts, as Butler made clear, were there to protect male health rather than to eliminate venereal diseases.

Butler established The Ladies National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Act, the first politically focused campaign organised and led by women. She toured Britain, speaking at scores of meetings, arguing that the Acts were discriminatory on grounds of both sex and class for they

not only deprived poor women of their constitutional rights and forced them to submit to a degrading internal examination, but they officially sanctioned a double standard of sexual morality, which justified male sexual access to a class of “fallen” women and penalised women for engaging in the same vice with men.

No surprise that Butler met with opposition from pimps, brothel keepers, clergy, and politicians. At one meeting cow dung was thrown at her, at another the windows of her hotel were smashed, at a third threats were made to burn down the building. She was disowned by friends and acquaintances, for it was not acceptable for a respectable woman to speak publicly on sex and prostitution. There were personal attacks by journalists and MPs. The London Daily News thundered

Women like Mrs. Butler are so discontented in their own homes that they have to find an outlet somewhere… and take pleasure in a hobby too nasty to mention.

For James Elphinstone MP, Josephine Butler was

worse than a prostitute.

Another newspaper vilified her as

an indecent maenad, a shrieking sister, frenzied, unsexed, and utterly without shame.

And a Royal Commission set up in 1871 defended the one-sided nature of the legislation:

There is no comparison to be made between prostitutes and the men who consort with them. With the one side the offence is committed as a matter of gain; with the other it is an irregular indulgence of a natural impulse.

The statement could not have substantiated more palpably Josephine Butler’s accusation of double standards.

It was not until 1886 that the noxious Acts were formally repealed, largely because of her relentless campaign. As one MP told her,

We know how to manage any other opposition in the House or country, but this is very awkward for us, this revolt of women.

Meanwhile Butler had toured France, Italy and Switzerland meeting women conducting similar campaigns. There she had become aware of the “white slave trade,” of girls as young as twelve being kidnapped or bought, and trafficked from England to the Continent, where they were sold as prostitutes. Alongside Florence Soper Booth and William Stead she became involved in her second great campaign, to expose child prostitution and the associated trade.

To publicise their cause Stead famously purchased a thirteen-year-old girl, Eliza Armstrong, from her mother for £5 and took her to a safe house in Paris. He then published a series of articles describing what he had done and exposing the extent of child prostitution. Butler followed this with speeches in London calling for greater protection of the young and the raising of the age of consent. Ironically both Butler and Stead faced police questioning following this audacious testimony and Stead was charged with abduction and imprisoned for three months.

Nonetheless in 1885 the age of consent was raised to sixteen and the procurement of girls for prostitution by drugs, intimidation, fraud, or abduction made a criminal offence.

Butler had traditional views on the importance of chastity for both men and women although this was informed as much by the lack of birth control and the risks of childbirth, as by a moral stand. Moreover, in the aftermath of the reforms of 1885 and 1886 she spoke out against the purity societies like the White Cross Army who sought to increase the prosecutions of brothel keepers and ban indecent literature… including information on birth control. She derided

the fatuous belief that you can oblige human beings to be moral by force,

and sounded a warning:

beware of purity societies…stamping on vulnerable women.

Knowing that women with no income and nothing else to sell would sell themselves she joined the fight for the training, higher education, and access to a wider range of jobs for women. She was instrumental in setting up the Married Women’s Property Committee which successfully pressured Parliament to get rid of the legal doctrine of coverture whereby when a woman married her property passed to her husband.

It is impossible to overestimate the achievements of Josephine Butler. Her work to eliminate sexual double standards, child prostitution, and the white slave trade, complementing the battles for the vote, education, and employment opportunities, brought not just concrete economic, political, and legal change, but was a precursor of the second wave of feminism, attacking the invisible power structures rooted in attitudes and prejudices.

She displayed enormous courage in addressing such unpopular causes. It is invidious to make a comparison, but if the suffragists encountered opprobrium for being so unfeminine as to demand the vote, how much more was Josephine Butler denigrated for daring to discuss prostitution and contagious diseases in polite society.

So how can I have any reservations about this woman? It is the religion. The social historian Sarah Williams argues convincingly that religious faith and spirituality grounded Butler’s activism and that her radical sense of justice was informed by her inner life of prayer. Suffering drove her grief for others, prayer was the basis of her vocation, and a part of her action to transform society. Similarly Judith Walkowitz considers Butler’s biography of Catherine of Siena (1878) an “historical justification for her political activism.”

The mystic Catherine of Siena, allegedly worked among the sick and the poor, helped bring peace to the Republics of Italy and encouraged the return of the Papacy from Avignon. Catherine’s reported lifestyle however is frankly creepy: it involved rigorous fasting, at one time an attempt to survive on the Eucharist alone; giving away other people’s possessions; drinking pus to overcome her disgust at the sight of patients’ sores; and having visitations from Jesus inviting her to drink his blood, and more… let’s not go there. She is hardly a great advertisement for political action informed by religious belief.

And the difficulty with anyone who believes that they have a direct line to any omnipotent god lies in the danger of their beliefs being a matter of faith, convictions not open to question or reason. This may not be a problem when they are doing good, but Josephine Butler’s beliefs were not always sound. There was her arrogant assumption that Britain had a mission to make converts to Christianity across the globe, and her endorsement of British Imperialism:

looked at from god’s point of view England is the best, and the least guilty, of the nations.

This led her to a position of apologist for British action in the Second Boer War. She did not acknowledge an abhorrent battle over the Witwatersrand gold mines, to which neither Boers nor British had any legitimate claim. Instead, she bought into the jingoism which claimed that the Boers were not fit to govern, and that the British were protecting the native South Africans. Her claim that British military manoeuvres were the “work of the holy spirit,” is the more repellent in the light of the British concentration camps where 100,000 Boer civilians, mostly women and children, were kept in appalling conditions, and where 26,000 died.

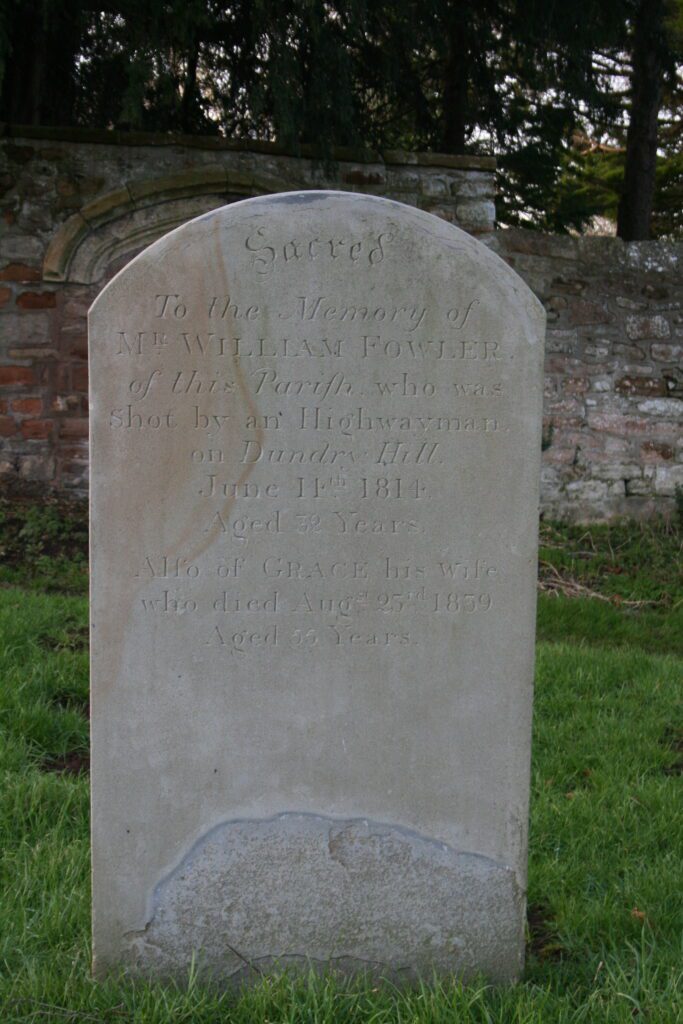

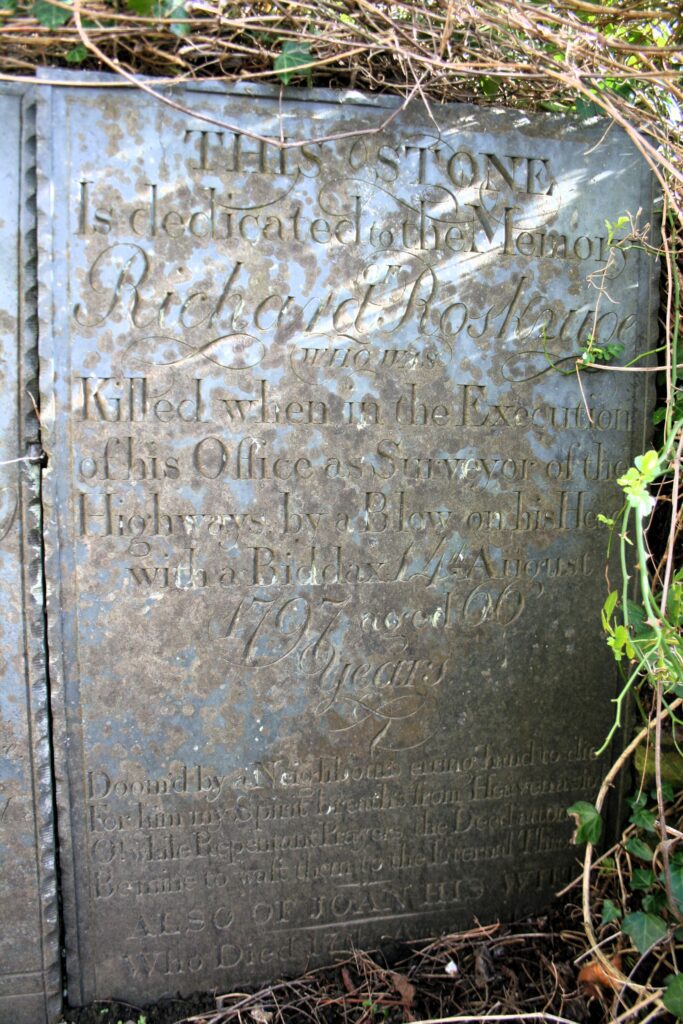

Yet though, like everyone, she may be a flawed personality, and I may be alienated by her dogmatism and piety, there can be no doubting her courage, determination, and singular successes in improving the lives of working class women and girls. So, when I was in her native Northumberland, I sought her grave in Saint Gregory’s churchyard in Kirknewton to pay her the huge respects she undoubtedly merits.

For more on Josephine Butler see Sarah C. Williams When Courage Calls: Josephine Butler and the Radical Pursuit of Justice for Women (2024)