In the mid-1980s I lived in a flat in a Georgian conversion in Bath. In the flat above me lived a student of English literature. As I passed him in the hall one afternoon he glanced into the contents of my basket and exclaimed “Aha! You know.” I followed his gaze, but my greengrocery did not disclose any clues. In response to my blank look, he delved amongst the potatoes and carrots to extract a fat volume which he flourished. “You know about her,” he insisted stabbing his finger at my copy of Fanny Burney’s The Wanderer. The truth was that I was finding this massive tome tedious, and my knowledge of Fanny Burney was insufficient to allow me to engage with confidence in any discussion of her work with a specialist in English Literature. As I hesitated Robert enlightened me, “ She lived in your flat. You didn’t know?” I was surprised; there was no blue plaque on 23 Great Stanhope Street although there was one on 14 South Parade where Fanny had lodged with her friend Mrs. Thrale for three months in 1780.

Robert however was right: Fanny Burney lived for three years, from 1815 to 1818, in Great Stanhope Street with her husband General d’Arblay and their son Alexandre. D’Arblay, a French émigré, supporter of the constitutional monarchy, had fled France in 1792 forfeiting his property. Fanny had already found fame with her first two novels Evelina and Cecilia which had earned the praise of Dr. Johnson and the admiration of Jane Austen. They met through Fanny’s sister when the emigres were living near her at Juniper Hall, and spent their first ten years together in Surrey, supported by the proceeds of Fanny’s latest novel Camilla . In 1802 when an amnesty removed d’Arblay from the proscribed list of émigrés and permitted his return to France they hastened there hoping to regain his property and his army pension, but with the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars they became trapped. During their enforced residency Fanny completed The Wanderer. After the restoration of 1814 d’Arblay held a position in the King’s Guard and during the Hundred Days that followed Napoleon’s escape from Elba he joined Louis XVIII but, wounded by a kick from a horse, he missed seeing action at Waterloo. The wound turned gangrenous, and septicaemia developed. Discharged from the army d’Arblay returned to England with Fanny who hoped that the Bath waters would aid his recovery. As she wrote in her journal, they sought “cheap lodgings” in Bath, for The Wanderer had not sold well, the readers who had embraced her earlier novels sharing my lack of enthusiasm for this one, and so they came to 23 Great Stanhope Street in “an unfashionable quarter of Bath.” Fanny’s diaries reveal that their drawing room and her bedroom were on the first floor. On the second floor slept the general (in what was now my bedroom) and their son (in my sitting room.) A walk-in closet was a book room (my kitchen). Their landlady, Mrs. Brenan, occupied the ground floor and basement, cooking for them, cleaning, making fires, and emptying chamber pots. There was no sign of the fireplaces in my day: the rooms had been gutted. Happily there was no sign of the chamber pots either, for the general’s bedroom had been partitioned to provide a bathroom.

The family remained in Great Stanhope Street until the general died, the Bath waters having failed to alleviate his suppurating wound, jaundice, and limp.

I often fell asleep conjuring up his sickly presence in what had once been his room, and that of his prolific and devoted wife busy writing below.

In search of their graves, I visited Saint Swithin’s parish church. The church had been rebuilt on the site of an older foundation in 1775 to house its growing congregation in fashionable Bath. By 1800 it was the second largest parish in England after St. Pancras, London.

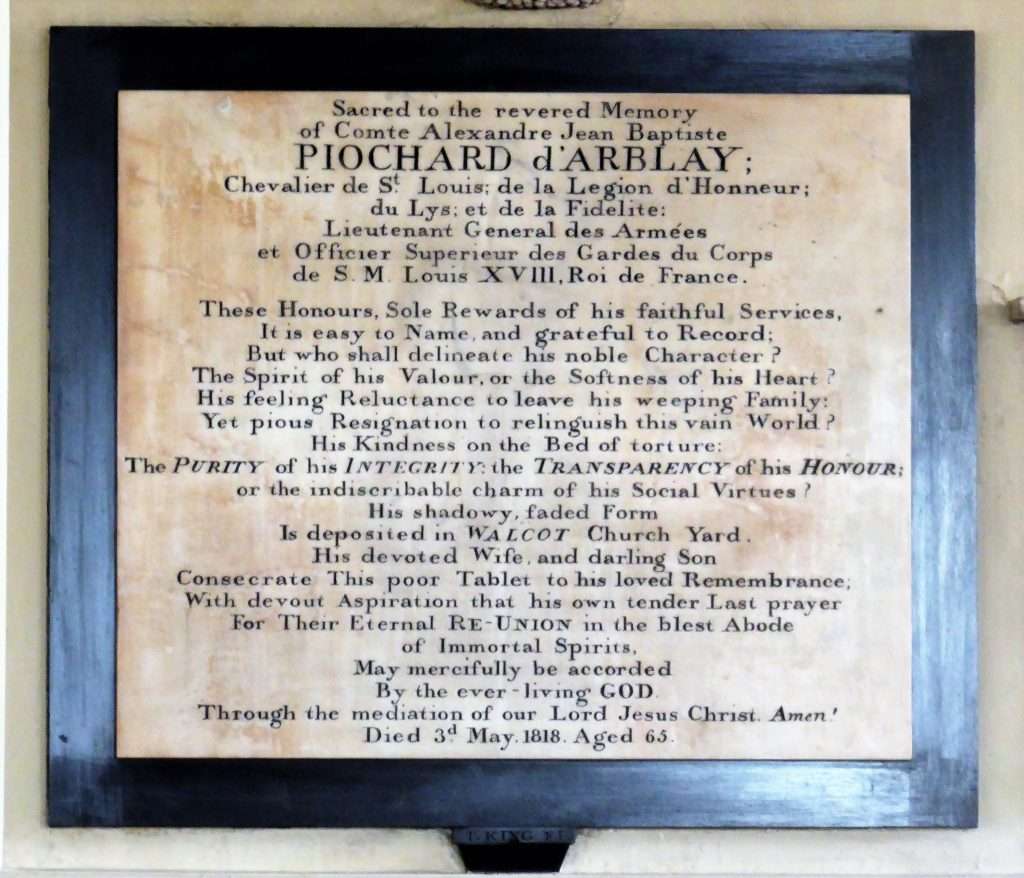

St. Swithin’s cemetery, the Lower Burial Ground, lay across Walcot Street and down the hill from the church. Fanny buried the general there in May 1818 with a black marble headstone, which subsequently disappeared, and she had a memorial tablet expatiating on his virtues erected in the church.

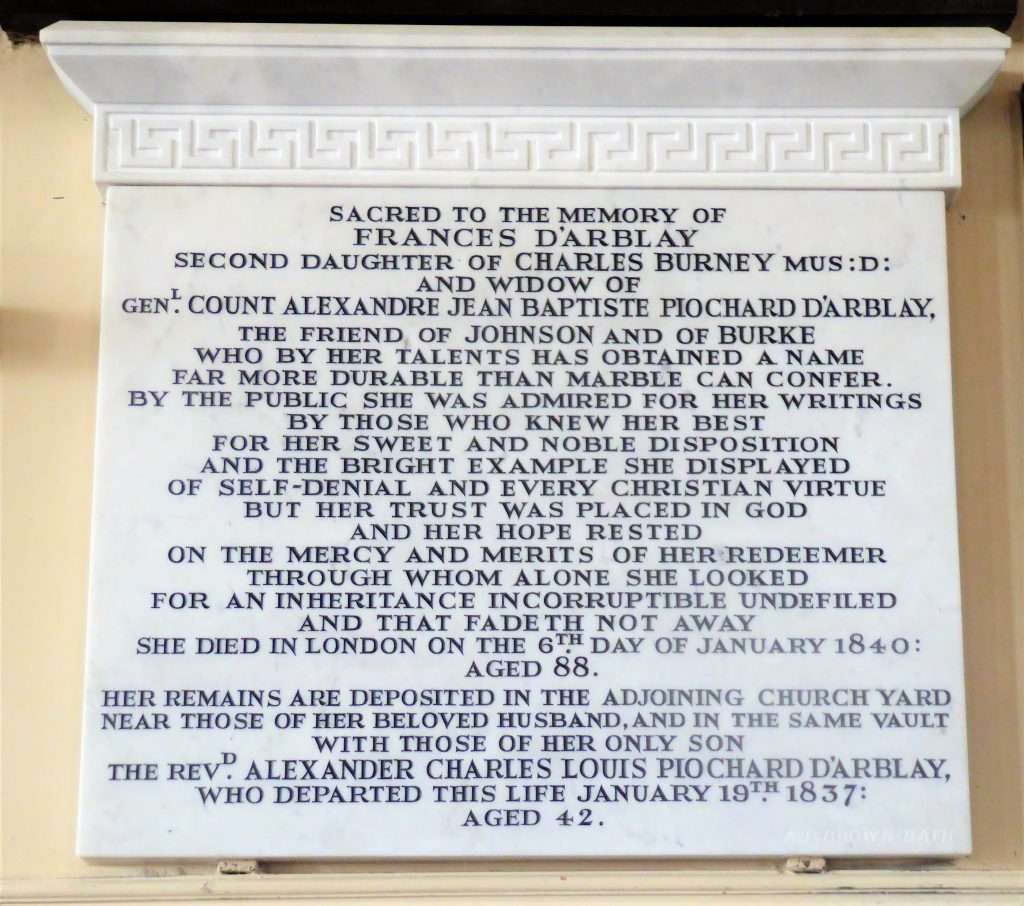

In 1837 their son was buried near his father, and in 1840 Fanny was placed in the same grave and another memorial tablet raised in the church. By 1906 however their gravestone was weathered and neglected, and Burney descendants replaced it with a new tabletop monument. In 1955 when part of the burial ground was cleared for proposed redevelopment, the PCC moved Burney’s three-ton stone up the hill and over the road to a small enclosure beside the church, where it remains today, a lonely cenotaph separated by railings from the bustle of Walcot Street on one side and The Paragon on the other.

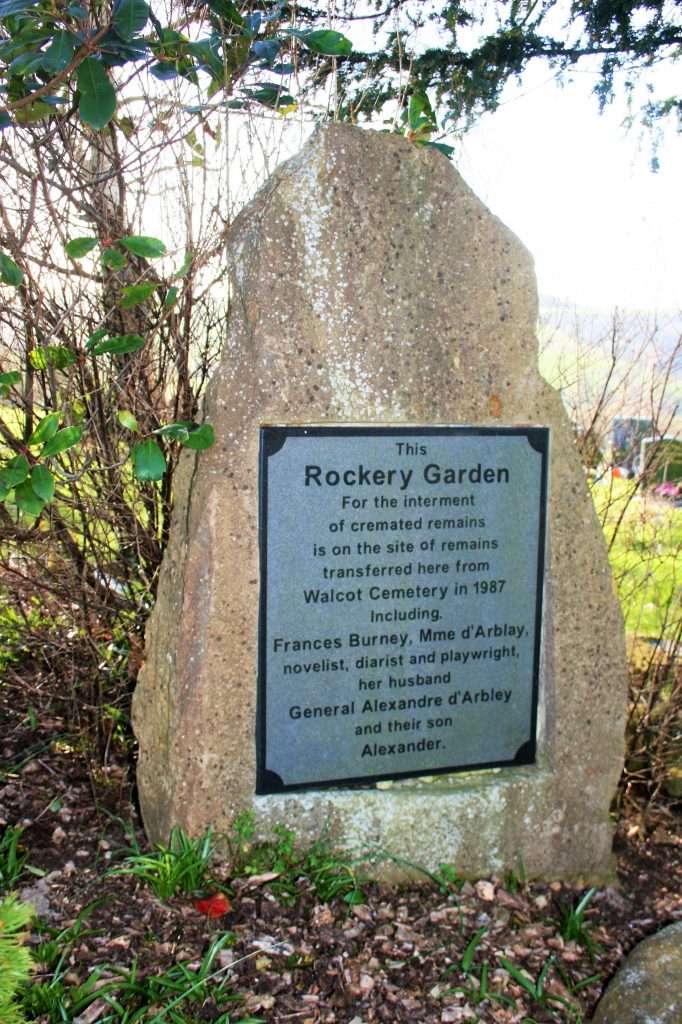

In 1987 remains from the cemetery, including those of Burney, her husband and son, were exhumed and reinterred beside The Rockery Garden in the municipal cemetery at Haycombe on the south side of Bath.

The Lower Burial Ground, its few remaining graves clustering round the mortuary chapel, remains undeveloped.

Fanny’s memorial plaque in the church was destroyed when a new organ was installed against the wall in the twentieth century but in 2013 the Burney Society funded a new memorial reproducing the exact wording of the original from photographs.

Along with the general’s memorial it is housed amongst a truly magnificent collection in the church for the general was not the only one for whom the Bath waters proved less than efficacious.

But Fanny’s spirit is not wandering the church and its precincts nor is she down in The Lower Burial Ground nor up in Haycombe Cemetery: she is busy updating her journal, perhaps even plotting another novel, shorter this time, in her rooms at 23 Great Stanhope Street. I know, I lived with her.