A particularly pretentious estate agent, more than usually given to hyperbole, is currently offering for sale the “former home of Charles and Mary Lamb.” The sixteenth century Clarendon Cottage located on the quaintly named Gentleman’s Row in Enfield was never the Lambs’ home, but they spent their summer holidays in the then rural location between 1825-27. The house they actually bought in Enfield in 1827 was The Poplars at Chase Side.

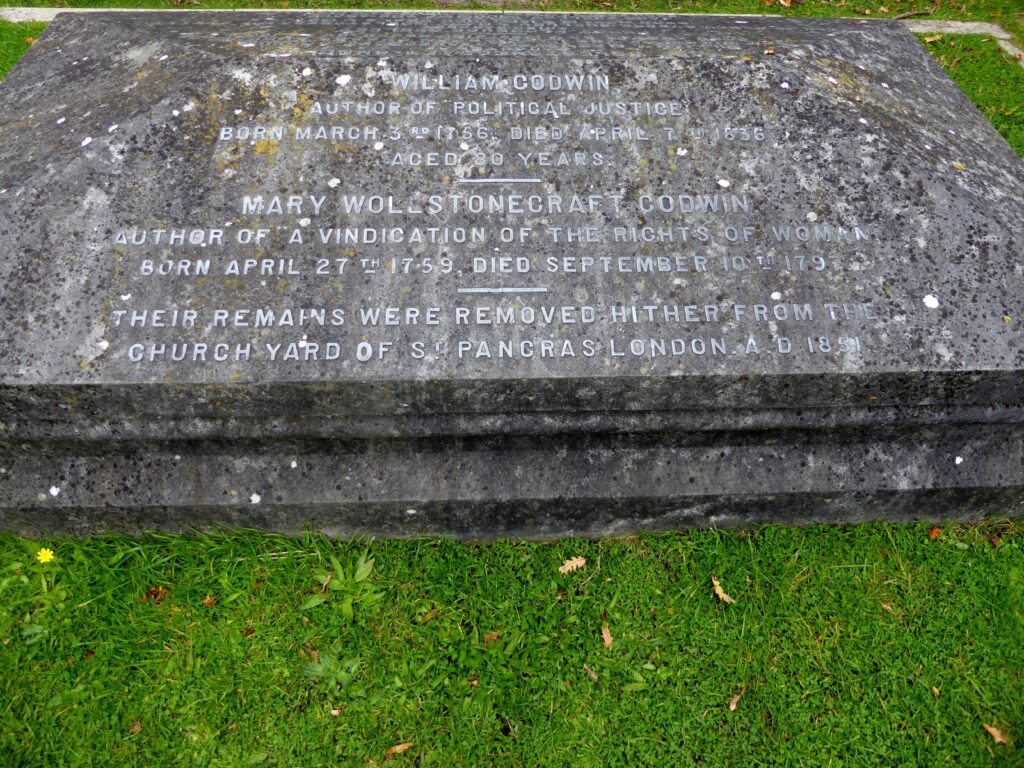

The siblings were born and spent their early lives in the Inner Temple where their father was employed as a lawyer’s clerk. Charles (1775-1834) became a clerk to the East India Company, a job he held for twenty five years, alongside publishing poetry and prose. His sentimental poetry, even The Old Familiar Faces, the most celebrated of the poems, is little read today, but the Essays of Elia still have their admirers. Familiar to a far wider audience however are Lamb’s Tales from Shakespeare. Designed to introduce children to Shakespeare’s plays they are clear, readable prose summaries, which nonetheless retain much of the Shakespearian language, while leaving out subplots, violence, and sexual references. The approach is reverential, reflecting Lamb’s strange belief that the plays should be read rather than staged to avoid misinterpretations. Charles tackled the tragedies and Mary the comedies, although they were all originally published under Charles’ name. The history plays they avoided. The Tales were published and sold by William Godwin and his second wife who specialised in juvenile literature, also publishing a children’s version of the Odyssey and volumes of poetry for children. And, despite their limitations, the Tales were an immediate best seller and have never been out of print.

Moreover, the Lambs held a weekly salon attended by literary figures including Southey and Coleridge with whom Charles had been at school. Through Coleridge they became friends with Wordsworth although the latter clashed with Charles who did not share his romantic fascination with nature and the countryside. In a letter to Wordsworth Charles wrote,

Separate from the pleasure of your company, I don’t much care if I never see a mountain in my life. I have passed all my days in London, until I have formed as many and intense local attachments, as any of you Mountaineers have done with dead nature. The Lighted shops of the Strand and Fleet Street, the tradesmen, and customers, coaches, wagons, playhouses, all the bustle and wickedness about Covent Garden, the very Women of the town, the watchmen, drunken scenes, rattles, coffee houses, steams of soups from kitchens, the pantomimes, London itself, a pantomime, a masquerade. The wonder of these sights impels me into night-walks about her crowded streets, and I often shed tears in the motley Strand from fullness of joy at so much Life.

How then did Charles Lamb come to buy a property in the former market town of Enfield in Middlesex, reduced to little more than a village surrounded by green meadows in the years that he lived there, far from the sounds, shops, and entertainments of London? A family tragedy lies behind this, the penultimate of many moves which the siblings made.

Both Charles and Mary had periods of mental illness throughout their lives, Mary’s the more severe and more likely to lead to aggression. Charles had spent six weeks in an asylum in 1795. Mary meanwhile was caring for their senile father and incapacitated mother, while supplementing their income with dress making. One day she lost her temper with her young apprentice, treating her roughly. When her mother reproached her, Mary responded by stabbing and fatally wounding her with a kitchen knife. Following their mother’s death Charles took responsibility for his sister, refusing to have her committed to a public mental institution. She was released into his care, and they remained together for the rest of their lives, she caring for him during his bouts of drinking, he for her during her recurring illness. The burden must have been considerable: when they travelled, they took a straitjacket, and Mary was periodically confined to an asylum. Yet it was during the early years of the nineteenth century that their writings became successful, their financial position improved, they expanded their literary and social circle, and established their salon.

But with Charles’ drinking and Mary’s madness they were not popular tenants, often subject to malicious gossip, and easily evicted from their accommodation. They moved from Holborn, back to the Inner Temple, to Covent Garden, and to Islington, before Charles decided that although he would miss London, rural Enfield with its fresh air and quiet would be better for Mary’s health.

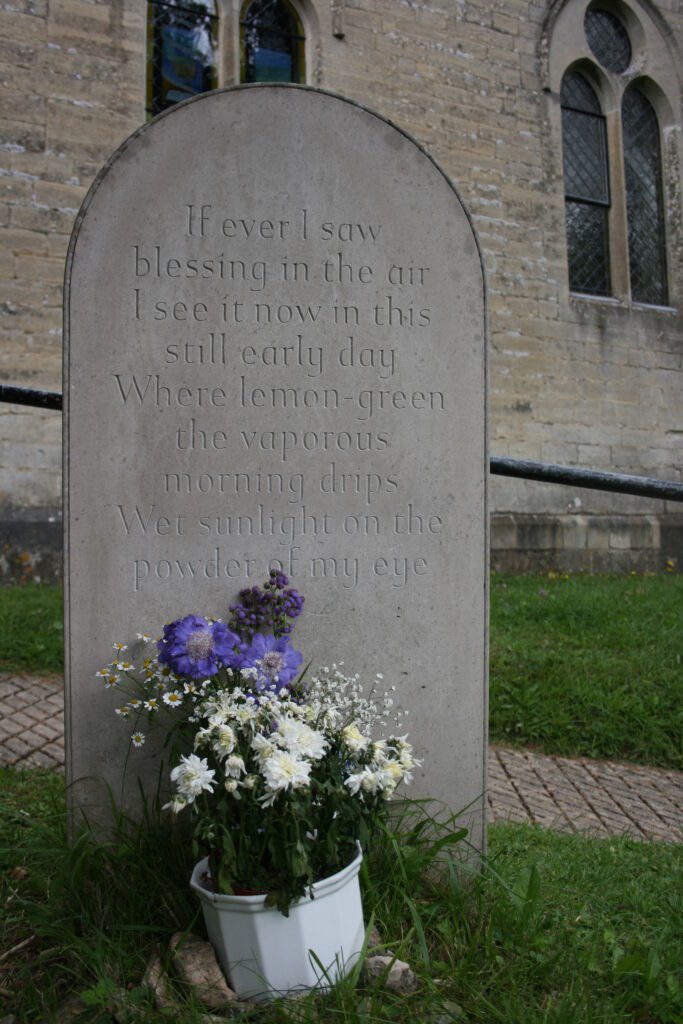

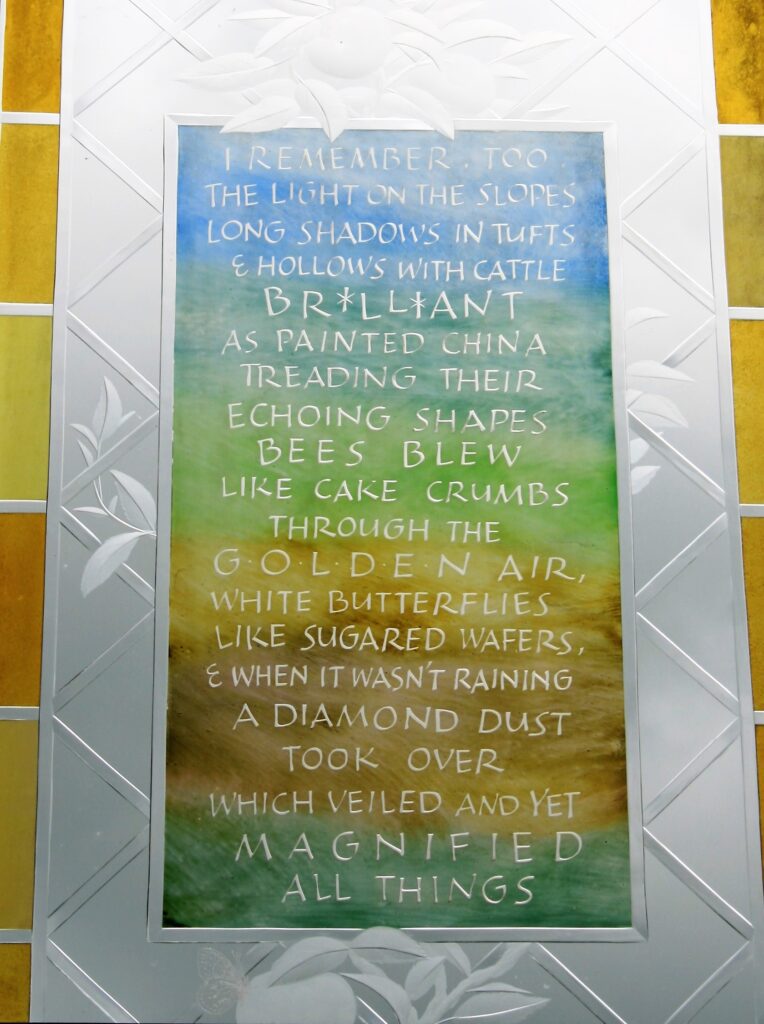

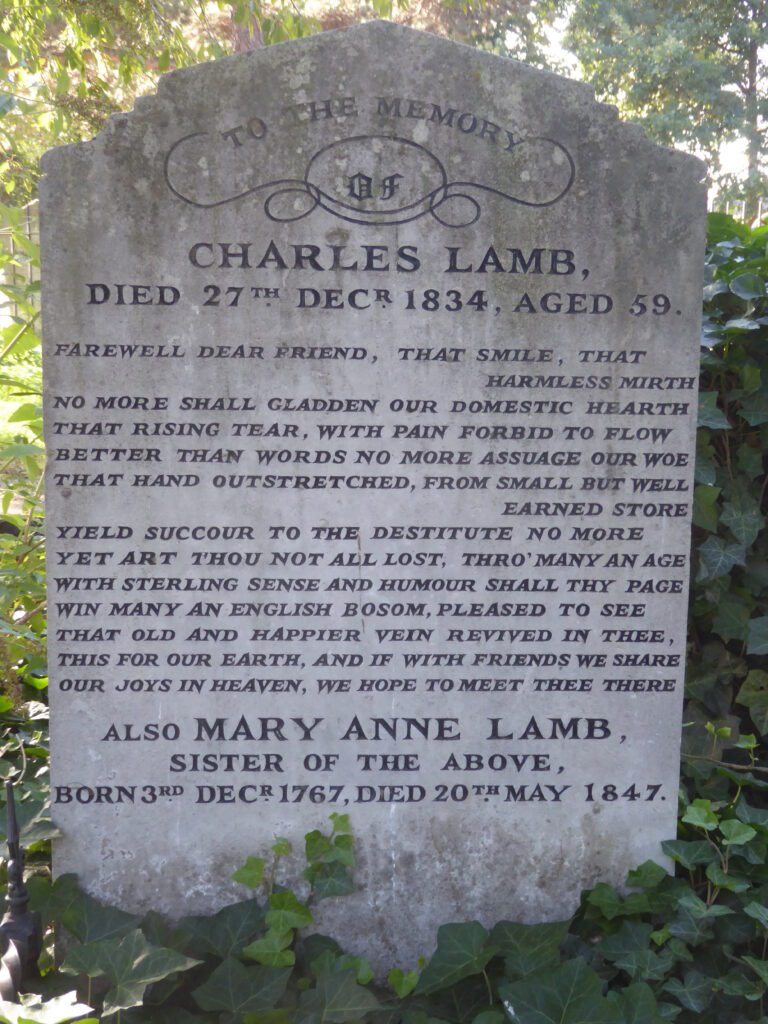

Their final move from Enfield in 1833 was to Bay Cottage, Church Street, a private asylum in the nearby village of Edmonton where Mary was the sole patient. Her brother moved into the cottage with her, but following a fall a year later, he developed a streptococcal infection in a cut and died. He was buried in All Saints churchyard, Edmonton where his stone bears an epitaph composed by Wordsworth at Mary’s request. Mary lived on until 1847 when she was buried beside her brother.

The cottage in Edmonton, today bearing a blue plaque and renamed Lambs’ Cottage, still stands, as does the fifteenth century church. And lingering in the precincts of the verdant churchyard I found it easy to imagine that the stout tower and the graves drowsing under a mantle of ivy still lay at the heart of the village which Charles and Mary knew.

But it is long since the sprawl that is Greater London engulfed both Enfield and Edmonton. After the railways and the trams reached the former villages in the 1840s industrialisation followed and they became part of the conurbation of north London. New housing in the interwar period led to their merging with other towns to form the London Borough of Enfield. So, in the end Charles Lamb was surrounded by his beloved London albeit an outer suburb, not the glamourous, raucous heart of it that he loved so much.

By the 1970s the industry and manufacturing had gone again, and today estate agents try, with dubious veracity, to reinvent the small conservation areas in the tired, rundown suburbs as the villages they once were, enlisting the help of famous names to make their properties seem more desireable.