The bus headed north from the centre of the city, and as it reached Walton the lack of investment in this deprived and battered suburb of Liverpool was apparent. Through the dirty windows I watched the shuttered shops and red brick terraces passing by. Walton is mentioned in the Doomsday Book as a town in its own right but by the late nineteenth century it had been swallowed up by the advance of Liverpool. Not quite sure where I was going I got off at the Clock Tower. It is an impressive, if daunting and forbidding structure, built in 1868 as the centre piece of the Union Workhouse. In the twentieth century the workhouse became Walton Hospital. Since the latter was demolished the clock tower building alone remains looming over a new housing estate.

But this was not what I had come to see. I knew that somewhere nearby was the Liverpool Parochial Cemetery, opened in 1851 as the growing population overwhelmed the central churchyards, and that there Robert Tressell was buried.

As I turned down Rawcliffe Road an unexpected delight awaited me, for the cemetery is no longer in use and has been taken over by the Rice Lane City Farm. The graves have been tidied up and the farm, established by the local community 40 years ago, is open to all every day of the year. Small children ran around delighted by the ducks, pigs, sheep, goats, and Ness, the donkey. Scattered groups sat in the weak spring sunshine eating picnic lunches, and Walton suddenly seemed a happier, more cheerful place.

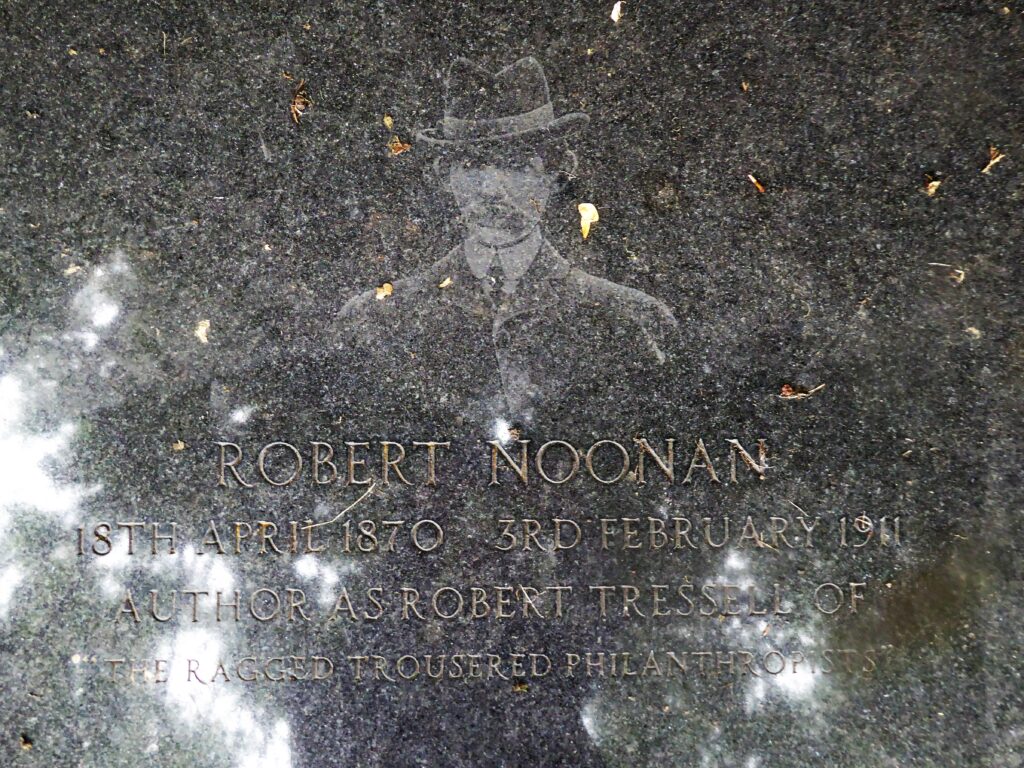

But what of Robert Tressell? The man I was seeking was born in Dublin but emigrated to South Africa where he was employed as a housepainter and sign writer. Following a failed marriage, he returned to England with his daughter Kathleen, and they settled in Hastings where he pursued his trade. He was a founder member of the Hastings branch of the Marxist Social Democratic Federation but is most remembered for writing what has been described as the first working class novel in England: The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists. It was as author of this book that Robert Noonan assumed the pen name Tressell, a word play on the trestle table with which painters work.

Set in 1906, the partly autobiographical novel is a clarion cry for Socialism. It describes a group of painters and decorators employed to restore a house in a world of stagnant wages and soaring profits. The poverty and near starvation in which the workers live, without proper food and clothing for themselves or their children, in cold cheerless homes, a prey to sickness, the workhouse, and early death, contrasts with the wealth and ease which their employers enjoy. Such is the precarious nature of the workers’ existence that a man murders his children rather than see them starve, an incident which Tressell based on a real case.

Owen, the main character, refers ironically to his fellow workers as philanthropists because they hand over the results of their labour to their employer without question, accepting that there is a natural order of rich and poor, of rulers and ruled. They are working class Conservatives, voting in ignorance, relinquishing self-respect and dignity, accepting that they should have only the necessities of existence, that “leisure, books, theatres, pictures, music, holidays, travel, good and beautiful homes, good clothes, good and pleasant food” are not “for the likes of them.”

Owen tries to explain Socialism to his fellow workers, to make them understand that the pathetic measures, such as smoking in the bosses’ time and minor pilfering, by which they attempt to “get some of their own back,” will change nothing. Revolutionary change, the proper valuing of labour power and the elimination of hereditary wealth is needed, he argues, to alleviate inequalities for good. But even Philpot, a good man who would happily pay another halfpenny on his rates to provide food for hungry school children, cannot countenance the possibility of changing the system.

Sometimes the novel becomes didactic as Owen lectures his fellow workmen on Marxist theory. At other times it is sentimental. But the chapters which portray the men’s home lives, their troubled relationships, their children’s games, their friendships, their weaknesses, the accidents at work, the lure of the public house, and the annual beano, are vivid and real. And with echoes of William Morris, he portrays the frustrated craftsmanship with which the workers seek to express their personalities in lieu of the “scamping,” the cheap, rushed jobs required by their employers to maximise profits.

Tressell hoped that by publishing the novel he might convert his fellow workers and, knowing that he had tuberculosis, provide money for his daughter if he died. But the handwritten manuscript was rejected unread. In 1910 he decided to emigrate to Canada in search of a better life, aiming to send for Kathleen once he was established. Aged forty, he fell ill and died of TB in Liverpool Infirmary while waiting for a ship. Kathleen had neither the money to pay for her father’s funeral nor the means to attend it. Tressell was buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave.

In 1914 Kathleen sold the novel to a publisher; since then it it has never been out of print, and it is frequently credited with helping to win the 1945 election for Labour.

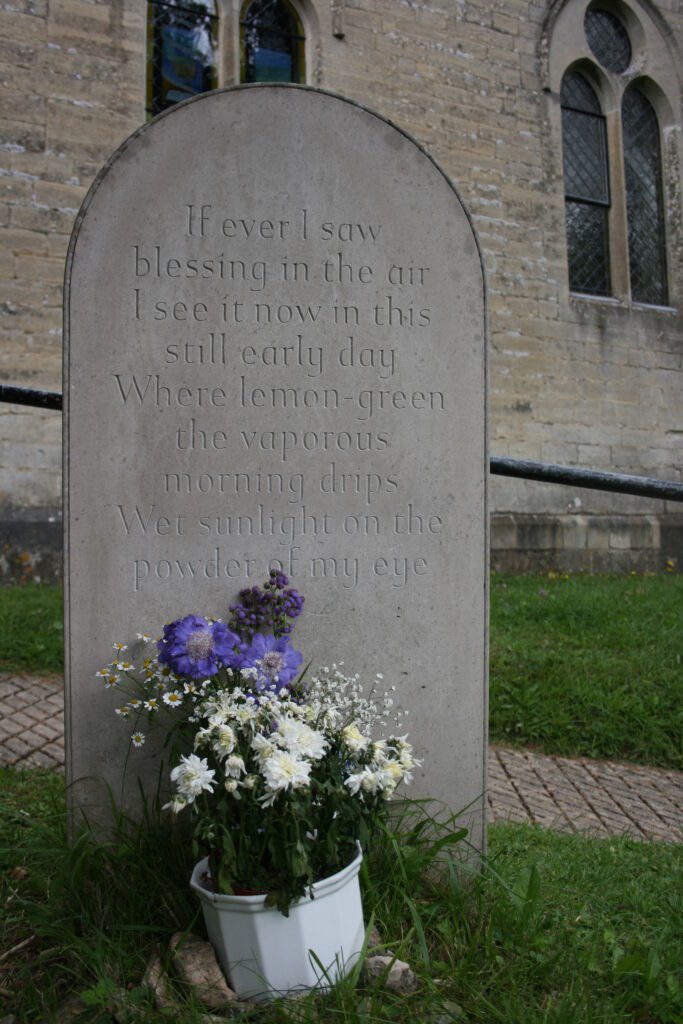

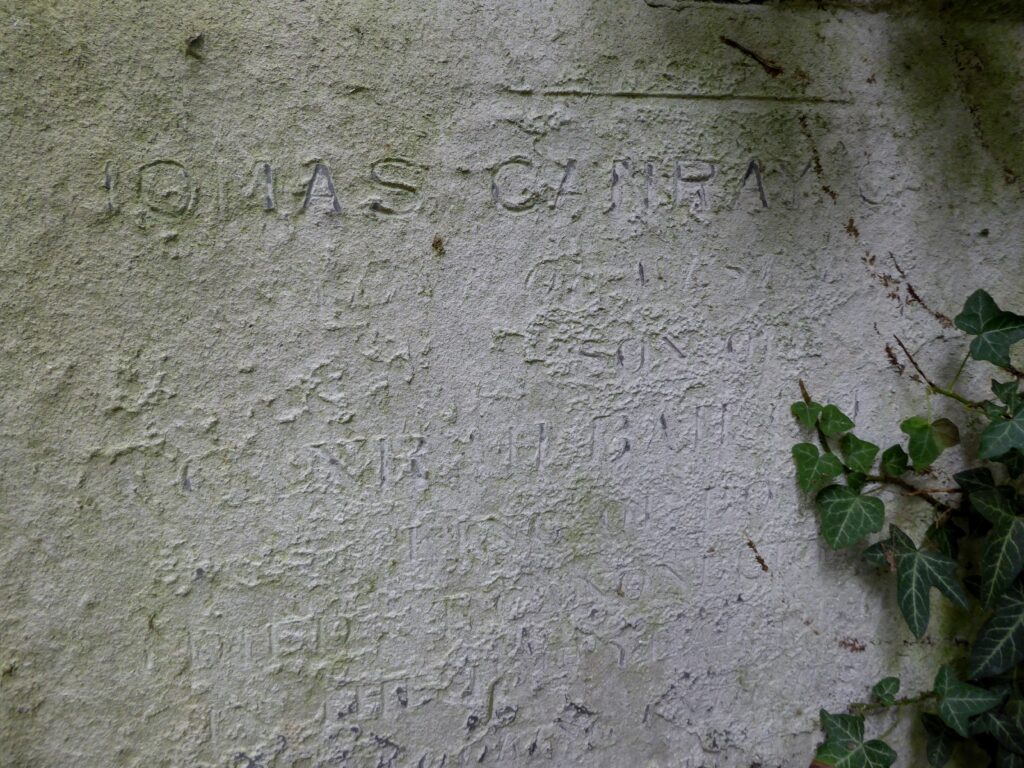

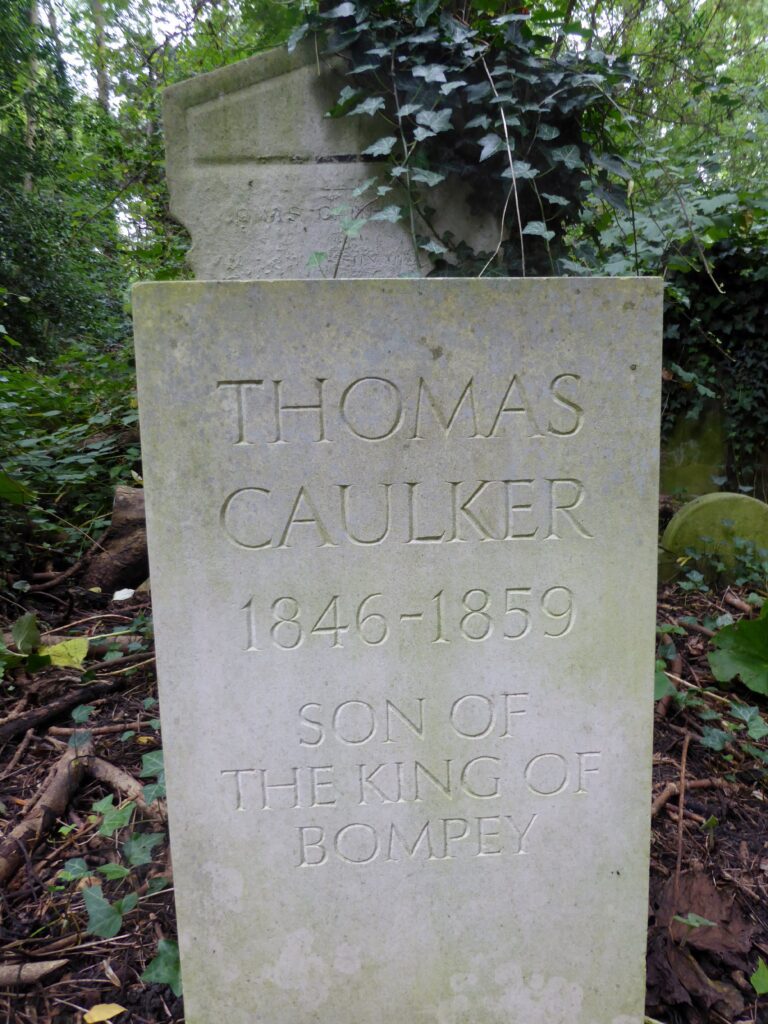

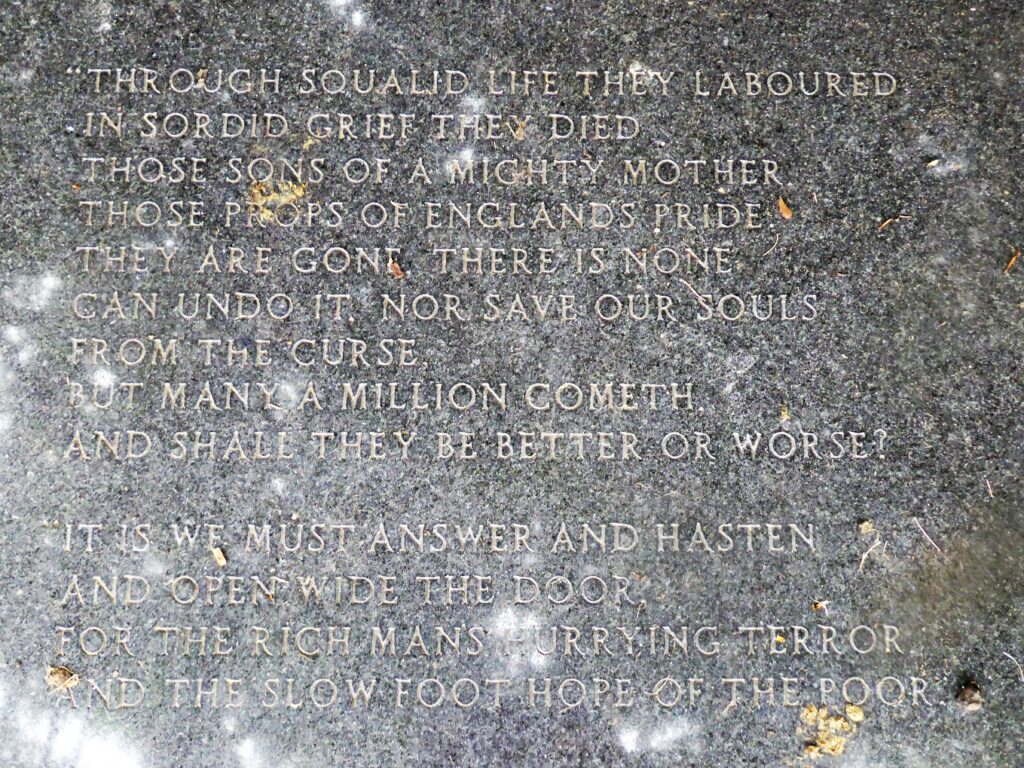

In 1970 the historian Alan O’Toole used cemetery records to locate the grave where Tressell lay with twelve other paupers buried on the same day. Local Socialists and Trade Unionists unveiled a stone in 1977. Made of Swedish granite donated by Swedish Trade Unions, it bears a portrait of Tressell, the names of the twelve others buried with him, and an extract from William Morris’ poem The Day is Coming.

Through squalid life they laboured, in sordid grief they died,

Those sons of a mighty mother, those props of England’s pride.

They are gone; there is none can undo it, nor save our souls from the curse;

But many a million cometh, and shall they be better or worse?

It is we who must answer and hasten, and open wide the door

For the rich man’s hurrying terror, and the slow-foot hope of the poor.