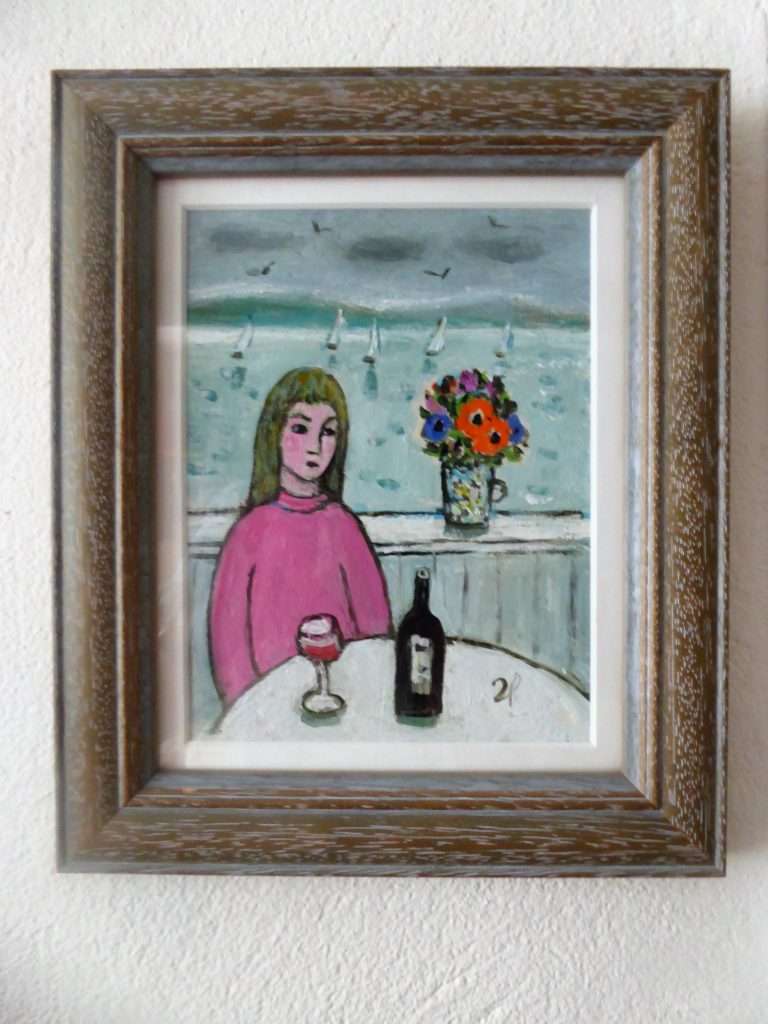

It was a Sunday afternoon of penetrating, unrelenting, rain interspersed with claps of thunder when, shivering as the chilly water trickled under my coat collar and down my neck, I took refuge in the Wren Gallery in Burford. Here was warmth, light, and, magically appearing in front of me, a platter of smoked salmon sandwiches. Surprised but delighted I took a sandwich whereupon a tray appeared bearing glasses of white wine. “Please” said Gill Mitchell “eat as many as you can and have another glass of wine. Our exhibition is opening today but, in this weather, there won’t be anyone to eat all these sandwiches.” Happy to oblige I munched and sipped my way around the gallery and there discovered the wonderful world of Joan Gillchrest. She was a member of the talented Gilbert Scott family of architects, and after studying art in Paris and London, driving an ambulance during the war, and an exotic post war life as a model, she settled in the Cornish town of Mousehole in the 1950s. Her captivating paintings reminded me of the works of Alfred Wallis and LS Lowry: small, bent people struggled against the winds outside grey Cornish chapels, mines, and engine houses; they walked dogs on beaches and attended weddings and funerals under louring Cornish skies. Other paintings were suffused with the sunlight of a golden summer’s day: there were lighthouses, seabirds, ships in Mousehole harbour, ladies drinking sherry in the Lobster Pot Hotel. Views of the sea seen through the glorious tangle of plants in Joan’s greenhouse also featured her succession of rescue cats who formed the Titus dynasty peering through the foliage.

I returned to the gallery the following week to buy two small paintings, promising myself that in the future I would buy a larger canvas, but as my finances improved so did the value of Gillchrest’s work. So instead, I have shamelessly treated the Wren as though it were a public gallery where I have viewed ever-changing exhibitions of Joan’s work, and when, after Joan’s death, Gill Mitchell published Joan Gillchrest: a Life in Pictures I enjoyed a wider range of the paintings.

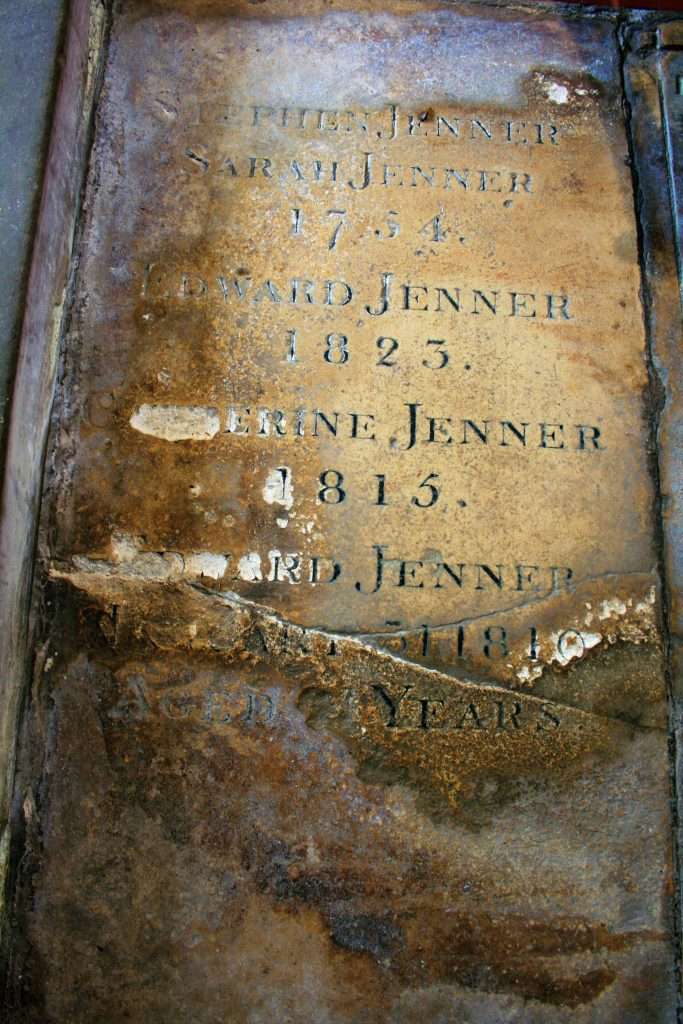

In Paul churchyard above Mousehole a rough-hewn granite stone marks Joan Gillchrest’s grave and sleeping at the base of it last time I visited lay a small, stone, black and white Titus concealed behind exotic blooms which I moved to one side for the photograph before tucking him back beneath them.

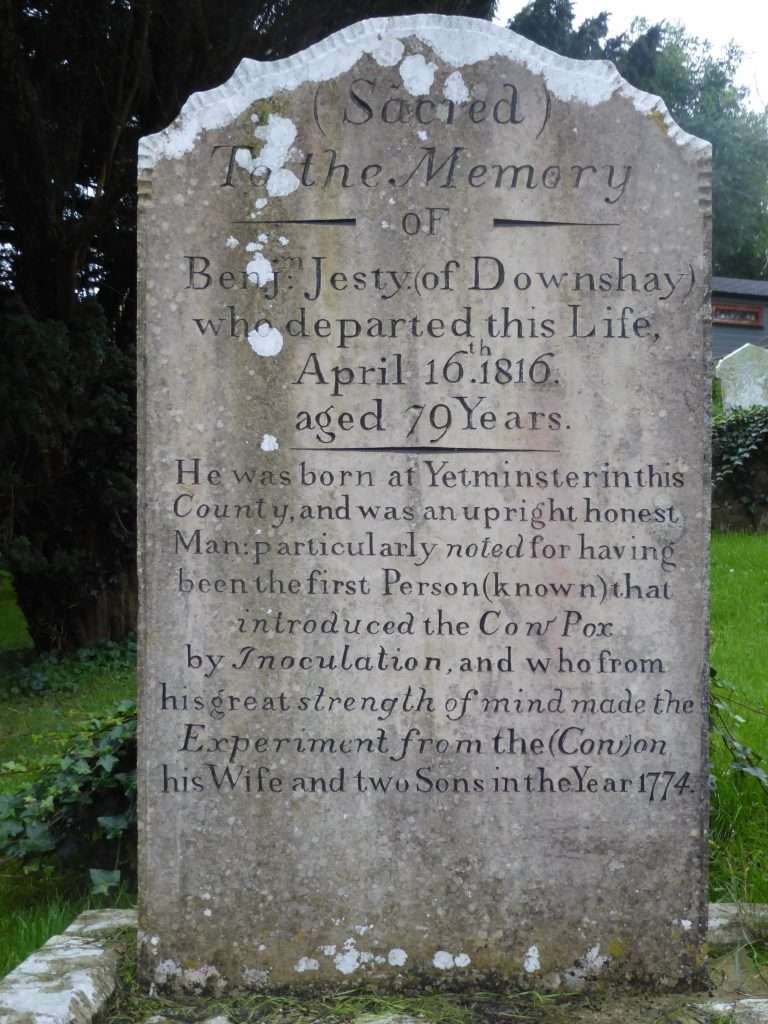

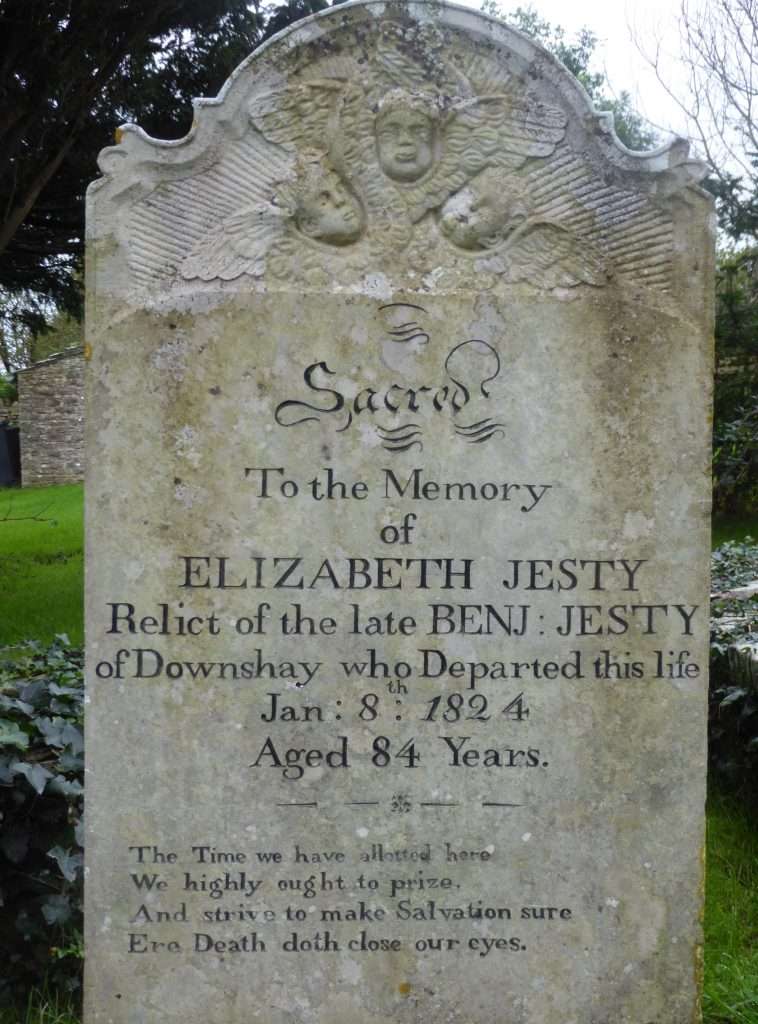

In her book Gill Mitchell comments that although Joan never knew Alfred Wallis she was open about his influence on her work and would visit his grave in St. Ives to “say hello to Alfred,” indeed her painting “Saying Hello to Alfred” features the grave at Barnoon cemetery overlooking Porthmeor beach and Tate St. Ives, home to some of his paintings. The Cornish fisherman sold little in his lifetime. He began painting as he said “for company” after his wife died, painting his ships, harbours, and lighthouses on old pieces of cardboard and grocery boxes. Even after Ben Nicholson, Christopher Wood and Jim Ede discovered and promoted his work he lived in poverty and died in Madron workhouse. The artistic community of St. Ives paid for his grave which is one of the loveliest I know, the tiles designed by Bernard Leach portraying a lighthouse, which Wallis might have painted himself using the same subdued colours, with a small figure clambering up the steps.

I have found no reference to any influence of Lowry on Joan Gillchrest but since her hunched figures battling the elements reminded me of his, come north with me, far from the lighthouses, rocks, bays and boats of Cornwall . At the Manchester School of Art LS Lowry studied under Adolphe Valette whose own large impressionist canvases of industrial Manchester seen through a smog- filled haze occupy a magical room in Manchester Art Gallery. Lowry famously worked as a rent collector while caring for his widowed and bed ridden mother in Pendlebury, painting at night after she was asleep. Today the largest collection of his work is displayed at the Lowry Gallery in Salford Quays but to “say hello to Lowry,” I took the bus to Manchester’s Southern Cemetery in Chorlton-come-Hardy. At the largest municipal cemetery in the UK, I anticipated a daunting quest, but in the lodge the custodian supplied me with a plan and focused my search by pointing to a photograph on the wall of his own daughter standing beside Lowry’s grave. In the serried rows, a conventional white cross marks the grave of Lowry’s parents with his own name added inconspicuously on the side of the base. But I might have spotted it without help, for in front of it, in lieu of the usual vase of flowers, was a pot full of paint brushes.