At last, the sun is out, the days are warmer and longer, and the holiday season beckons. Nothing raises my spirits so much as a packed suitcase, and the prospect of a journey. Ideally an eager lover should meet me at an exotic train station or airport, but a local guide with my name spelled out on a handheld sign will do. Indeed, I will happily descend into the bowels of an unknown metro or abandon myself to the hustling taxi drivers who swarm like locusts awaiting disorientated travellers. The destination and the transport do not even have to be glamorous: bags in the back of the car, the bossy lady from Google Maps issuing terse directions as I miss the correct exit from the roundabout for the third time, I will advance on the most unprepossessing of English towns, firm in my conviction that there are at least Ten Interesting Things to See in any previously unexplored location. Hearing me say this, a friend once challenged me with her hometown of Middlesbrough; honestly, it could not have been easier.

No surprise then that one of my heroes is Thomas Cook (1808-1892), the man who established the world’s first package tour. Born in Derbyshire, he moved to Leicester in his twenties and established a business as a bookseller and printer. He joined the Temperance Movement and organised his first excursion in 1841, hiring a train and carriages from the newly established Midlands Counties Railway to transport temperance campaigners from Leicester to a rally in Loughborough. Four hundred and eighty-five people made the round trip of twenty-two miles in third class open tub cars. They paid one shilling each which also covered the cost of a meal and the services of the band which accompanied them. Over the next four summers Thomas Cook coordinated similar expeditions to Nottingham, Derby, Birmingham, and Liverpool for members of Temperance Societies and Sunday Schools.

In 1846, expanding to include trips for the general public, he inaugurated his first tour of Scotland, a little blighted by the absence of restaurant and lavatory facilities on the train. Then followed tours of Wales and Ireland. Joseph Paxton, the architect of the Crystal Palace, encouraged him to arrange day trips from Yorkshire and the Midlands to the Great Exhibition in London, and in the course of 1851 he transported 150,000 people to the event in Hyde Park.

Cook opened his Temperance Hall and Hotel in Leicester in 1853. The hotel incorporated his tourism office and his family accommodation. The Temperance Hall offered entertainment to rival the ubiquitous public houses, with concerts, lectures, magic lantern shows and readings, the latter on occasion performed by Charles Dickens.

In 1855 came the first excursion abroad with a “grand circular tour” through Belgium, Germany, and France. Cook negotiated reduced rates and customised schedules with railway companies in return for block bookings. He provided a package of travel, accommodation, and food, personally planning the routes and escorting the trips.

By 1868 Cook had introduced “hotel coupons” which independent travellers could exchange for meals and accommodation at any hotel on “Cook’s List”. In 1874 came “circular notes”, a popular form of traveller’s cheque, the first ones specifically exchangeable for Italian lira at a predetermined rate.

Having brought mass tourism to Italy, for which present day Venice may not thank him, he moved on to America where his “circular tickets” facilitated travel on 4,000 miles of railways.

Cook’s travel office began to sell guidebooks, luggage, telescopes, and suitable footwear for more ambitious expeditions. By 1869 he had hired two steamers to transport his tourists up the Nile. So popular were these tours that the Nile was dubbed “Cook’s Canal.”

His experimental Round the World Tour of 1872 was so successful that it became an annual event. Cook had taken the Grand Tour out of the hands of the very wealthy, opening the world to an ever-widening demographic.

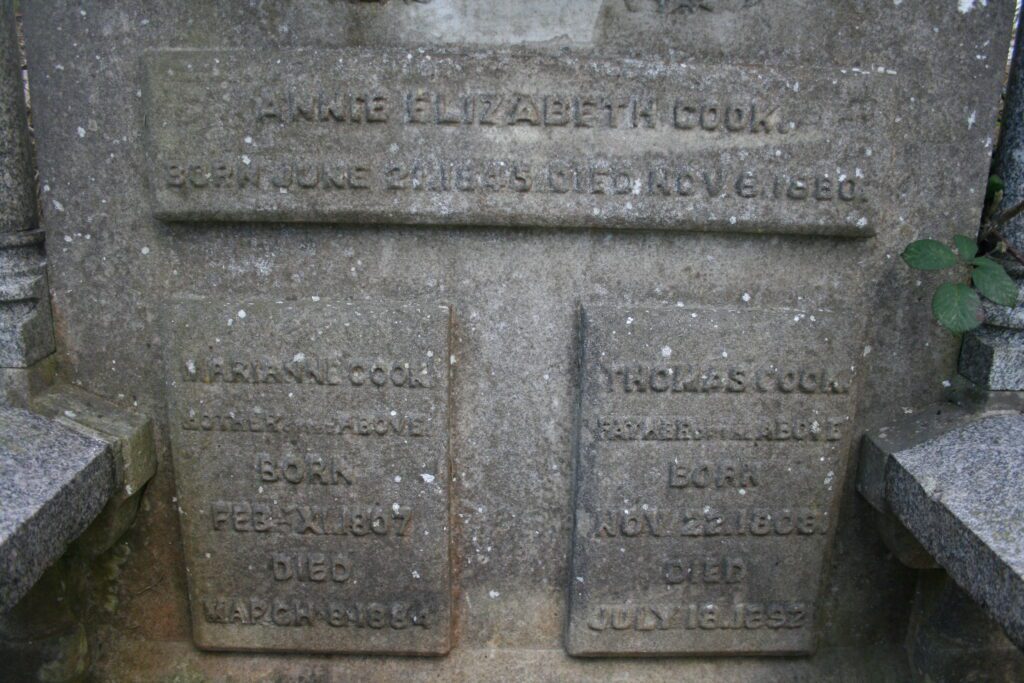

The Cook family grave lies in Welford Road cemetery, Leicester.

It incorporates individual tablets remembering: Cook’s daughter, Annie Elizabeth Cook, who unfortunately died in a bath in 1880 having inhaled poisonous fumes from a water boiler; his wife Marianne Cook, died 1884; and Cook himself who died in 1892.

Above the tablets it bears a conventional epitaph from Isaiah 40, 6-8,

“All Flesh is Grass,

The Grass Withereth

The Flower Fadeth

But the Word of our God shall stand Forever.”

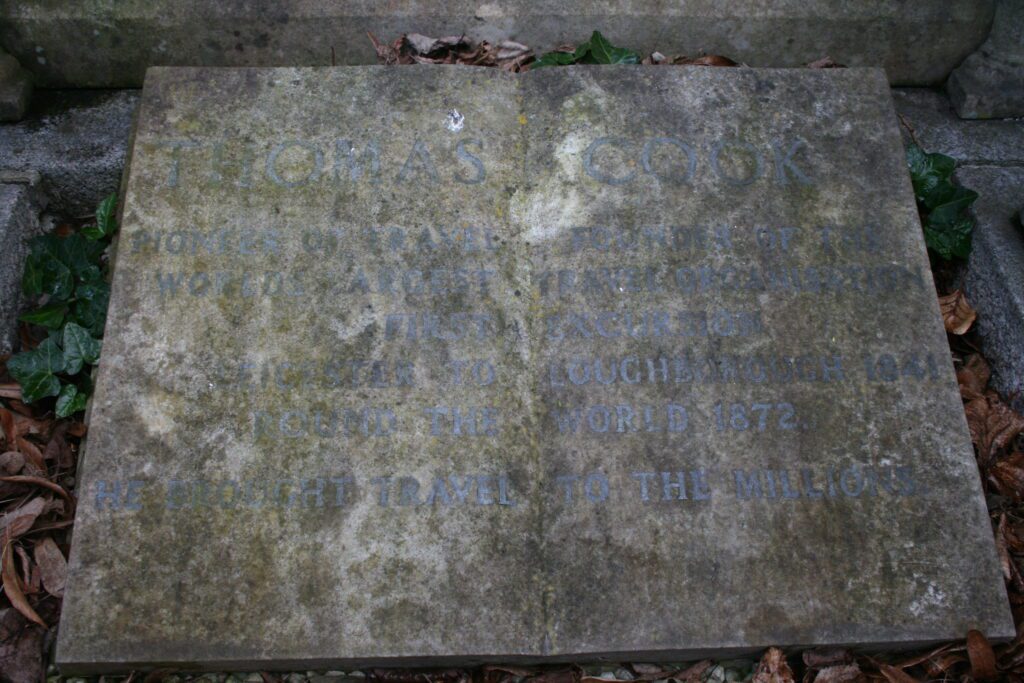

But far more arresting is the lichen covered open book at the foot of the upright stone:

Thomas Cook

Pioneer of Travel, Founder of the

World’s Largest Travel Organisation.

First Excursion

Leicester to Loughborough 1841

Round the World 1872

He Brought Travel to the Millions.

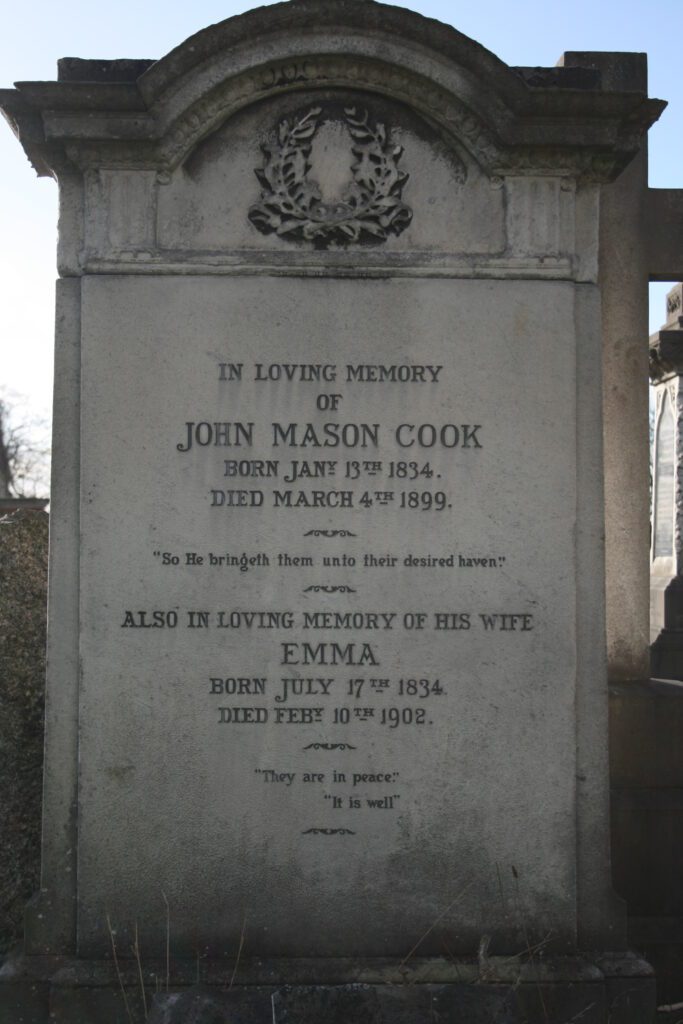

Elsewhere in the cemetery is the grave of John Jason Cook who took over the firm from his father.

But as the growth of online booking rendered their high street travel agents redundant, and low-cost airlines undercut their prices, Thomas Cook’s agency went into liquidation in 2019 after 178 years of trading. The repatriation of the 155,000 people on Thomas Cook holidays abroad was described by one newspaper, with technical accuracy but more than an element of hyperbole, as “Britain’s biggest peacetime repatriation.”

Yet travel and tourism live on and embracing my suitcase and the spirit of Thomas Cook I am taking a holiday. The blog will be back on 24th of June. And if you have free time over the summer, Leicester, The Birthplace of Tourism, merits a visit… and it has more than Ten Interesting Things to See.