I have never shared the view that cemeteries are gloomy places but will allow that they may be tinged with sadness. In the Northern Maramures region of Romania however is a cemetery like no other: The Merry Cemetery (Cimitir Vesel) at Sapanta. Here the celebration of life takes precedence over the grief of death, and death itself is no solemn affair.

The Dacian Culture may have inspired these attitudes. Dacians, early inhabitants of these lands, believed in the immortality of the soul and for them the moment of death was one of exaltation, filled with supreme happiness in anticipation of a better life. Herodotus describes how the Dacians were fearless in battle and joyful when dying, going laughing to their graves to meet their god, Zalmoxis.

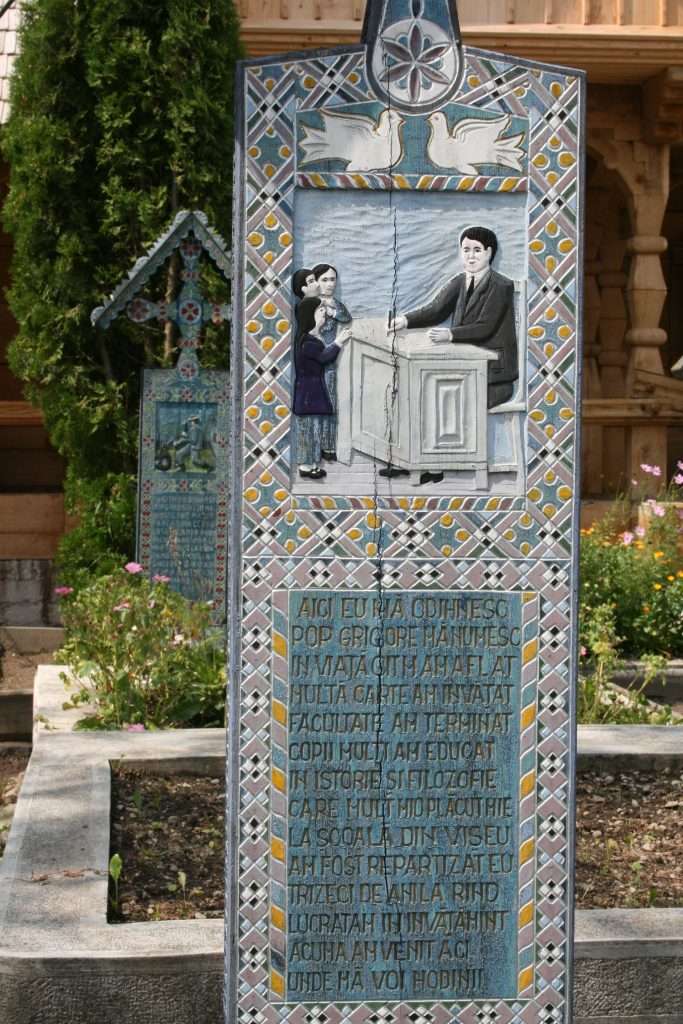

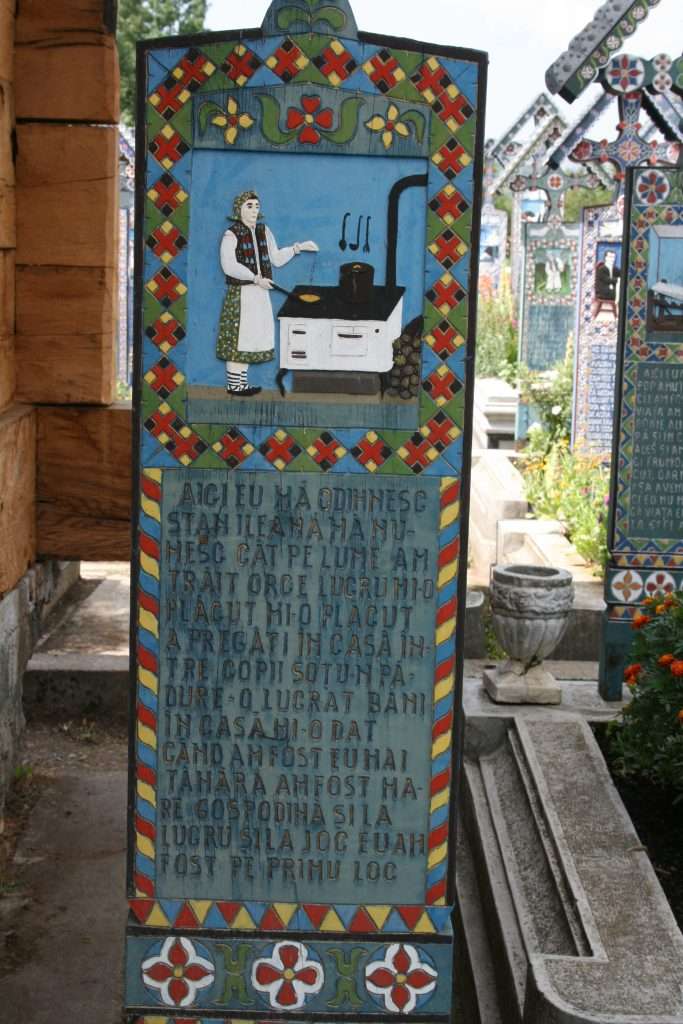

The forest of oak headstones in the Sapanta cemetery is the work of the wood carver Stan Ion Patras. Between 1935 and his death in 1977 he carved over eight hundred commemorative tablets, including his own. He painted these singular memorials in vivid, symbolic colours. Predominant is the radiant, deep “Sapanta blue” speaking of the sky, hope, freedom. Green represents life, yellow fertilility, red passion, and black death.White doves symbolise the soul and a blackbird hints at a suspicious death.

On the grave markers Patras carved portraits of the occupants and naive pictures recording their occupations.

There is a distinctly gendered division of labour:

Below the painted carvings Patras inscribed epitaphs, written in the first person, enabling the inhabitants of the graves to tell the stories of their lives. Far from lauding them or whitewashing them with virtues, the whimsical, witty doggerel records indiscretions, shortcomings, weaknesses, faults, foibles, flaws, failings, and infidelities with cheerful insouciance. Even the modes of death, drowning, drinking, and a disproportionate number of car accidents, provide a source of humour. And the soul who was murdered and buried without his head fails to disrupt the prevailing merriment:

Yet even in Sapanta I found one grave which broke with the relentless good cheer. The speaking poem of a three-year-old girl killed by a taxi read:

May you burn in hell

Taxi driver from Sibiu!

In all of Romania

You could find no other place

But here, near our house

To stop and hit me

And bring grief to my parents.

For as long as they live they will weep for me.

But habitually the latter day Dacians continue to greet death with equanimity; Patras’ apprentice, Dumitru PopTincu, continues his master’s work, and the burgeoning cemetery cocks a defiant snook at mortality.