My English teacher had been at the opening night of John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger at the Royal Court Theatre in 1956, and more than a decade later conjured for us the consternation of the audience when the curtain rose on a squalid flat and its slovenly inhabitants.

Beyond the classical canon, British theatre audiences were used to the escapism of the so-called “well-made plays,” genteel country house dramas from the pens of Noel Coward and Terence Rattigan. On stage a tastefully furnished drawing room would open via French windows onto a garden beyond, and cut-glass accents would deliver brittle, witty dialogue punctuated by pauses for audience appreciation.

Kitchen Sink Painters like Osborne’s contemporary, John Bratby, had already brought a new category of social realism to art, celebrating the everyday lives of ordinary people. Their canvases featured shabby prams parked in overgrown gardens; washing hanging in backyards surrounded by broken bicycles, chairs, and discarded beer bottles; wretched kitchens with chip friers, overflowing rubbish bins, and, of course, grimy kitchen sinks.

Osborne was the first of the Angry Young Men who brought working class anti-heroes to the stage in the late fifties and early sixties. The Kitchen Sink Dramas, located in cramped, low income, domestic environments, addressed issues of alienation, provincial boredom, alcohol abuse, crime, adultery, pre-marital sex, and abortion. They brought regional accents to the stage, and a radical, anarchic howl of rage against middle class privilege and a smug, autocratic Establishment.

Reviews of Look Back in Anger were mixed. The majority disliked Osborne’s play and dubbed it a failure, but notable exceptions were the theatre critics Kenneth Tynan and Harold Hobson. Tynan, whose vitriolic reviews had castigated what he dubbed the Loamshire plays of Rattigan and Coward, eulogised Osborne’s work:

I doubt if I could love anyone who did not wish to see Look Back in Anger. It is the best young play of its decade.

His fervour proved prescient; the play transferred successfully, and a film version followed. When I first saw a production in the 1960s, I was enthralled, fascinated by every detail; still today I seldom contemplate a pile of ironing without remembering Jimmy Porter and Alison.

Osborne’s success continued with The Entertainer (1957). Again premiered at the Royal Court, it was a more overtly political play set against the background of the Suez crisis. The dying music hall tradition, eclipsed by rock and roll, cinema, and television, mirrored the declining influence of the British Empire supplanted by the growing ambit of the USA. Laurence Olivier played Archie Rice, the bitter, failing music hall performer, a role he repeated in the film version in 1960.

More successes followed for Osborne with Luther (1961), Inadmissible Evidence (1964) and A Patriot for Me (1965).

But by the 70s Osborne had abandoned his early socialism, impassioned attacks on the monarchy, and support for CND, espousing instead conservative prejudices, bigotry, and nostalgia, even supporting Enoch Powell. He wrote for the right-wing Spectator and moved to the Shropshire countryside where he played the role of country gentleman. Returning to the Church of England and becoming a drum-beater for Anglican ritual, he approximated to a blimpish caricature of one of the stereotypes in the despised Loamshire plays.

Hindsight is a cheap skill, but looking back at Osborne’s work it seems obvious now that the conservative strain was there from the beginning. Look Back in Anger is largely autobiographical; Osborne’s alter ego Jimmy Porter is angry, but his anger is not that of constructive, political protest, but rather a whining, shouty, resentful outpouring of bile directed against a world which does not provide him with the opportunities and rewards he feels are his right.

When the play was revived at The Almeida last year, I reread it but decided not to see it again. It is a misogynistic rant. Where I remembered working class rage, I found toxic masculinity, dated and unpalatable. His autobiography reveals him in an equally sour light: vicious in his attitude towards his mother and his daughter whom he threw out when she was only seventeen; abusive towards four of his five wives- although, in fairness, they seemed able to reciprocate- jealous of their successes and presuming that they should give up their own work to tend to his needs.

Of course, Osborne was not alone in his misogyny; an unsubtle clue to the ubiquity of that persuasion in the 50s and 60s lies in the genre designation Angry Young Men. Apart from Shelagh Delaney’s A Taste of Honey and Nell Dunn’s Up the Junction and Poor Cow, the writing of angry young women was not visible.

And yet, although his repugnant attitudes are dated, and his writing sometimes shrill, Osborne can also be witty, perceptive, and clever, and the audience shock when the curtain went up on that first production at the Royal Court was one of the defining moments of twentieth century theatre. Moreover, his early kitchen sink realism opened the way for other working-class dramas, novels, films, and television. Those of us who grew up in the sixties still remember the high quality of ITV’s Armchair Theatre and the BBC’s Wednesday Play: who will ever forget Jeremy Sandford’s Cathy Come Home directed by Ken Loach?

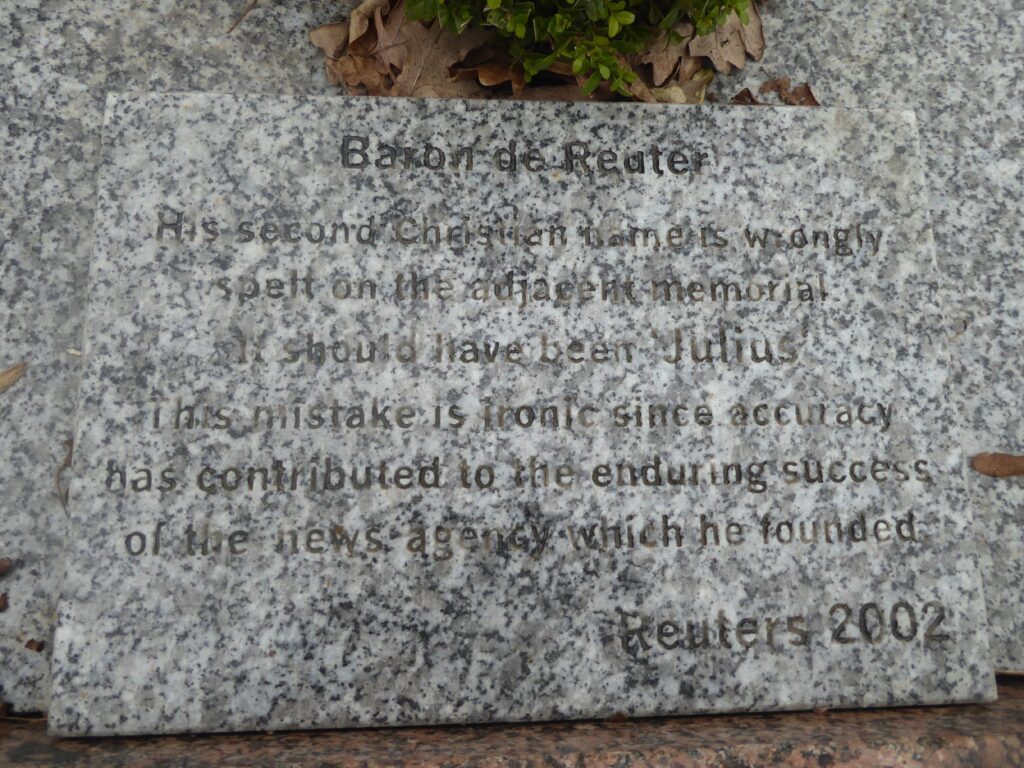

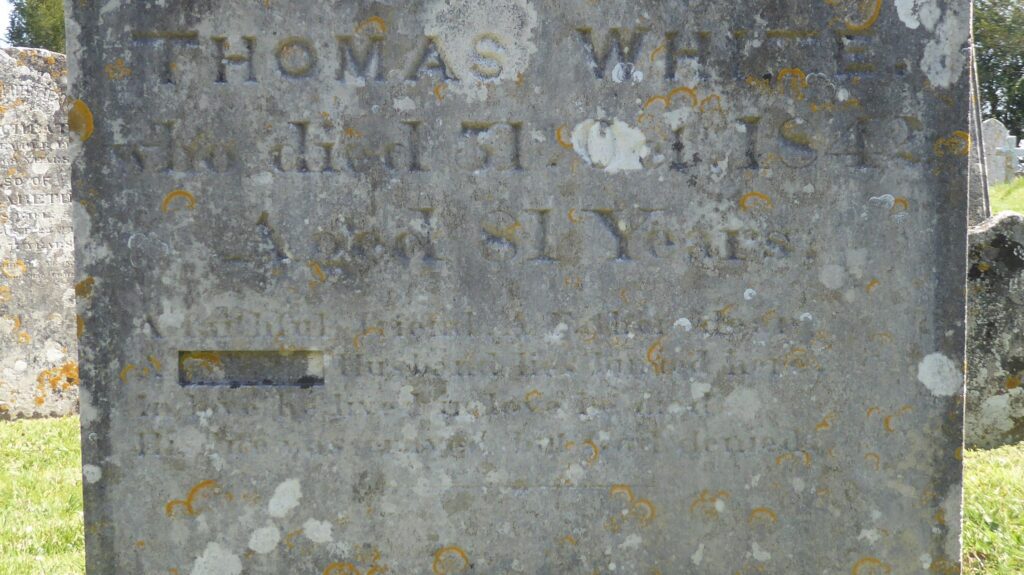

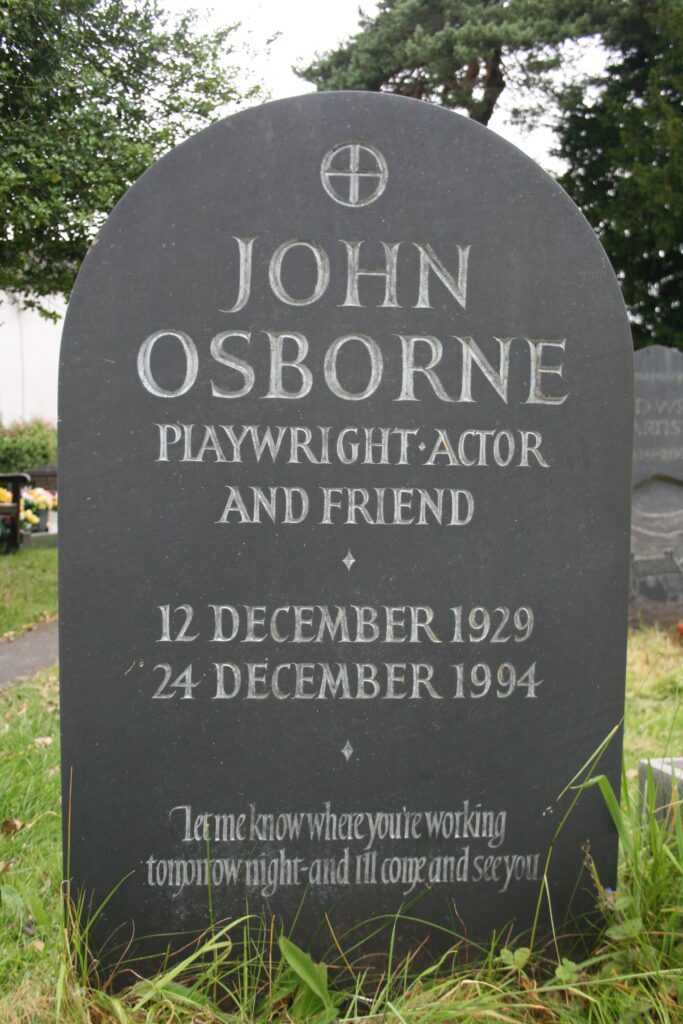

Osborne is buried in St. George’s churchyard in the village of Clun in Shropshire beside his fifth wife Helen Dawson. The quotation on his grave

Let me know where you’re working tomorrow night – and I’ll come and see you

is spoken by Archie Rice in The Entertainer. It is his final interaction with the audience before leaving the stage, and as well as a farewell, I suspect it carries the unspoken, bitter question, “do you think you could have done any better?”

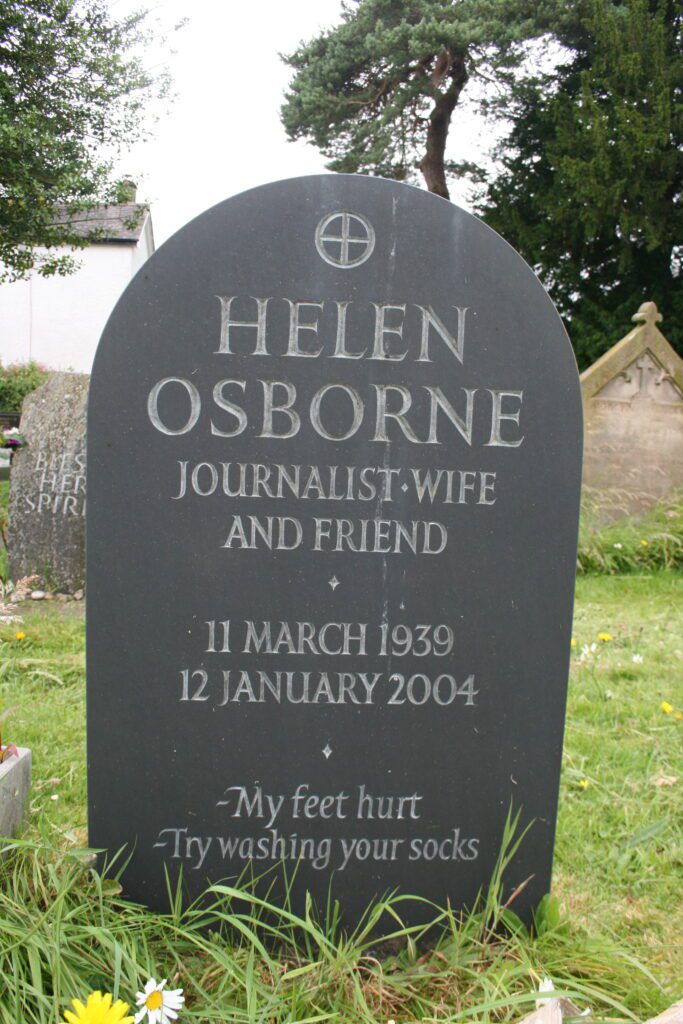

The quotation on Helen Osborne’s grave

-My feet hurt

-Try washing your socks

is an exchange between Cliff and Jimmy in Look Back in Anger. Helen Dawson had chosen a copy of the play as a literary prize when she was in school. When she married Osborne she gave it to him, inscribed, “And back to you.” I have no idea of the significance of the particular quotation, although it does sound like an expression of the disdain which both Osbornes could exercise towards other people.

But they are, undeniably, an attractive pair of graves.