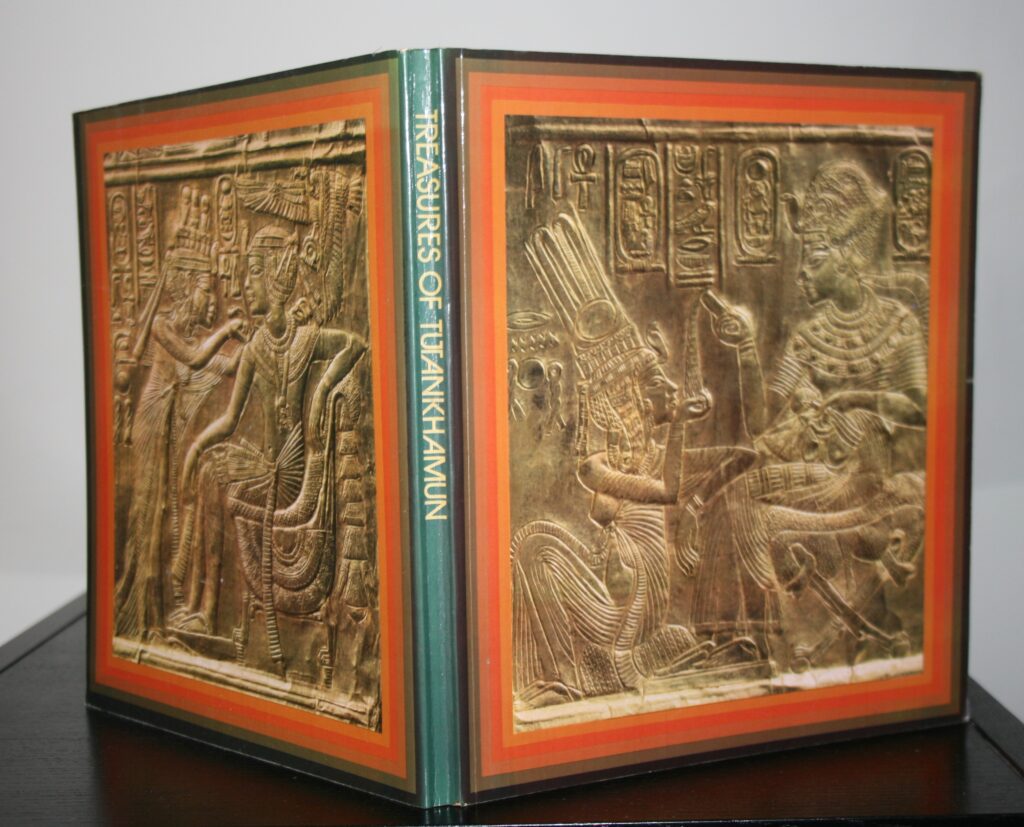

In the early Spring of 1972, I queued for five chilly hours to see the Treasures of Tutankhamun at the British Museum. Over nine months 1.6 million people visited the exhibition, and it remains the most popular in the history of the museum. It was magical. The now famous words of Howard Carter when he first peered into the tomb welcomed us:

…as my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room within emerged slowly from the mist, strange animals, statues, and gold – everywhere the glint of gold. For the moment – an eternity it must have seemed to the others standing by – I was struck dumb with amazement, and when Lord Carnarvon, unable to stand the suspense any longer, inquired anxiously, “Can you see anything?” it was all I could do to get out the words, “Yes, wonderful things.”

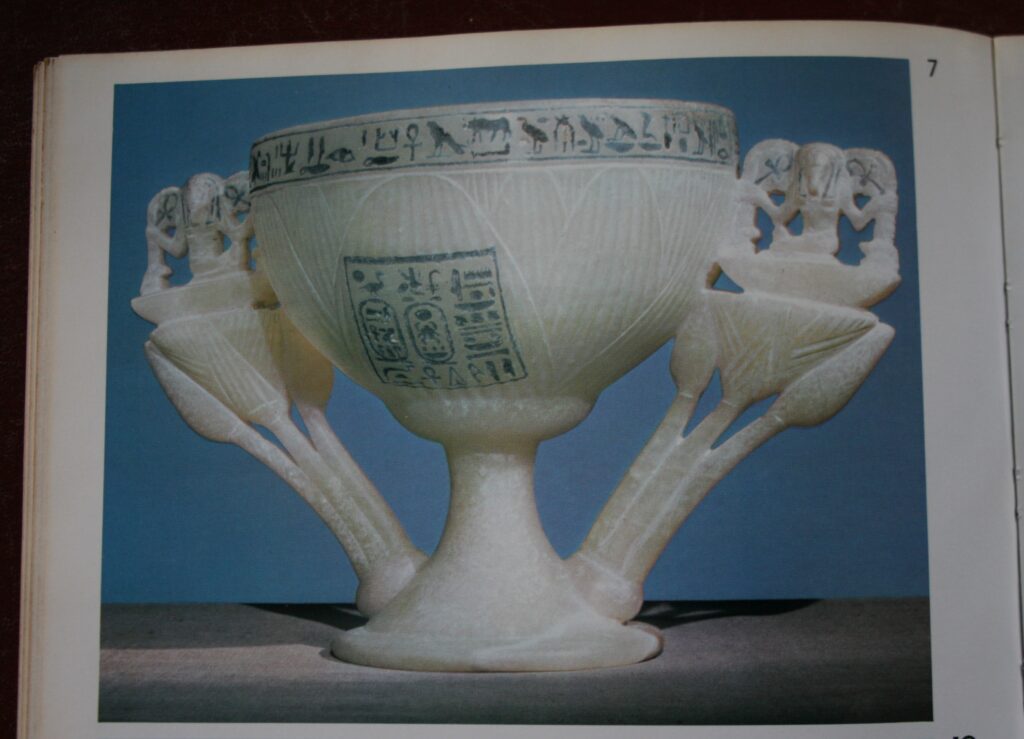

Wonderful things indeed: a gold figure of Tutankhamun, the golden shrine, scarab necklaces and bracelets, alabaster vessels and caskets, and the mask of solid gold, beaten and burnished, which had covered the head and shoulders of the Pharoah. I had stepped out of the grey London streets and into all the colour and spectacle of Ancient Egypt.

Yet whilst I was entranced by these riches I could not shake off the uneasy knowledge that Howard Carter and his financial backer, Lord Carnarvon, were essentially grave robbing, albeit with official sanction. No surprise then that when Carnarvon died in April 1923, only months after the discovery of the tomb, speculation began about “the curse of Tutankhamun.” The apocryphal story of the warning found on the wall of the burial chamber, “Death will come swiftly to those who disturb the tomb of the King,” passed into popular culture.

Carnarvon, of course, died not from a curse but from an infected mosquito bite. Nonetheless his death and that of others with even the most tenuous connections to the excavation were claimed as evidence of the malediction. The list included: George Jay Gould who had visited the tomb and died of pneumonia a few months later; Carnarvon’s brother, Aubrey Herbert, who, five months after Carnarvon’s own death, died from sepsis following dental surgery; Aaron Ember, Egyptologist, and friend of Carnarvon who died when his house burnt down; and Archibald Reid who died soon after x-raying the contents of the tomb.

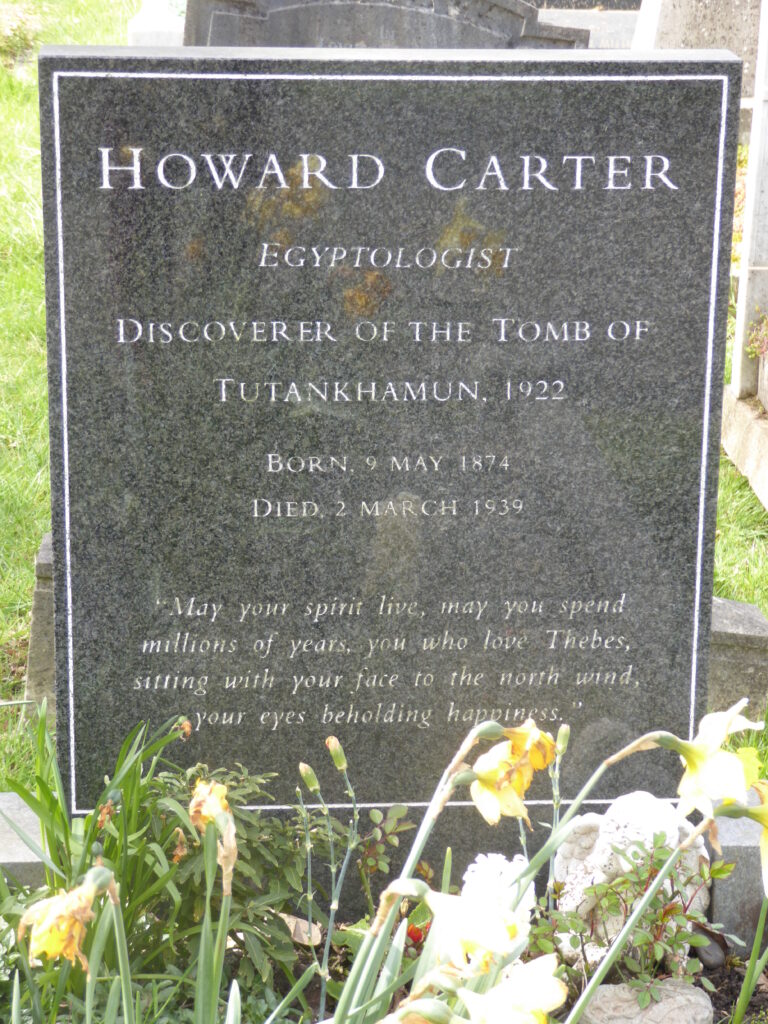

But Howard Carter himself, openly sceptical of the curse, lived on until 1932 when he died of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Despite the drama and glamour of his discovery his fame had dissipated and only nine people attended his funeral. Since that exhibition back in 1972 however his star has risen again and today his own grave in Putney Vale Cemetery in London is carefully tended. The stone bears an inscription taken from the alabaster lotus chalice found in Tutankhamun’s tomb:

May your spirit live, may you spend

millions of years, you who love Thebes,

sitting with your face to the north wind,

your eyes beholding happiness.

And at the foot of the grave an extract from the prayer of the goddess Nut :

O night spread thy wings over me

as the imperishable stars.

Carnarvon’s grave lies within the fortifications of Beacon Hill Camp overlooking his family seat at Highclere in Hampshire. It is surrounded by an ugly iron fence with a padlocked gate.His epitaph

5th EARL OF CARNARVON

DISCOVERER OF THE TOMB OF

KING TUTANKHAMUN

NOVEMBER 1922

IN COLLABORATION WITH HOWARD CARTER

is less than modest given his lack of enthusiasm for the dig, which he had only agreed to finance for one more season in response to an impassioned plea from Carter, and that he only arrived from England after Carter had discovered the entrance to the tomb.

More than twenty years after I saw the exhibition in the British Museum, I viewed those treasures again, this time in the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities in Cairo. There were no queues, only fragile vitrines came between me and the precious objects, and for most of the time I had the rooms to myself with just an occasional group passing swiftly through like a murmuration of starlings. But while the artefacts were as wondrous as ever, and the opportunity to view them almost in solitude an unexpected privilege, the old museum, built in Tahrir Square in 1901, was looking dusty and tired, unworthy of the glorious heritage which it sheltered.

Then in 2003, following an international architectural competition, the Irish practice Heneghan Peng won the contract to design a new museum to be built on the Giza Plateau next to the pyramids. Work on the site halted during the conflict which followed the Arab Spring of 2011 and during this time rioters broke into the old museum, the destruction and damage including two statues of Tutankhamun. And in events far worse than any imagined curse the museum was reportedly used as a torture site.

But work resumed on the new Grand Egyptian Museum in 2014, and it is due to open later this year. For the first time Tutankhamun’s entire treasure collection will be on display – and in the exact order in which Howard Carter found the objects in the tomb. More than five million people are expected to visit every year, and for all my reservations about grave robbing I will be among them.