Whitchurch Canonicorum lies only a few miles from Charmouth and Lyme Regis, but while holiday crowds hug the Dorset coast the tiny inland village remains undisturbed.

It was not always so, for the church of St. Candida and the Holy Cross was once a busy and prosperous centre of pilgrimage. Today it houses the only British shrine with relics, apart from that of Edward the Confessor in Westminster Abbey, to have survived the Reformation. The simplicity of the tomb concealed its true purpose and, mistaken for an ordinary grave, it escaped destruction.

St. Candida, or Saint Wite, was a Saxon holy woman, an anchoress purportedly martyred in 831 when 15,000 Danes landed at Charmouth and engaged in widespread slaughter. In the church a thirteenth century marble tomb chest contains her relics. When the chest cracked open in 1899-1900, a lead reliquary was found inside. It contained the bones of a forty-year-old woman and bore the inscription “HIC REQUECT RLIQE SCE-WITE” (Here rest the remains of Saint Wite) on the lid. The stone beneath the tomb contains three vesica-shaped openings where pilgrims left offerings of coins, candles, cakes, and cheeses. More dramatically they inserted diseased limbs or, with a little struggle, their whole bodies, into the vesica to ensure the closest possible contact with the relics. When the cure was successful they made candles, the length and breadth of the previously afflicted part, which burned around the shrine. Suspended above it hung their discarded crutches and sticks.

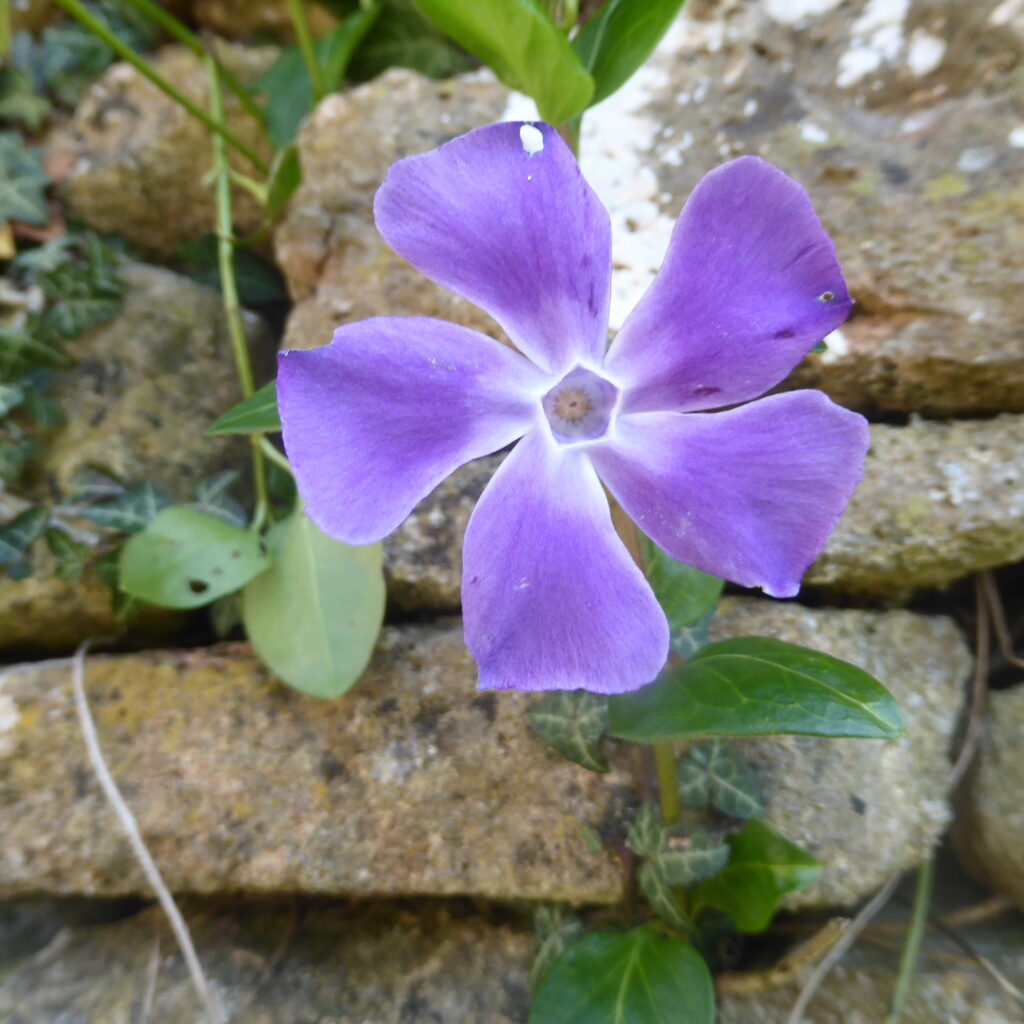

A mile to the south of the church lay St. Wite’s well where the saint lived and prayed and maintained fires as beacons for sailors. The pure waters of the well were reputed to heal eye diseases. The wild periwinkles which bloom in the area at this time of year are still known as “St. Candida’s Eyes.”

Also in the church, buried beneath the floor of the now vestry, are the remains of John Somers. Following a shipwreck, this privateer started a colony and became governor of The Somers Isles, later Bermuda. His life as a castaway allegedly provided the inspiration for Shakespeare’s play The Tempest. When he died, of “a surfeit in eating of a pig,” his heart was buried in The Somers Isles, but his body, pickled in a barrel, was landed at the Cobb in Lyme Regis, and returned thence to Whitchurch Canonicorum .

But I had not come in search of either of these luminaries. I was on the trail of a Bulgarian dissident killed by the Bulgarian secret service in cooperation with the KGB in 1978. Georgi Markov had been a successful writer in Bulgaria, winning literary prizes, part of the official intelligentsia, associating with high-ranking politicians, and enjoying an affluent lifestyle, including driving a silver BMW. Indeed, Zhivkov, the Party leader, had tried to lure him, with offers of more privileges and positions, into serving the authorities through his writing. But instead, his work had become more critical and satirical in relation to the regime. He came under increased scrutiny and some of his works were banned. In 1969 he defected to Italy and in 1970 moved to England, where from 1975-1978 he was employed by the BBC World Service and by Radio Free Europe. Increasingly he used these organs, especially his broadcast In Absentia for RFE, to criticise the Communist government in Bulgaria, and to accuse Zhivkov of fraud, nepotism, incompetence, mediocrity.

Then, in September 1978 came a drama which we would previously have associated only with the novels of Le Carré and the dark, mysterious streets of those Eastern European cities which lay beyond The Iron Curtain. Markov had left work at Bush House and was waiting at a bus stop in The Strand near Waterloo Bridge for the bus home to south London. In this most mundane of circumstances and humdrum of environments a man bumped into him and with the tip of his umbrella pushed a sugar-coated ricin pellet into his leg. As the sugar dissolved the poison was released into his bloodstream. The man disappeared in a taxi and that evening Markov was admitted to hospital with a fever and died there four days later. Medical staff had been sceptical of his claims that he had been poisoned but Scotland Yard, aware that there had been two previous attempts on Markov’s life, ordered an autopsy and the remains of the poisoned pellet were discovered. To test the theory, they injected a pig with the toxin. After suffering identical symptoms to Markov, the pig died two days later.

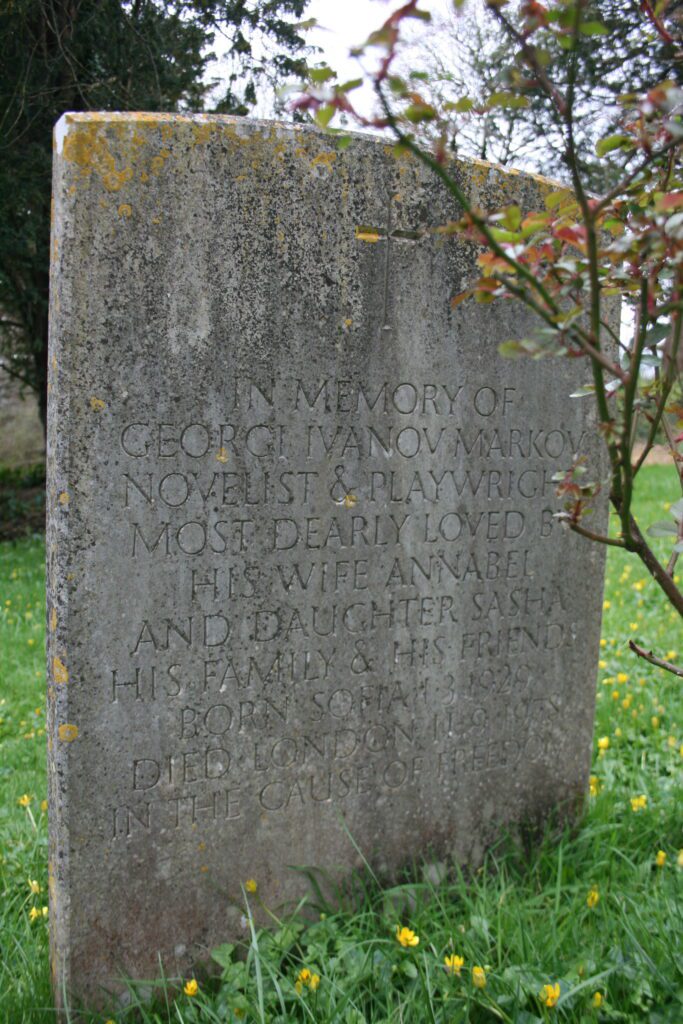

Markov’s stone in the churchyard at Whitchurch Canonicorum records his death “in the cause of freedom” in English on one side and Cyrillic on the other.

No one was ever arrested for the killing but suspicion fell on the Italian born Bulgarian agent Francesco Gullino. The latter had been arrested for smuggling in Bulgaria in 1970 and offered a choice between prison and espionage work. His file in the Bulgarian archives records his training and missions but pages relating to the time of Markov’s killing are missing, however one of his fake passports shows that he was in London at the time of the murder. In 1993 British authorities interviewed him based on information from Bulgaria but no arrest was made. He remained free until his death in 2021 leaving the suspicion that he may have given evidence on other cases in return for his freedom.

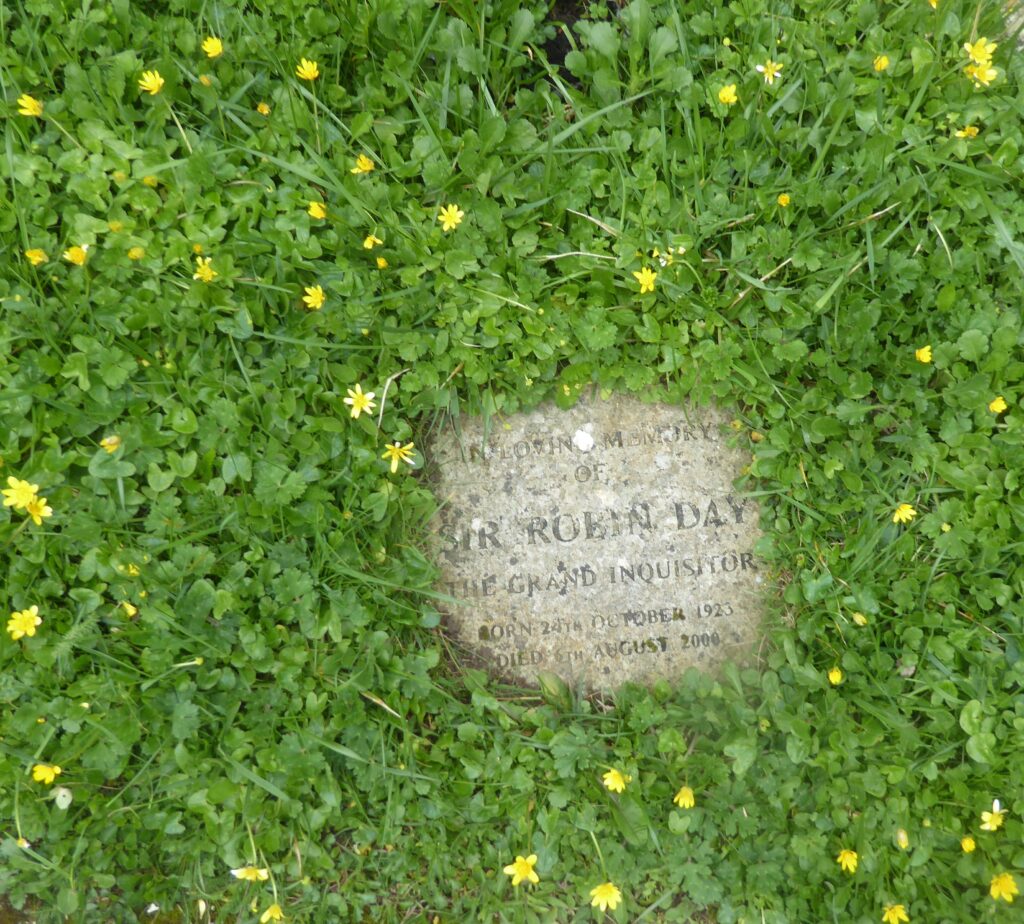

About to leave the churchyard I spotted another small, flat stone dating from 2000 and bearing the legend “The Grand Inquisitor.” Here were the ashes of Robin Day, the television journalist credited with inventing the political interview on television. I remember him as a staid, conservative figure, uncritical of government and traditional institutions like monarchy and the legal profession, one who accepted a knighthood, and was chummy rather than subversive in his interviews with politicians. In the 1950s however Day had been the first to break with the habitual deference which journalists had previously shown when interviewing members of the establishment. At the beginning of his career, he was criticised for being disrespectful and pugnacious towards his subjects. His incisive, abrasive style was turned first against Kenneth Clarke then chairman of Independent Television and thus his employer. Later he interviewed President Nasser after the 1956 Suez crisis, and ex-president Truman: “Mr. President do you regret having authorised the dropping of the atomic bomb?” he asked. His less than respectful 1958 interview with then Prime Minister Harold MacMillan was described by the Daily Express as “the most vigorous cross examination a prime minister has been subjected to in public”. Hence he became known in British broadcasting as “The Grand Inquisitor.”

I wonder how they rub along: the anchoress, the privateer, the dissident writer, and the journalist. They surely have a wealth of stories to share as they lie together now in the quiet of Whitchurch Canonicorum.