The woman crouched beside the white grave marker was Australian. The name on the stone was of a much younger man. “He would have been my great uncle,” she explained. “No one from my family has ever been able to come before. I am the first one to visit him.” She planted a poppy cross and a small Australian flag beside the grave, remained with him for a while, and took photographs for her family. None of those still living had ever met him, he never had a wife or children of his own, his nieces and nephews had been born after his death, but they knew that he had been killed in action at Messines Ridge and they knew exactly where his grave lay in Kandahar Farm Cemetery.

More than 416,000 young men from Australia enlisted in the First World War. They travelled more than 9,000 miles from home to serve on the Western Front, at Gallipoli, and in the Middle East. 60,000 of them died.

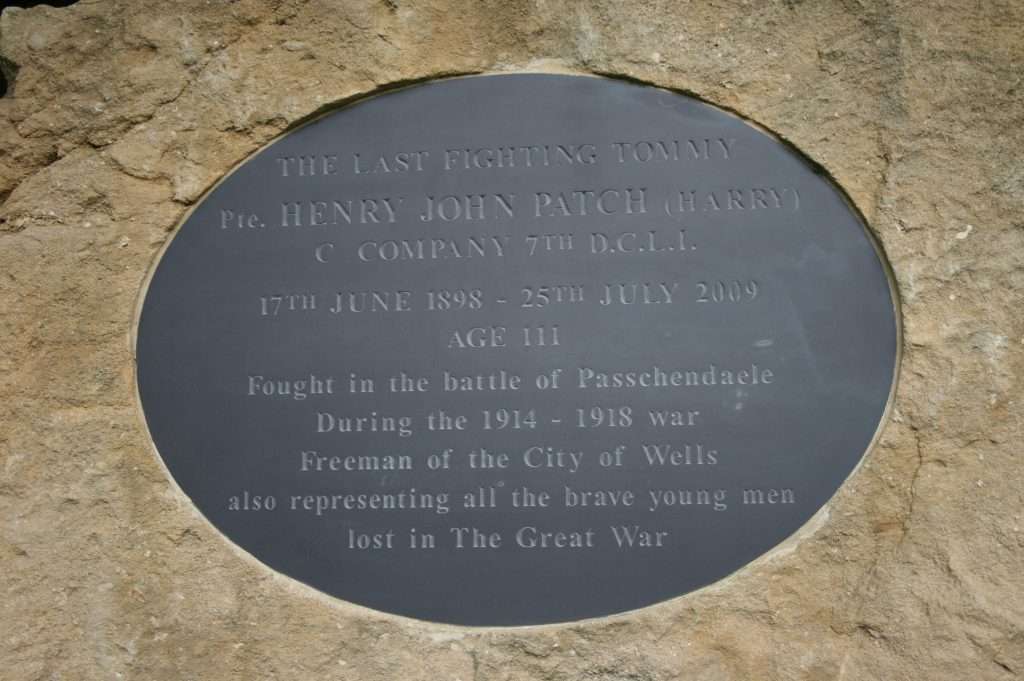

The tragedy of war is often dressed up as something glorious, a great cause, bolstered by jingoism and propaganda, so that names like Agincourt and Mafeking, Waterloo and Trafalgar, remote events, worm their way into the national psyche carrying a certain glamour, obscuring the horror that lies behind them. But the First World War was something different. No one speaks of Passchendaele, the Somme, or Gallipoli in anything but sombre tones.

Technological advances in warfare – the use of submarines, aeroplanes, poison gas, machine guns, artillery shells – distinguished this from previous conflicts. Earlier wars had been the business of professional armies, but this time conscription increased the scale of the slaughter. Estimates put the number of civilian and military casualties at forty million, between fifteen and twenty-two million deaths, and twenty-three million wounded. Over four years, deaths came from injuries, from starvation, and from disease, from tetanus, gas gangrene and the influenza pandemic.

Yet despite the carnage and chaos of that war the lady from Australia was able to find her great uncle’s grave without difficulty.

In previous wars the bodies of wealthy, aristocratic and upper middle-class officers had been shipped home, where monuments and statues were raised above them. Those of ordinary soldiers were buried haphazardly and anonymously, or left to rot. At Waterloo scavengers pillaged from the dead, selling relics to visitors. Burials were in shallow pits and when the bodies proved too many and the stench too great, they were burned. Later their bones were dug up and used to filter sugar or ground up for use as fertiliser. It might have been the same in this war were it not for Fabian Ware.

Before the war Fabian Ware (1869-1949) had been a schoolmaster, inspector of schools, examiner for the civil service, a journalist and editor. In 1914, when war broke out, he attempted to join the British Army, but at forty-five he was deemed too old for active service, and instead joined a mobile ambulance unit working for the British Red Cross. There was at this time no official system for recording burials. Individual soldiers were attempting to mark the graves of their fallen comrades, but the graves were often lost as another battle raged, the markers disappeared, and those who remembered their location were themselves killed. At the same time the Red Cross was overwhelmed with queries regarding the whereabouts of burial places. Ware began to make notes on the location of graves and persuaded the Red Cross to fund more durable markers. By 1916 the organisation had sent 12,000 photographs of graves marked with wooden crosses to the men’s families.

Understanding that families and friends would want to visit the graves after the war, Fabian Ware extended and formalised his work with the establishment of a special unit, the Army Department of Graves and Enquiries, to mark and record the location of the graves of all soldiers from Britain and the Dominions, not just on the western front in France and Belgium, but in all the theatres of war. The task of course was impossible, in the violence and turmoil of war many bodies went unburied.

But the breadth of Ware’s work was extraordinary. He negotiated with every country where British and Commonwealth soldiers died to obtain land in perpetuity for cemeteries. He raised money to buy the land. Not only did he succeed in France and Belgium, in Italy, Serbia, Greece and Egypt, but even in Gallipoli, a sensitive task since Britain had invaded Turkey.

Ware was committed to the principle that officers and men should be buried side by side, that all ranks should be treated equally, and that there should be no distinction of race or religion. These moral standards were not easily effected.

When Will Gladstone, grandson of the former Prime Minister, was killed in France his family had his body exhumed and shipped home, notwithstanding a ban on exhumations because of health hazards. Ware pushed for the ban to be enforced more strictly not only because of the sanitation issues but also because he believed that there should be fellowship and equality in death. Since very few of the bereaved families could afford the cost of repatriation, Ware determined that no more bodies should be returned. His democratic ideals led him into conflict with aristocrats used to their own wishes prevailing. Princess Beatrice claimed that it dishonoured “a hero of the royal blood” (her son) to bury him alongside others. The Countess of Selbourne declared that “This conscription of bodies is worthy of Lenin.” Twenty-seven further bodies were returned to Britain, but most families abided by the rules.

In 1917, under the direction of Ware, the Imperial War Graves Commission (later the Commonwealth War Graves Commission) was established, to ensure the care of the graves after the war. Ware began collaborating with a team of architects- Edwin Lutyens, Reginald Blomfield, and Herbert Baker – to design more permanent memorials to replace the wooden crosses in the cemeteries. These new grave markers were to be of a uniform design, chosen to accommodate those of all faiths and none. Each simple white Portland stone bore the man’s name, rank, army number, regiment, and date of death. When it was not possible to identify the body, the wording read “A soldier of the Great War known unto God.”

The Commission worked with meticulous attention to detail: the top of each stone was curved to allow rainwater to run off; the planting schemes around the graves were the work of Gertrude Jekyll, with a floribunda rose, the Remembrance Rose, set to the side of each stone, and low growing herbaceous plants to the front so that the inscriptions were not obscured, and soil splashback was prevented when it rained.

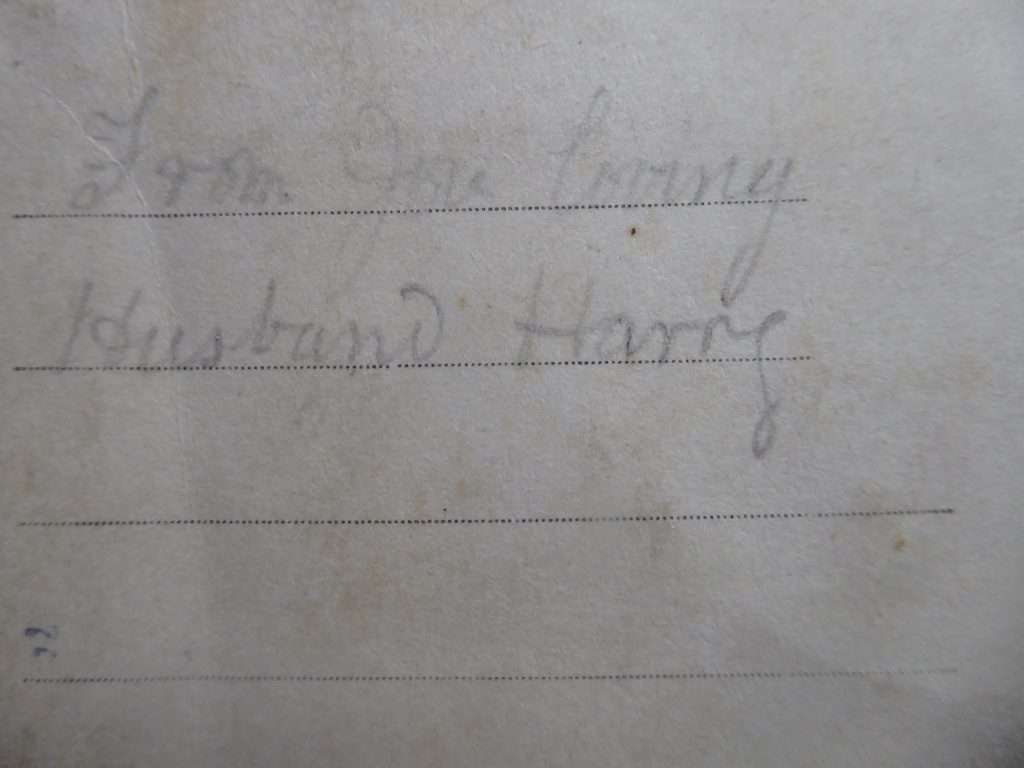

An appropriate religious symbol might be engraved on the stone if desired, and families could choose a personal epitaph to a maximum of sixty-six words at a cost of three and a half pence per letter. This met with justified criticism for only the relatively wealthy could afford this, and, despite Ware’s democratic ideals, it is noticeable that there are more epitaphs on the graves of officers than on those of ordinary soldiers.

Moreover, the wording of the epitaphs sometimes proved a sensitive issue, and the Commission reserved the right to veto any inflammatory inscriptions likely to cause “political upset.” While most families chose poetry, classical and biblical references, personal tributes, or poignant details – “An only son killed in action on his way to his leave and wedding” – others were more contentious. On the grave of a deserter, Albert Ingham, the inscription, “Shot at dawn, one of the first to enlist, a worthy son of his father,” carried an implied criticism of military commanders and political leaders. It was a deserved reproof, for there had been brutal executions of deserters, suffering from shell shock and mental collapse after seeing their friends slaughtered. Those executed included boys who had lied about their age to join up; one, Herbert Burden, was still too young to have officially joined his regiment when he was shot by a firing squad. But in a country where women were still handing out white feathers to men not in uniform, where there was still fervent militarism, and where deserters were not officially pardoned until 2006, the Commission showed unusual empathy in accepting the epitaph.

Similarly, deviating from the official stance, the representatives of the Commission usually accepted reflections on the futility of war, although, regrettably, they proscribed “A noble son sacrificed for capitalism.” They requested an alternative suggestion from the parents who submitted, “His loving parents curse the Hun.” And while it is impossible not to sympathise with the anger and hurt of the parents, it should be remembered that the Commission’s task was a delicate one, for by this time as well as seeking to commemorate the dead, they were hoping that the graves, in bearing witness to the horror of war, would promote peaceful settlements of future conflicts.

In addition to the individual graves, Lutyens had designed the War Stones or Stones of Remembrance, bearing the wording “Their Name Liveth for Evermore,” for all cemeteries housing 1,000 or more graves. The abstract secular design chosen to be suitable for all denominations, emphasising equality of remembrance, provoked the ire of the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishops of the Church of England who complained that this was a pagan monument and demanded a cross or other Christian symbol in its place. In a patient response that was ill-deserved the Commissioners compromised with the addition of a Cross of Sacrifice, designed by Blomfield, in every cemetery with more than forty graves.

By 1927 there were five hundred cemeteries, by 1937 there were one thousand eight hundred and fifty. The largest is at Tyne Cot near Passchendaele in Belgium, where there are 12,000 graves, more than 8,000 of them unidentified. And away from the battle sites, in church yards in Britain, Canada, USA, India, South Africa, New Zealand, and Australia, Commonwealth graves record the deaths of wounded soldiers after they had been discharged and sent home.

One of the most agonising tasks for the Commission in the aftermath of the war was the continued search for bodies. The front-line areas were searched at least six times, and where there had been particularly intense fighting up to twenty times. Between 1918-21 200,000 bodies were recovered. In 1937 between twenty and thirty were still appearing every week when farmers ploughed their fields. They are still unearthed today: in Belgium there are around fifty reburials each year.

54,896 soldiers who were never found or identified are remembered on the Menin Gate in Ypres, where local buglers sound the Last Post every evening. At Thiepval a memorial commemorates 72,337 men with no known graves who died in the battles of the Somme. A third memorial at Tyne Cot bears a further 34,887 names.

It was always Ware’s hope that the memorials would help people to realise the cost of war and so prevent future wars. He worked with others raising memorials to French and German soldiers, hoping to unite in common remembrance and international understanding. Speaking at annual Remembrance Day ceremonies, he advocated the avoidance of armed conflict as a means of settling international disputes, but stone masons were still at work on the Menin Gate when Germany invaded Belgium in 1940.

Fabian Ware continued his work for the CWGC until a year before his death in 1948 when he resigned due to ill health. He is buried in the churchyard at Amberley in Gloucestershire. His headstone is in the WGC style. Beside a memorial plaque in the church is one of the original wooden grave markers which he brought home and presented to the church. It bears the legend “Unknown British Soldier.”

He inspired the foundation of the

Commonwealth War Graves Commission,

which erected the memorials and maintains the cemeteries

on the battlefields of the First and Second World Wars

The young men who lie in the Commonwealth War Graves and whose names appear on the memorials lost everything: their hopes and ambitions, their dreams, their lives. No one could bring them back, and those who had loved them would never see them again. With the cemeteries and memorials, raised through his compassion and diplomacy, Fabian Ware offered the only comfort he could: the knowledge that those young men did not lie alone and neglected, that they would always be remembered, their graves cared for and waiting, no matter how long it might be until someone came to visit them.

But those acres of white stones failed in their second purpose, for their message of Never Again remains unheeded.