My grandfather, Harry Manley, was the gentlest of men, and I cannot imagine what emotions he confronted and endured when, somewhere on the Western Front, he faced the prospect of killing other men. Like many of his generation he never spoke of the war. He always attended church on Sundays, so he must have attended Remembrance Services. He probably wore a red poppy, but I have no memory of it. All that I knew as a child was that the reason he walked with a limp was because he had been wounded in a long-ago event, referred to by adults, who clearly had neither the inclination nor the intention to discuss it further, as “ the war.” This was strange because “The Second War” was a frequent subject of conversation and featured regularly in heroic films and novels.

The First World War only gradually took shape in my consciousness through History lessons, and English Literature classes where a passionate teacher introduced us to the poems of Wilfred Owen.

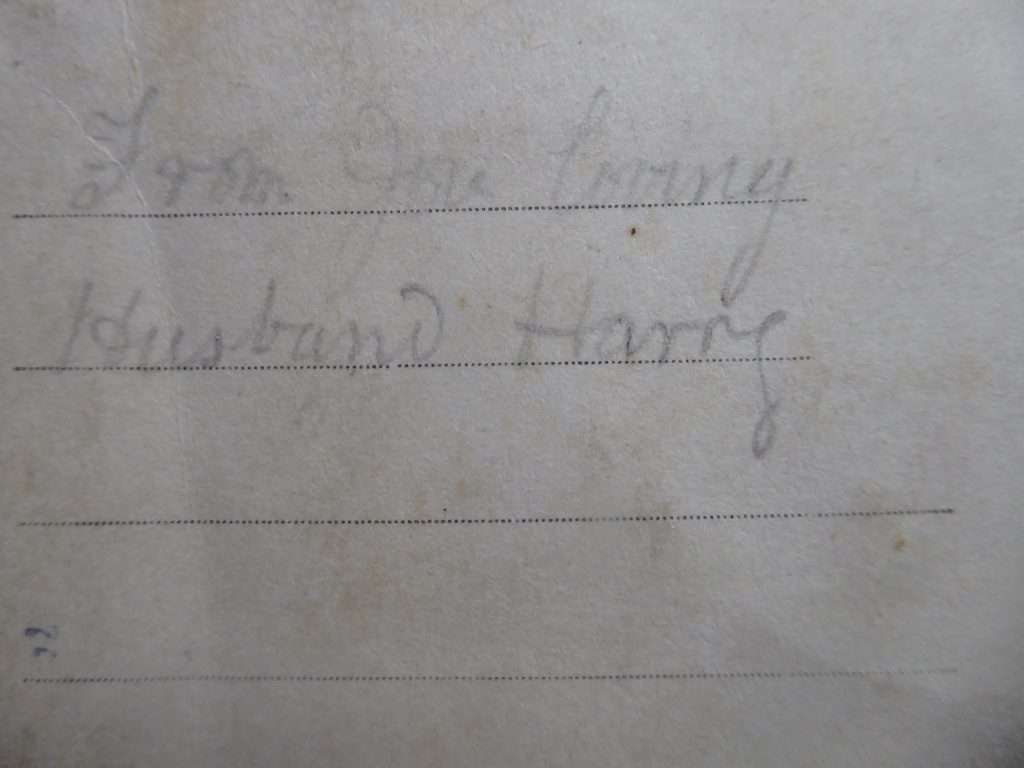

Only in her own last years, when she began to talk a lot about her parents and childhood, did my mother share her own limited knowledge of her father’s experience. Somewhere in France or Belgium he had been wounded and was lying in a shell-hole, unable to move, when a field ambulance arrived. The ambulance was full, and from what I have read of World War I, I would take that description literally. The driver assured my grandfather that he had noted his position and would come back for him. This must have seemed a well-meant but unlikely promise: how would anyone locate one shell hole on a chaotic battlefield; fighting might resume at any time; the ambulance might be blown up and the driver himself killed. But return he did, and my grandfather was duly transferred from a field hospital to a London one. My grandmother was summoned to nurse him: staff shortages or because he was not expected to survive? Either way she arrived with determination, and skills learned in the Cottage Hospital in Ellesmere Port.

My grandfather became one of the lucky ones who not only came home but retained his calm, gentle nature. He resumed his job as a brick layer and my mother was born in 1920. But frequently throughout her childhood, she told me, bits of shrapnel would rise to the surface of my grandfather’s wound and a terrible stench would fill the house. My grandmother, ever stoical, practical, and capable, would calmly remove the offending fragments and clean away the foul stinking pus.

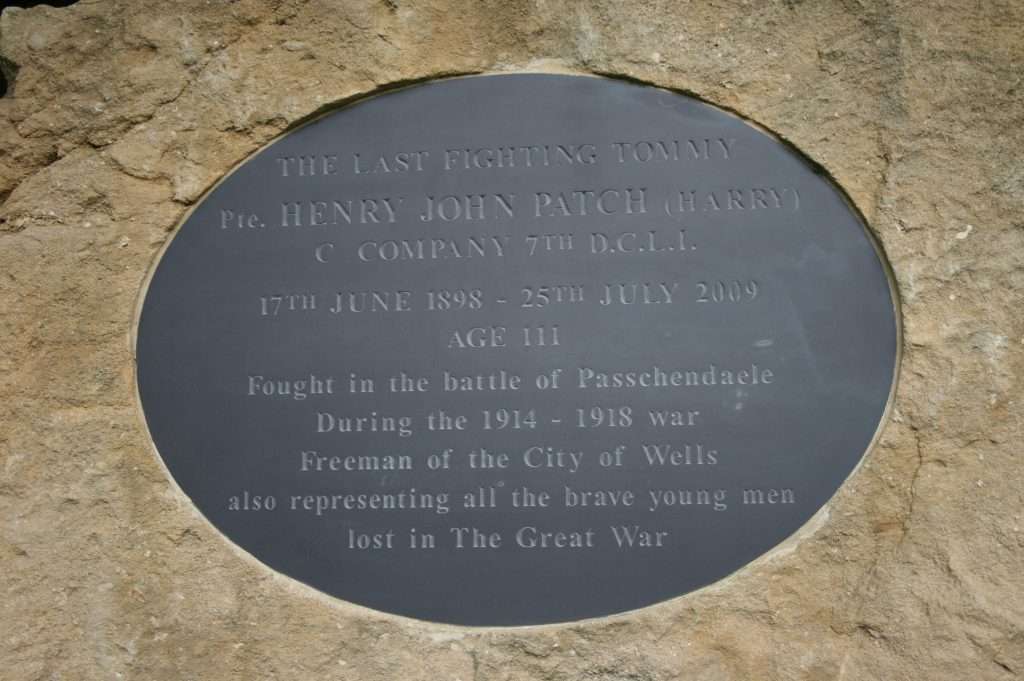

My grandfather died in the 1960s, but another Harry, Harry Patch, lived until 2009, dying at 111, by which time he had found fame as “The Last Fighting Tommy.” Harry Patch refused to speak of the war for eighty years, but in 1998 he broke his silence to recall the terrible loss of so many lives and to assert the futility of war. Five years later he returned to Belgium, for the first time since the war, to lay a wreath in memory of dead friends at the spot where he was wounded, and they were killed. In 2007, his book The Last Fighting Tommy, based on interviews conducted by Richard van Emden, was published.

Harry Patch left no doubt of his reluctance to go to war: “I didn’t want to go and fight anyone, but it was a case of having to…why should I go out and kill somebody I never knew, and for what reason?”1 I could never understand why my country could call me from a peacetime job and train me to go to France and try to kill a man I never knew.”2

Nor was he in any doubt of the consequences of non-participation: “(The officer) had his drawn revolver and I got the distinct impression… that anybody who didn’t “go over” would be shot for cowardice where they stood.”3

He drew a raw picture of the trenches: “the noise, the filth, the uncertainty and the calls for stretcher bearers.”4 “There was no sanitation at all and the place used to stink like hell.”5 “We lived with rats… When you went to sleep you would cover your face with a blanket and feel the damn things run over you.”6 “We were sitting in a sea of shell holes…They were half full of water and one,…well, the stench was terrible, a half-rotting body was in there.”7 “The bodies of wounded men who were dying… would sink out of sight in the morass. They would never be buried.”8 “A lad was ripped open from his shoulder to his waist, and lying in a pool of blood…he looked at us and said “shoot me.””9 “I saw one German… a shell had hit him and all his side and his back were ripped up, and his stomach was out on the floor.”10

Harry and the other members of his Lewis gun team had a pact; “We wouldn’t kill, not if we could help it… We fire short, have them in the legs, or fire over their heads, but not to kill, not unless it’s them or us.”11

On 22nd September 2017 Harry was wounded, the others in his team were killed. Harry wrote, “That day, the day I lost my pals, 22 September 1917 – that is my Remembrance Day, not Armistice Day.”12

Harry’s visceral loathing of the war he was forced to fight resounds from the pages of his book: “At the end of the war , the peace was settled round a table, so why the hell couldn’t they do that at the start, without losing millions of men?”13 “The politicians who took us into the war should have been given the guns and told to settle their differences themselves, instead of organizing nothing better than legalised mass murder.”14 “War,” he averred, “ is a calculated and condoned slaughter of human beings,” and affirmed, “Too many died. War isn’t worth one life.15

Of Remembrance Day, Harry wrote, “For me 11 November is just show business… the Armistice Day celebrations on television…it is nothing but a show of military force…I don’t think there is any actual remembrance except for those who have actually lost somebody they really cared for in either war.”16

Harry Patch was determined not to have a state funeral but, as the last veteran of any nationality who had served in the trenches, he agreed to a public one. His funeral was held in Wells Cathedral with a theme of peace and reconciliation, and, in accordance with his instructions, the soldiers from Belgium, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom who accompanied his coffin were not allowed to carry their ceremonial weapons. A memorial stone beside the Cathedral Green commemorates his life.

But Harry Patch chose to be buried at a private ceremony near the graves of his parents and brothers, in St. Michael’s churchyard in Monkton Combe.

And that is a where I go to remember: Harry Patch; my grandfather, Harry Manley; the other men who came home to live ordinary lives; the millions, mostly young, who lost their lives or health in that pointless war; and their wives, lovers, girlfriends, mothers, sisters, and friends whose lives were forever diminished by their loss.

- Harry Patch with Richard van Emden, The Last Fighting Tommy, Bloomsbury, 2018, p.59.

- Ibid., p.137

- Ibid., p.91

- Ibid., p.74

- Ibid., p.77

- Ibid., pp.104-5

- Ibid., pp 98-9.

- Ibid., p.99

- Ibid., p.94

- Ibid., p.93

- Ibid., p.71

- Ibid., p.203

- Ibid., p.137

- Ibid., pp.188-9

- http://news.bbc.co.uk Veteran, 109, revisits WW I trench.

- Patch, The Last Fighting Tommy, p. 20

https://www.ppu.org.uk The Peace Pledge Union produces white poppies to reassert the original message of remembrance: “never again.” They are a symbol of remembrance of all victims of war, of a to challenge militarism, and of a commitment to peace.

https://www.wri-irg.org War Resisters International is a global network of grassroots antimilitarist and pacifist groups working for a world without war.