I loved the Grandes Dames of Oxford Street. Of course, when I arrived in the city in 1970, I explored Carnaby Street and King’s Road, delighting in the brash, new boutiques with their loud pop music, communal changing rooms, and startlingly rapid turnover of fashions, but it was Oxford Street that captured my heart. The magnificent stately department stores, with their classical and art deco architecture, occupied whole blocks. Though damaged in the war years, they had pieced themselves back together, freshened up, and faced the world with impassive self-assurance. Their ornate entrances bore sculptures above the doors, the window displays rivalled any art gallery, and when you entered the air was heady with the combined scents of the perfume counters.

So confident were these great ladies that they scorned to scrabble after the very commerce which fed them. For they chose to make Saturday their early closing day. Coming from a typical provincial town where Wednesday, dead space in the middle of the week, was early closing day and shops fairly burst with customers on Saturday afternoons, I was astonished. From 1pm on Saturdays until Monday morning, at the very time when potential customers had the freedom to visit and had just received their weekly pay packets, dignified, superior Oxford Street chose to close its doors, and the normally thronged pavements grew quiet.

The very names of these unruffled purveyors of finery filled me with delight: Marshall and Snellgrove; Bourne and Hollingsworth; DH Evans; Selfridges; John Lewis; but the one I loved best was Peter Robinson. This magical store situated on the north-east segment of Oxford Circus, stretching east along Oxford Street and north into Regent Street, lay at the very beating heart of the twentieth century agora. Its eponymous founder, a farmer’s son from Yorkshire, had opened a drapery shop in 1833. In 1840 he established a second store in Regent Street: The Court and General Mourning House Store, aka “Black Peter Robinson’s.” There he kept a coach permanently parked outside with a black clad coachman and two lady fitters, similarly attired, seated inside, ready to speed to the home of any recently bereaved widow.

In 1850 Peter Robinson expanded his Oxford Street drapery to sell ladies’ clothes and accessories. During that decade he promoted one of his drapery assistants to the position of silk buyer and in 1864 offered him a partnership, but John Lewis preferred to open his own Oxford Street premises.

Peter Robinson died in 1874 leaving the Regent Street branch to his eldest son Joseph and the Oxford Street store to his second son, John Peter. The latter bought out his brother in 1895. As fashions and social attitudes changed Black Peter Robinson’s declined while the Oxford street shop flourished. But when John Peter died none of his children wanted to take on the running of their inheritance and it became a limited company, “run by accountants” in the scornful words of Gordon Selfridge.

But Selfridge was unfair, for Peter Robinson’s went from strength to strength; when Burton’s Tailoring, the most successful menswear store of the day, bought up the company in 1946, they not only retained the name but opened more branches alongside their own businesses. And in 1965, in the Oxford Circus basement, they opened Top Shop. This was an inspired move with Top Shop rivalling the upstart boutiques by catering specifically for the under twenty-fives, while the main store continued to serve its older clientele. The buyers employed by Top Shop in the ensuing years were peerless, all with a consummate eye for fashion.

During my first term in London, I bought two long-cherished garments at Top Shop, and I can still recall occasions when I wore them. There was the dark red velvet maxi-dress with the white lace bodice and the pearl buttons on the sleeves. I wore it to formal dinners and twenty-first birthdays, to sit on the hard benches in the gods at Covent Garden, and to rock concerts at the Roundhouse. Then there was the purple hooded maxi-coat with the cream lining whose first outing was to the theatre on my nineteenth birthday, and which enveloped me on a memorable, misty, romantic January night while being “walked home” from a dance at UCH to my student residence. Alas, the coat was later to succumb to an unfortunate encounter with the wheels of a luggage trolley on Euston station.

As a result of these sublime purchases, I ended my first term term with my first overdraft. The solution was obvious, and I spent the Christmas vacation working at Oxford Circus. The hours were long, that early closing day abandoned during this busy time, and evening opening extended. The crowds were intense, the bright shop lights were hot, and I left every evening feeling as though my eyes had been boiled…and I loved every minute of it. The other girls were fun, the supervisors a source of amusement, and the holiday shoppers good tempered.

I was “on jewellery,” and it was the year of the stars and the moons. I guarantee that any girl who walked down Oxford Street that December will remember them: ordinary hair clips with a little diamante star or moon attached to the end. It required but little skill to conceal the clip so that the stars and moons shone out like diamond confetti. Every morning before we arrived sack loads of these desirable items had been delivered. By midmorning we would have sold out, and desperate customers, undaunted by any thoughts of hygiene, were more than eager to remove those with which we had adorned our own hair. When this last source was exhausted, we assuaged their disappointment with the assurance that there would be more deliveries soon, and so there were, supplies arriving at frequent intervals throughout the day. How many thousands of stars and moons must have graced London’s Christmas and New Year parties.

The other must-have artefact that year was a mirror set in a pink plastic sphere, supported on a purple plastic base; Top Shop had widened the meaning of accessories. While girls bought their own stars and moons, boyfriends had clearly understood that the most felicitous Christmas present they could proffer would be a pink and purple mirror. Our jewellery counter stood just inside the store’s main entrance, and anxious young men, coming to a halt in front of us, would try to convey by word and gesture what they sought. Their relief was palpable when, understanding their requests, we pointed them towards the basement. Having no Significant Other that Christmas, I bought my own mirror – at staff discount. It was never a very practical object, its use limited to the tortuous application of mascara and lipstick, but it provided a cheery presence sitting on my desk or a convenient shelf through a succession of student halls and shared flats.

What I did not realise at the time was that my beloved department stores, facing increasing rents and rates, changing consumer tastes, increased labour costs, and competition from chain stores, were already in decline. Most of them would disappear in the coming decades. Marshall and Snellgrove merged with Debenhams when they both faced financial difficulties, rebranding as Debenhams in 1974. Nonetheless it went into liquidation and closed its doors in February 2021, finally broken by the growth of online sales and the impact of Covid. Bourne and Hollingsworth had already closed in 1983. DH Evans, purchased by Harrods in 1954, was rebranded as House of Fraser in 2001 but closed in 2022.

And Peter Robinson? In 1974 the Burton group split Peter Robinson from Top Shop, and the Oxford Street store became known as Top Shop and Peter Robinson. By the end of the seventies the Peter Robinson name had disappeared entirely, with the shop rebranded as Top Shop and Top Man, the latter a branch of Burton’s tailoring. In the 1990s Topshop became all one word, expanded to fill the entire store, and branches peddling fast fashion proliferated in the provinces and abroad. For a time, it was hugely popular, but I had long since ceased to find its clothes exciting or attractive. On the contrary by then I was aware of a certain malaise permeating the formerly vibrant British high streets, hiding behind the facades of cheap and garish outlets trading in dubiously sourced garments. Arcadia bought up the Burton group in 1997, but by 2010 they too had begun shutting stores as online shopping increased, in 2020 they went into administration, and the last of the Topshops, including the Oxford Circus branch, closed their doors.

Nike and Vans occupied the empty building. O Peter Robinson, your beautiful store was filled with trainers. But worse is to come, for now the trainers too have moved on, and, the ultimate indignity, the Swedish flat pack furniture giant, Ikea, is scheduled to move in later this year.

I had not visited Oxford Street for many years, but on a recent trip to town, with an hour to spare, I walked from Tottenham Court Road to Marble Arch. It was not a cheerful peregrination. Only two of the glorious department stores remain: Selfridges and John Lewis maintain a dignified if somewhat subdued presence at Marble Arch. The rest of the street hosts dreary chain stores and vacant, shuttered store fronts, punctuated by an extraordinary number of souvenir shops offering tourist tat – union jack tea towels, policemen’s helmets, fridge magnets of king Charles, plastic models of tower bridge, – and gaudy American style candy stores. Both the latter are allegedly fronts for the sale of illegal goods and money laundering, and police raids regularly seize counterfeit and unsafe items. And at Oxford Circus I contemplated a sorry shell, once Peter Robinson’s glorious shopping mecca. Boarded up, grubby and unloved, even the beautiful lamps which once graced its exterior shrouded in plastic, it was a pitiful spectacle.

Boarded up, grubby and unloved, even Nike have now moved on.

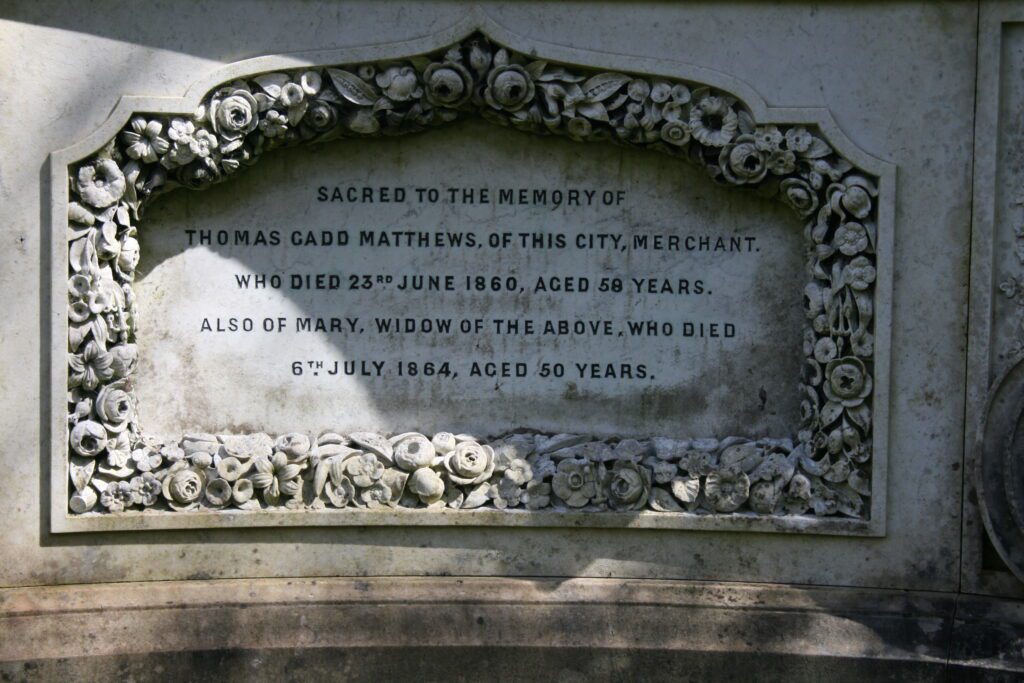

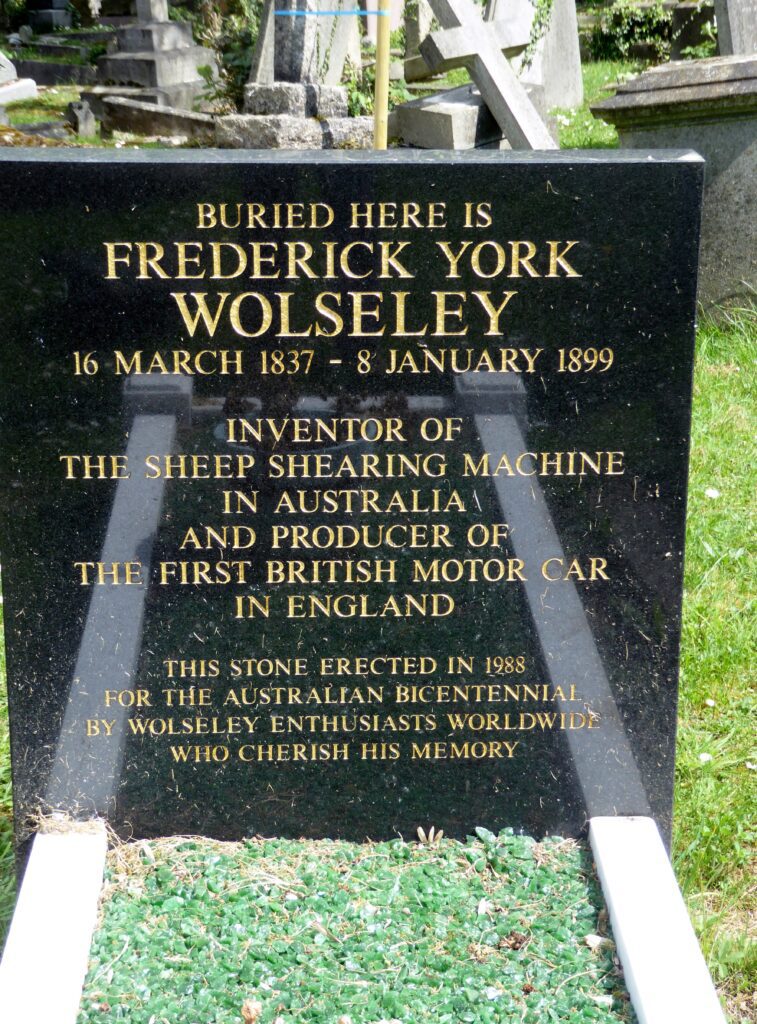

I made my way to Highgate Cemetery wondering how Peter Robinson would feel about the demise of the magical world of department stores. When he died, he left over a million pounds in his will, around £113.5 million in today’s money, so it was no surprise to find him, with his wife and youngest son, Walter, in a large family tomb in one of the most expensive locations in Highgate West, between the Circle of Lebanon and the terrace catacombs. Yet it was not a welcoming nor an attractive grave, built of a cold granite and stone, lying close to the cemetery wall, and overshadowed by a gloomy evergreen.

But Peter Robinson died a phenomenally successful Victorian businessman, the grave was probably to his taste, and there is no reason to imagine that the store I knew in the 1970s would have been any more congenial to him than the prospect of another Ikea blighting the land is to me. I suspect he would have been appalled by Top Shop, the stars and moons, the pink and purple plastic mirrors invading his elegant shop. Maybe he is best left with his memory of it as it was in his day, as I am with my memory of it fifty years ago and almost a hundred years after his death: holding fast to its old fashioned, restrained glamour while simultaneously incubating an exotic and beguiling parvenu in its basement.

In Loving Remembrance

of

Peter Robinson

of Womersley House, Crouch Hill,

and of

Oxford Street and Regent Street, London.