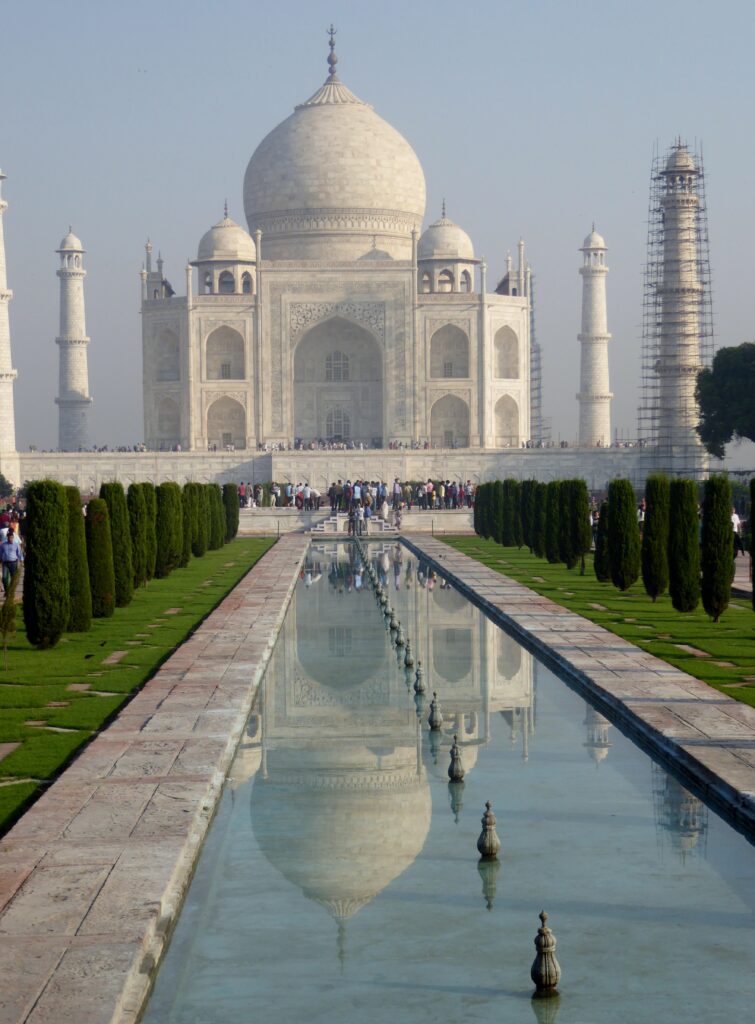

It is always galling to be obliged to agree with any timeworn banality; galling but sometimes unavoidable, for it is impossible to deny that the Taj Mahal is the most beautiful mausoleum in the world, surpassing all others, defying hyperbole and meretricious adjectives.

Commissioned by the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan when his wife Mumtaz Mahal died giving birth to their fourteenth child in 1631, the Taj has accreted myths, usually with little substance. It is said to be a monument to a great love story, that Shah Jahan was inconsolable after the death of his wife, that he planned to build a Black Taj for himself on the other side of the Yamuna River linking the two mausoleums by a bridge. There are stories of him severing the heads and gouging the eyes of his architects and craftsmen once the building was complete to prevent the creation of a rival structure. Later when deposed by his son, Aurangzeb, and imprisoned in the Agra Fort, it is claimed that Shah Jahan spent his last years gazing intently at the Taj, and when his sight began to fail, he lay in bed contemplating its reflection in a diamond fixed to the wall.

Yet such is the mystique and allure of the Taj Mahal that it has no need of fabricated legends. It stands at the apotheosis of Mughal architecture, drawing on Timurid building styles inspirationally fused with the traditions of the Indian subcontinent. Its roots lie in the mausoleum of Timur (Tamerlane) in Samarkand. Gur-e- Amir, the Tomb of the King, was built in 1403 when Timur’s grandson and chosen heir died. It became the family crypt of the Timurid dynasty, later housing Timur himself, his sons, and other grandsons.

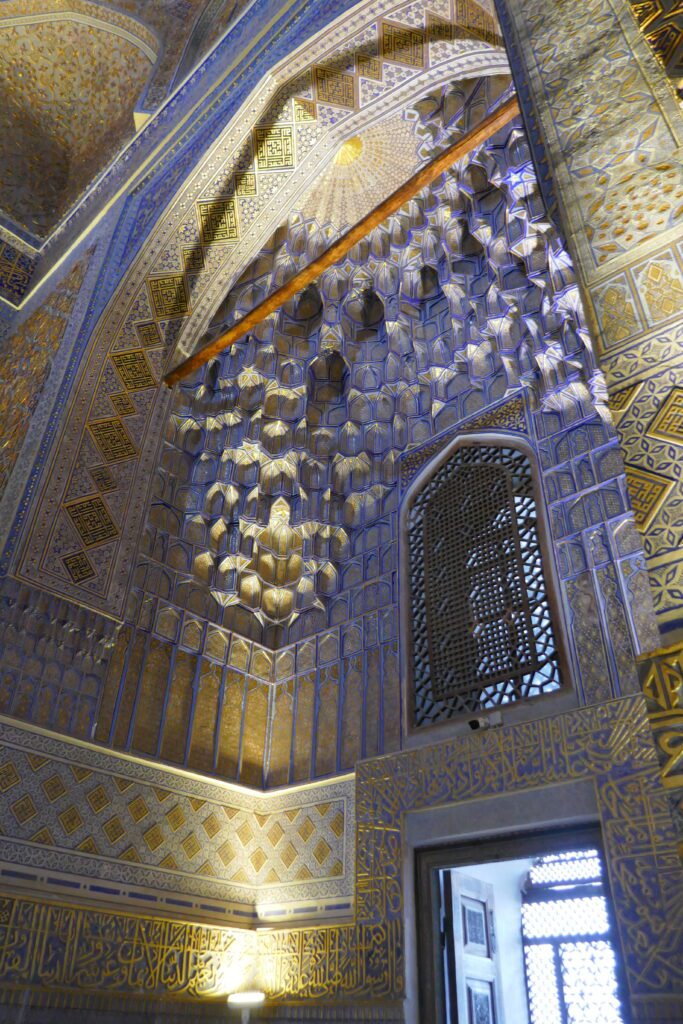

At the Gur-e- Amir complex a traditional Islamic iwan or gateway opens to a courtyard and a symmetrical mausoleum with a fluted azure dome. The gateway comprises a rectangular space walled on three sides and decorated with calligraphy and blue ceramic tiles bearing geometric designs. Within the eight-sided mausoleum blue tiles jostle with onyx and marble stalactites. A dark green jade cenotaph indicates the location of Timur’s tomb which lies in the crypt beneath.

The Gur-e-Amir has attracted its own improbable folktales, for inscriptions on Timur’s cenotaph read:

When I rise from the dead, the world shall tremble

Whosoever disturbs my tomb will unleash an invader more terrible than I.

The Russian anthropologist Gerasimov opened the tomb in 1941… two days later the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union. Stalin allegedly believed the curse and had Timur’s body reburied with full Islamic burial rites…to be rewarded with the Soviet victory at Stalingrad.

Timur was the progenitor of the Mughal dynasty, for Babur, the first Mughal Emperor (1483-1530) was descended from him on his father’s side. Babur inherited Fergana in eastern Uzbekistan and conquered Kabul and Samarkand, before moving on to India, taking Delhi and Agra. And it was the tomb built for Babur’s son, Humayun, which was the first great Mughal architectural masterpiece.

Humayun’s tomb in New Delhi, commissioned by his Persian wife and designed by Persian architects in 1562, introduced central Asian architecture to India. It was modelled on the Gur-e- Amir with the same traditional gateway, geometrical symmetry, central bulbous dome, arched alcoves, lattice stone screens, and a paradise garden. The enclosed garden, divided into quarters with a main axis of water, was the first garden tomb on the Indian subcontinent. But the mausoleum also drew on Indian devices with decorative chattri, and it was built using indigenous stone, with red sandstone facework, inlaid with bands of white marble. The builders embraced the hierarchical use of sandstone and marble representing the kshatriyas (warrior caste) and Brahmins (priest caste) respectively.

At Sikandra, the mausoleum of Akbar, (1605) the third Mughal ruler, exhibits the same synthesis of styles, combining a traditional Islamic gateway, Arabic calligraphy and lattice work, with the use red sandstone bearing white marble features, and with chattri topped minarets at each corner of the gateway.

The tomb of Mizra Ghiyas Beg, the Itmad-ud-Daulah, or Baby Taj, marks the transition between the first monumental phase of Mughal architecture, exemplified in the red sandstone and marble decoration of the Humayun and Akbar tombs, and the second phase of white marble buildings inlaid with delicate pietra dura detailing. Built by Nur Jehan, wife of Jehangir, the fourth Mughal Emperor, for her father in 1622, the Baby Taj is the first Mughal structure built completely of marble. It stands on a red sandstone plinth, its walls inlaid with polychromatic precious and semi-precious stones and perforated by jali screens with ornamental patterns. Octagonal minarets, topped by chattri, rise at each corner, maintaining perfect symmetry. Often described as a jewel box, it is acknowledged as the ultimate prototype and inspiration for the Taj.

With the Taj Mahal, Indo-Islamic architecture reached its apogee. The Taj retains its Persian roots: the traditional gateway; the symmetry, balance and harmony of the mausoleum, with a white marble minaret at each corner, extending to the identical sandstone mosque and guest house which flank the central structure; the bulbous dome; and lattice windows. Behind a screen the false sarcophagi of Mumtaz and Shah Jahan, who was buried beside his wife three decades later, indicate the position of the burials in the tomb chamber below. In the only asymmetrical element, Shah Jahan’s cenotaph is larger than that of his wife, mounted on a taller base, and with a traditional pen box on top. But the translucent Indian white marble is now the dominant material, used for both the platform and the mausoleum. Both are inlaid with precious and semi-precious stones: jade, crystal, turquoise, lapis lazuli, sapphire, carnelian, coral, onyx. The skill and artistry of the Indian stonecutters, inlayers, and carvers have created exquisite flowers and patterns. Yet withal the complex is set around a Persian garden of paradise completing the perfect synthesis.