It is a truth universally acknowledged that Britain has not been invaded since 1066, when, as alleged by Sellar and Yeatman, “The Norman Conquest was a Good Thing, as from this time onwards England stopped being conquered and thus was able to become top nation.”

Acknowledged, but not entirely true, for though their achievements were usually puny by contrast with the Normans, and though they are not so well remembered, other assailants have landed from time to time, seeking to vanquish and subjugate the land.

Under Sweyn II the Danes took first York in 1069, and then Ely in 1070, before accepting a bribe to leave the country.

The future Louis VIII of France had himself proclaimed king, though never crowned, in London in 1216. He captured Winchester and controlled half of England before being defeated at Lincoln and accepting 10,000 marks to withdraw.

In 1588, when the apparently much greater threat of the Spanish Armada was defeated by a combination of English fireships and British weather, some unfortunate Spaniards landed by default, shipwrecked on the west coasts of Scotland and Ireland. Later, at the Battle of Cornwall in 1595 a Spanish force of four hundred men sacked Mousehole, Penzance, Newlyn, and Paul.

When the Dutch sailed up the Medway to Chatham in 1667, they burned more than a dozen warships and captured the flagship of the English fleet, HMS Royal Charles. Samuel Pepys recorded his alarm:

and so home, where all our hearts do now ake; for the newes is true, that the Dutch have broke the chaine and burned our ships, and particularly The Royal Charles, other particulars I know not, but most sad to be sure. And, the truth is, I do fear so much that the whole kingdom is undone, … So having with much ado finished my business at the office, I home to consider with my father and wife of things, and then to supper and to bed with a heavy heart.

Twenty-one years later another Dutch invasion, led by William of Orange, landed in Devon, with a fleet of 463 ships and 40,000 men. This time they had been invited by the opponents of James II, and when the latter fled the country, he was deemed to have abdicated. William and Mary replaced him, a substitution legitimised by Parliament and hailed as The Glorious Revolution.

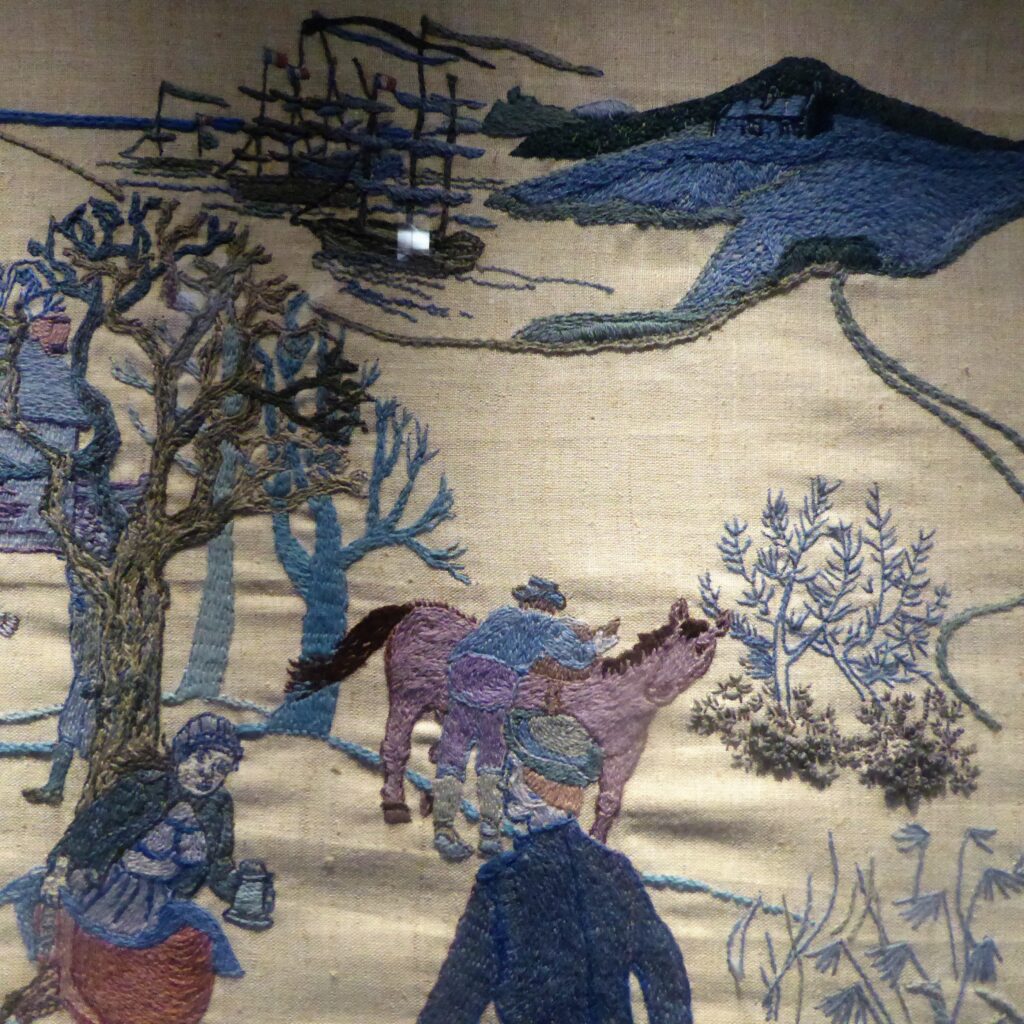

But while that may have been the last successful incursion into mainland Britain, it was not the final landing by a hostile force. On 24 February 1797 around 1,200 French soldiers landed at Carreg Wastad Point near Fishguard in South Wales. This battalion incorporated a penal unit consisting of convicts mobilised for military service. Called the Legion Noire, because they used captured British uniforms died black or blue, they landed appropriately under cover of darkness.

The defending forces were ill-prepared and outnumbered: a quickly assembled group of five hundred reservist militia, aided by the civilian population. Yet the Battle of Fishguard, little more a few skirmishes, was over in two days with the French troops making an unconditional surrender.

Once they had landed discipline had broken down amongst the French troops as they ransacked local farms, looted, and grew intoxicated. Was this why they were so easily defeated? No, it was all down to Jemima.

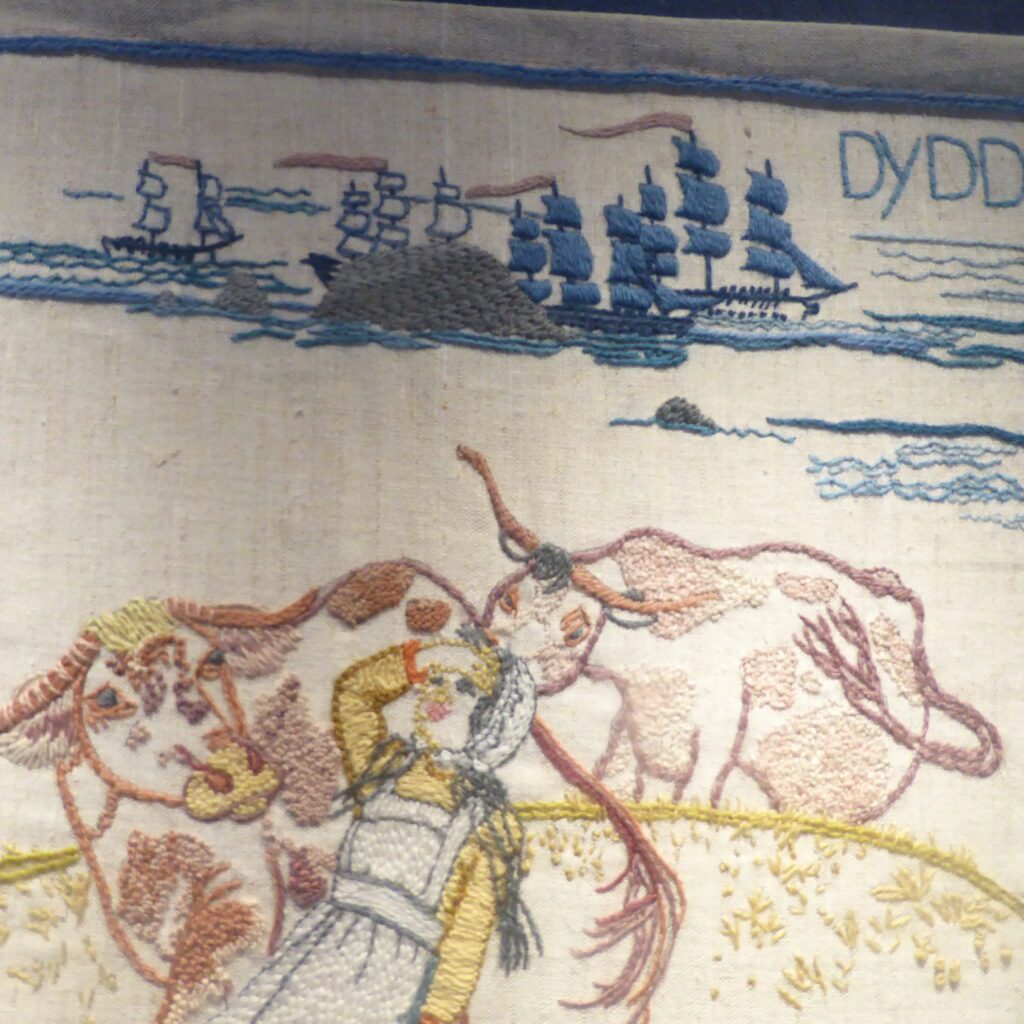

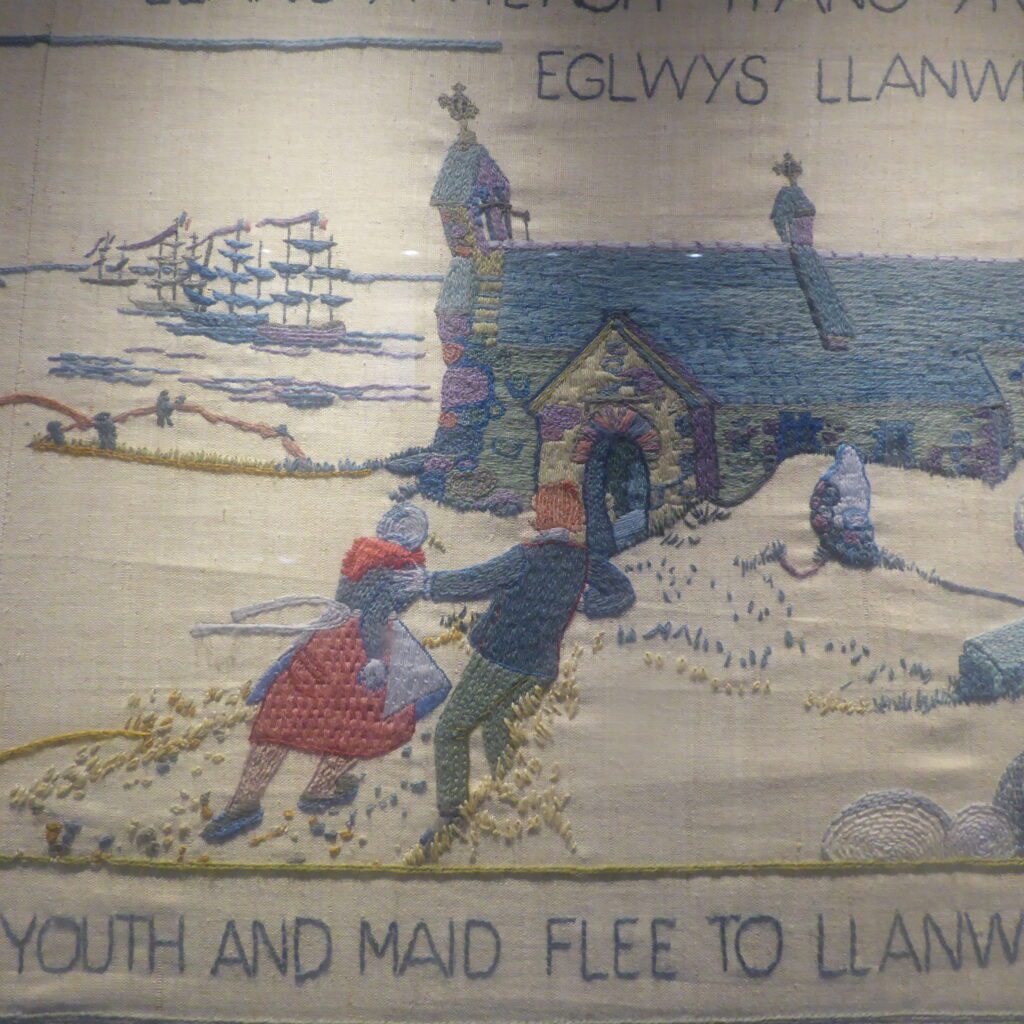

Jemima Nicholas was a cobbler in Fishguard who led a group of women, armed only with pitchforks, against the French. One story describes Jemima single-handedly rounding up twelve French soldiers and holding them captive overnight in a church at Strumble Head. Another has the Welsh women in their traditional red cloaks and steep crowned black hats marching up and down the cliffs until nightfall, and the inebriated soldiers mistaking them for British Redcoats and thinking themselves outnumbered. Instantly demoralised, they capitulated.

Whatever the finer details, the government concurred that Jemima had taken a brave stand against the French. She was awarded an annual pension of five pounds for helping to defeat the invasion.

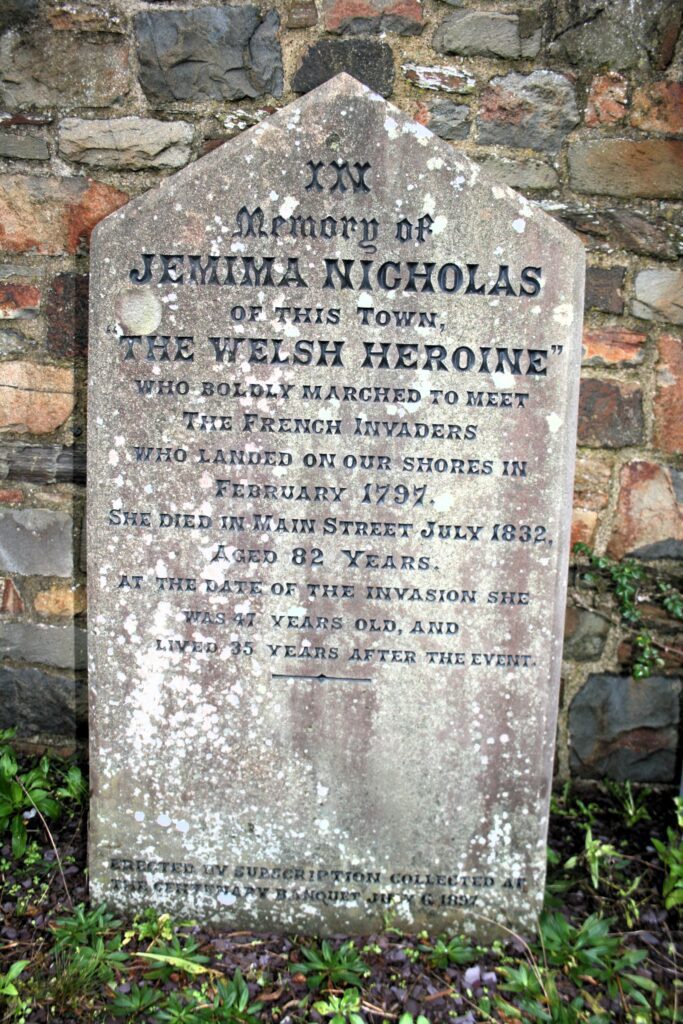

Subsequently known as Jemima Fawr, Jemima the Great, Fishguard’s heroine was buried in the churchyard of St. Mary. There was no headstone at the time, but in 1897 a stone was erected by public subscription collected at a centenary banquet. It records rather quaintly that,

She died in the main street July 1832,

Aged 82 years.

At the date of the invasion she

Was 47 years old, and

Lived 35 years after the event.

A sign above the Royal Oak pub in Fishguard records that the peace treaty was signed there, following the last invasion of Britain.

In 1997, at the bicentenary, seventy-seven local people embroidered the Last Invasion Tapestry employing the same techniques as those used for the Bayeaux Tapestry.

The French are defeated. Hurrah for Jemima!

You can find the tapestry of the Last Invasion in the Fishguard library. And if you want to contrast it with the Bayeaux Tapestry of the Norman Invasion, there is no need to go to Bayeaux. Reading Museum has a perfect copy of the latter and no jostling crowds.

- Sellar and Yeatman, 1066 and All That

- The Diary of Samuel Pepys, 12th June 1667