Wool was the backbone of the economy in Medieval England. From the fourteenth century, the Lord Chancellor, while in council in the House of Lords, sat on The Woolsack, a symbol of England’s wealth. Supposedly, this was a wool bale, although when the seat came to be restuffed, six hundred years later in 1938, it was revealed to be filled with horsehair. The replacement was duly made with wool.

The wool trade peaked in southern England between 1500-1714, providing a generous revenue for the government, which reciprocated briefly by passing a law in the 1570s supporting the industry by enforcing the wearing of woollen caps to church on Sundays.

The wool towns prospered, and with them rose magnificent parish churches, clothiers’ and merchants’ houses. Somerset’s wool towns were not the richest, that distinction went to Suffolk, but there was no doubting their affluence.

Shepton Mallet’s very name echoes its original source of wealth: scoep and tun, sheep and farm. In the eighteenth century there were some fifty mills, spinning, weaving and dying wool, in and around Shepton.

But by the end of that century the southern wool towns were in decline, losing out to the steam powered production of cloth in the north. Surrounded by steep hills and waterpower Leeds became the major wool town.

The population of Shepton Mallet plummeted as unemployment and poverty engendered emigration. By 1801 there were only 5,000 people in the town, and the population remained at that level until the 1950s.

There were partial revivals of the town’s fortunes. For a while it developed a trade in silk and crepe: the silk for Queen Victoria’s wedding dress was produced there. But cheaper imports and changing tastes in fabrics meant that the respite was brief.

In the mid-nineteenth century two railways arrived, a branch of the East Somerset Railway in 1859, and one of the Somerset and Dorset in 1874. Shepton became a centre for storing Farmhouse Cheddar Cheeses while they matured, and then distributing them. “The Strawberry Line” carried strawberries from Cheddar to London and Birmingham. But the Beeching cuts of the 1960s closed these lines and ended the trade.

In 1864 the Anglo-Bavarian Brewery in Shepton was the first to brew lager in England, but it closed again in 1921.

James Allen grew up against this background of a precarious economy. He was born in 1830 at Windsor Hill Farm, just outside Shepton Mallet, where his family operated a corn mill. Such was the poverty in Shepton, that in the Bread Riots of 1842 desperate, starving men, unable to pay for both rent and food, threatened to burn down the mill. James’ older brother persuaded them to leave, promising flour to those who came from Shepton Mallet the following morning, and the mill was spared.

Later the family moved to Highfield House in the town and into the business of storing and distributing cheese.

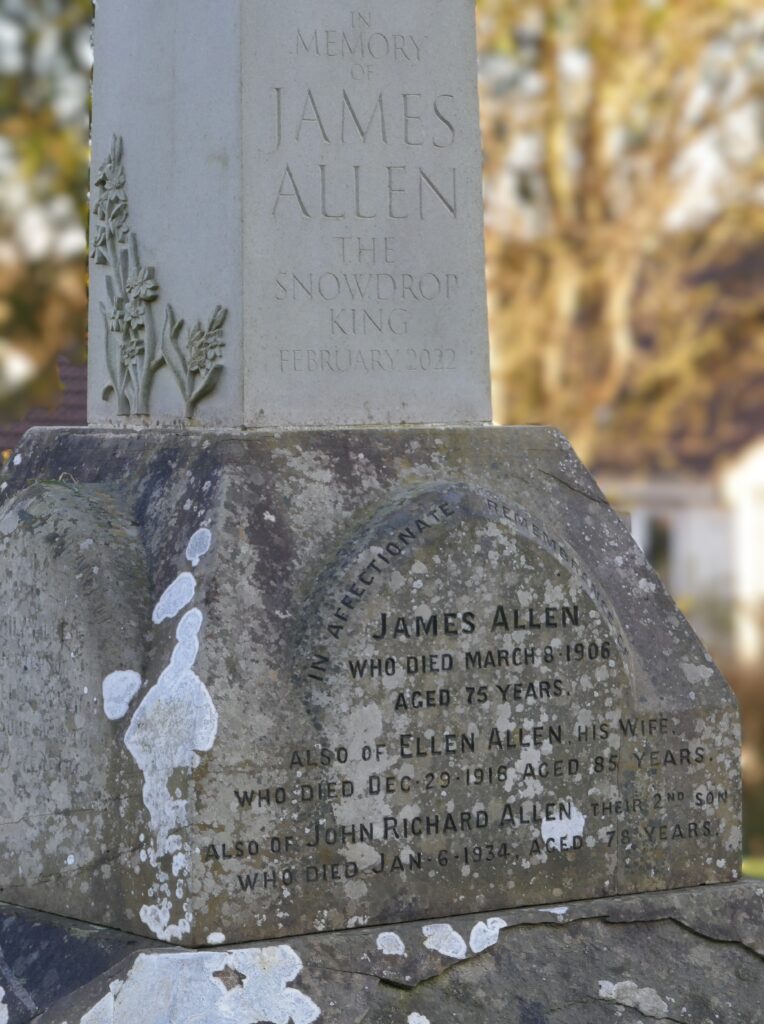

Though Shepton was poor, the Allen family prospered, and their affluence enabled James to pursue his interest in horticulture. He was entirely self-taught but, a passionate galanthophile, he became the first person to breed new varieties of snowdrops from the wild. During his lifetime around five hundred cultivars were produced; he was personally responsible for over a hundred of them. He grew all the species known at the time, crossing and raising hybrids from seed, achieving fame as The Snowdrop King.

After his marriage to Ellen Burt the couple moved across the road from Highfield House to Park House. There he continued his experiments, also breeding narcissi, lilies, a wood anemone, Anemone nemorosa Allenii, and a lavender, Scilla xallenii.

Sadly, the fungal infection Botrytis, followed by an attack of narcissus fly, blighted Allen’s remarkable collection of snowdrops, destroying most of them. But two of his cultivars survive, the exquisite Merlin, with its completely green inner flower segments, and Magnet with its long pedicel causing the flower heads to bob in the breeze.

The Allen family had a prominent role in the town’s affairs, and were generous benefactors, contributing to public works including the town cemetery which opened in 1856. The latter was built with Anglican and Non-Conformists sections and a separate chapel for each; the Allens themselves had converted to Non-Conformism which had a strong following in the town and throughout the West Country.

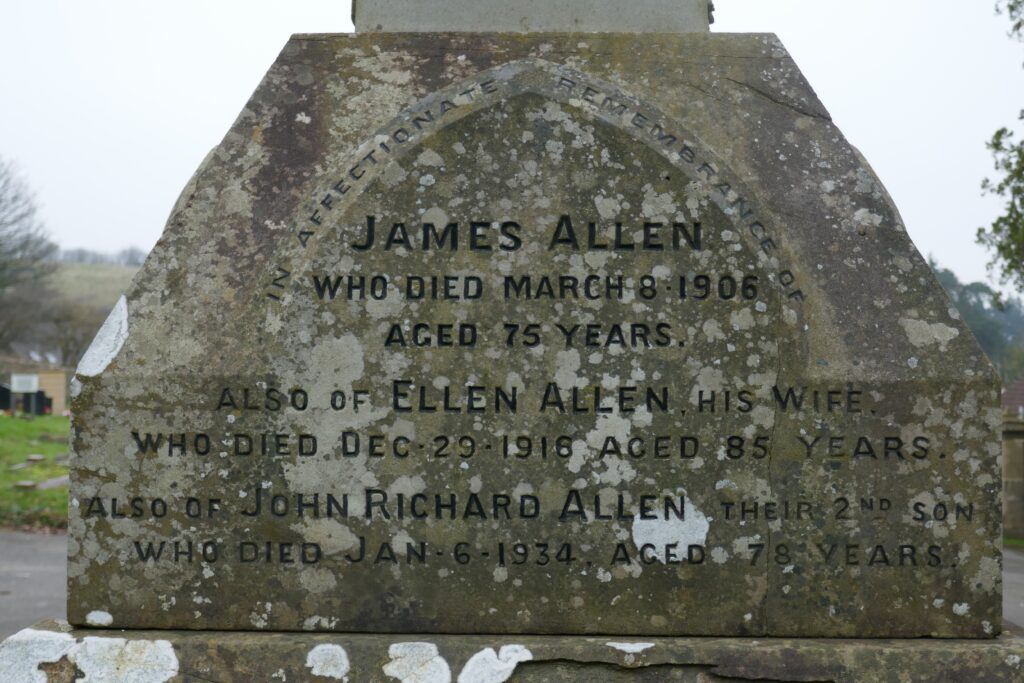

Their wealth and philanthropy, combined with James Allen’s considerable fame in Victorian England, ensured him a prime spot in the cemetery when he died in 1906. He was buried in front of the nonconformist chapel, with an obelisk above him, and surrounded by a circular bed of spring flowers.

Like many Somerset towns Shepton Mallet has never recovered its early prosperity. Today its high street is rundown, empty units like missing teeth alternate with charity shops, and small business ventures have a rapid turnover. Yet Shepton Mallet is undefeated, and last month I attended its Annual Snowdrop Festival.

The festival was founded ten years ago to celebrate James Allen and to support regeneration of the town by raising its profile and attracting visitors. Volunteers from the town’s horticultural society open their own gardens in the summer, raising money to buy bulbs for the Shepton snowdrops project. Every autumn they plant more bulbs. Since they began, they have planted more than 500,000 bulbs around the town at roadsides, roundabouts, and in public spaces, with special attention to parts of the town where flowers are not so commonly seen.

At the February half term, the festival features plant sales, poetry and photography competitions, painting and craft workshops for children, puppet making and storytelling, gardening talks and heritage walks…and a snowdrop themed fashion show.

I joined a walk, and we set out for Windsor Hill Farm, where James Allen was born. Its gates were open, a brasier lit on the patio, and the current owners had prepared tea and cakes, iced with green and white snowdrops, to welcome us.

We walked along one of the two great railway viaducts, the previously overgrown track now cleared by volunteers for cycle routes and footpaths. This work is ongoing and several of my fellow walkers were involved, all adamant that there can be no greater joy than to rise early on a weekend morning for a communal attack on the brambles.

On through the lower part of the old town with the sudden surprise of the lovely old merchants’ houses and the chapel where James Allen married, and his children were baptised.

At Park House again the gates were opened to us, the owners pointing out the locations where James Allen grew his various cultivars. Stripping back layers of ancient wallpaper when they moved in, they had discovered outlines on the wall probably indicating the presence of an indoor greenhouse, a feature much loved by the Victorians. They are currently scrutinizing Allen’s handwritten notes and correspondence held by the Royal Horticultural Society to see if they can confirm this.

We finished our walk beside James Allen’s grave. The original obelisk fell into disrepair and had to be dismantled on safety grounds, but in 2022 a perfect replica was unveiled during the festival.

You do not have to wait until next February to make the acquaintance of James Allen. You can download the Shepton Mallet Heritage Trails at any time. There, alongside the story of the Snowdrop King, you will discover that no lesser an authority than Pevsner claims that the medieval church boasts the finest oak wagon-roof in England; that Shepton Mallet is home to England’s oldest prison (1627), which housed national records including the Magna Carta during World War II, and the Kray twins when they went AWOL from national service in the fifties.

Shepton, you will learn, is the birthplace of Babycham, in 1953 the first alcoholic drink to be aimed specifically at women, and the first to be advertised on commercial television in Britain.

Then there is the Amulet theatre, built in the 1970s and highly rated by the Brutalism Appreciation Society, an enthusiasm admittedly not shared by everyone. And, my favourite, The Rock Flock Roundabout, where the model sheep may sport party hats, green and white scarves, easter bonnets or santa hats depending on the time of year.