Last week I attended the memorial service of a dear friend and former colleague. A Welshman with a great love of literature, he had shared his passion with his children, and they read extracts from two of his favourite books: Richard Llewellyn’s How Green Was My Valley and Dylan Thomas’ Under Milk Wood.

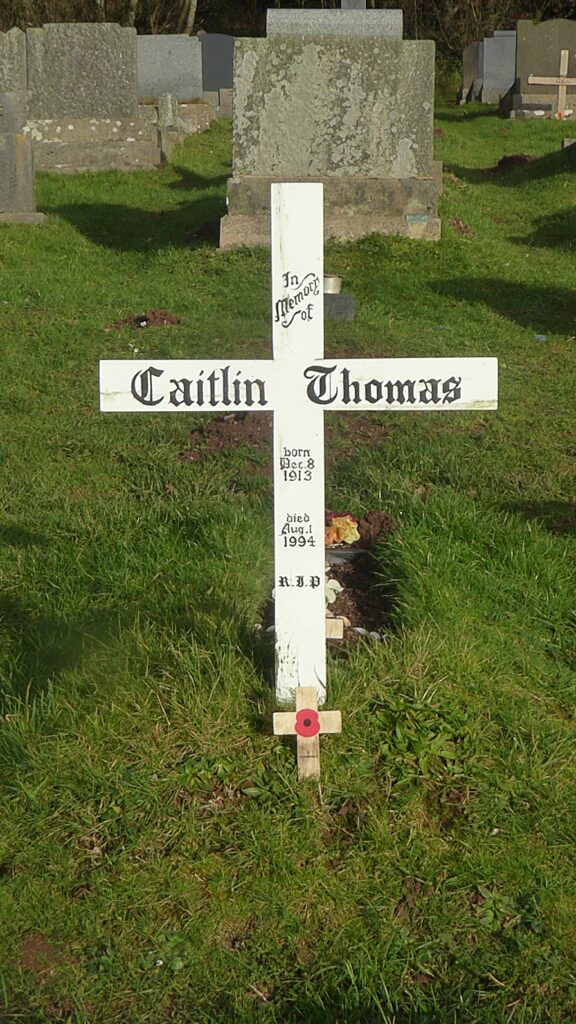

During the summer holidays, some years ago, my friend and I had gone together one day to Laugharne, the small town where the river Taf flows into Carmarthen Bay, and where Dylan Thomas lived from 1949 until his death in 1953. It is believed to be the inspiration for Llaregub, the village in Under Milk Wood. We visited the Boathouse, with its views out over the estuary, where Dylan and his wife Caitlin had lived; the old garage near the house which he had turned into a writing shed; Browns Hotel, where he spent so much time drinking that he used the bar’s telephone number as his own; and the graveyard of St. Martin’s church where he is buried. And there my friend spoke from memory his favourite lines from the “play for voices,” Reverend Eli Jenkins’ morning verses:

Dear Gwalia! I know there are

Towns lovelier than ours,

And fairer hills and loftier far,

And groves more full of flowers,

And boskier woods more blithe with spring

And bright with birds’ adorning,

And sweeter bards than I to sing

Their praise this beauteous morning…

…A tiny dingle is Milk Wood

By Golden Grove ‘neath Grongar,

But let me choose and oh! I should

Love all my life and longer

To stroll among our trees and stray

In Goosegog Lane, on Donkey Down,

And hear the Dewi sing all day,

And never, never leave the town.

And his sunset poem:

… every evening at sun-down

I ask a blessing on the town,

For whether we last the night or no

I’m sure is always touch and go.

We are not wholly bad or good

Who live our lives under Milk Wood,

And Thou, I know, wilt be the first

To see our best side, not our worst.

O let us see another day!

Bless us all this night, I pray,

And to the sun we all will bow

And say, good-bye – but just for now!

The radio play was Dylan Thomas’ last work, completed only months before his death in New York in 1953. Recounting twenty-four hours in the life of the town and its inhabitants, it reads like a fairy tale, at one moment all bawdy, exuberant Chaucerian humour, the next tender, melancholy and lyrical. The torrent of language and imagery, the alliteration and assonance, is unequalled. And the grace and humanity of the acknowledgement that “we are not wholly bad or good” is a sentiment which I know appealed to my friend whose inclination was always to see the best side of anyone.

The transience of life, death, and mortality, were recurring themes in the poetry of Dylan Thomas, and while Eli Jenkins prayed for another day, an earlier poem, And Death Shall Have No Dominion, published in 1933, described death as part of Life’s Cycle:

And death shall have no dominion,

Dead men naked they shall be one

With the man in the wind and the west moon;

When their bones are picked clean and the clean bones gone,

They shall have stars at elbow and foot;

Though they go mad they shall be sane,

Though they sink through the sea they shall rise again;

Though loves be lost love shall not;

And death shall have no dominion.

Physical bodies may perish but they become one with the cosmos, moving into a future beyond death as part of a life force, embedded in plants or the sun, at one with the wind and the moon, with nature, the stars and the sea, so that death is a union rather than a division, in fact life only gets meaning from death, with death a guarantee of immortality.

In his 1946 collection of poems, Deaths and Entrances, Thomas returned to the same theme with his Poem in October, recounting the walk he took on his thirtieth birthday: “It was my thirtieth year to heaven.” As he describes his physical walk along the shore and up the hill, the seasons shift, and he recalls his childhood and youth. Ageing then is not a matter of getting older and mourning for a lost youth, not a one-way journey to death, but a chance to revisit the past and be enriched by it, rediscovering a child’s sense of wonder and an intimate connection with all of nature and life. Life is impermanent but humanity and nature are woven together, and individuals ultimately become part of the natural order.

But it is another of Thomas’ poems, the villanelle, Do Not Go Gentle into that Good Night, containing a rather different message, which is frequently read at funerals and memorials.

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rage at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Published in 1951, the poem is commonly interpreted as a call to defy death and not to waste any opportunities, live life as best you can before it is too late. Moreover, although death is inevitable, life is precious and worth fighting for, death should not be accepted passively or in a spirit of resignation, rather we should resent and abjure death, resist our fate, and fight to live. But if the poem were merely flailing against the inevitable it would be an odd choice for funerals when it is too late for resistance or indeed for correcting life’s errors and omissions. The burning anger, the rage, is surely that of those who are left behind when those they love die. In the last stanza Thomas drops the discussion of mortality in general and the poem moves to his father’s imminent death, and a more personal expression of grief. Here is the personal despair, the desperate visceral plea, – don’t go, don’t leave me:

And you my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night

Rage, rage, against the dying of the light.

Different poems speak to different people: though I admire the writing, I am uncomfortable with the sentiments of And Death Shall Have No Dominion and Poem in October, for they sound like sophistry to me, desperate attempts to deny death without recourse to conventional religion, but no more credible than the latter. I prefer the frank and simple honesty of Eli Jenkins, who for all his belief, longs and begs for one more day. And it is with the hopeless rage at the dying of those we have loved that I empathise most strongly; it may be a little odd to ask people, when they are old or ill, tired and wanting to rest, to keep up the fight, a little selfish, but understandable.

Dylan Thomas himself was only thirty-nine and on his fourth reading tour in the United States when he died from a cocktail of bronchitis, pneumonia, emphysema, and asthma exacerbated by heavy drinking- though his widely quoted claim to have “just drunk eighteen straight whiskies” was questionable. His body was shipped home to Wales to be buried in the churchyard at Laugharne.

Afterthought

If too much reflecting on death has engendered a little despondency, let me cheer you up with the response of Kenneth Tynan, not a man who was easily impressed, to early critics of Under Milk Wood. He delineates the charges made against the play: “that it approaches sex like a dazzled and peeping schoolboy. And that Llaregub, so far from being a real village, is a “literary” village that Thomas had adorned with a false moustache of lechery – “Cranford” in fact, with the lid off… To all these accusations Thomas must plead guilty. Yet we, the jury, rightly acquit him. He talks himself innocent: on two dozen occasions he gets past the toughest guard and occupies the heart.” Tynan went on to praise the “manic riot of his prose,” and, in quite a manic riot himself, continued, “He conscripts metaphors, rapes the dictionary, and builds a verbal bawdy-house where words mate and couple on the wing, like swifts. Nouns dress up, quite unselfconsciously, as verbs, sometimes balancing three-tiered epithets on their heads and often alliterating to boot.”

Kenneth Tynan on Under Milk Wood: a true comedy of errors, reprinted in The Observer 28 February 2014, originally published 26 August 1956.