The Victoria and Albert has always been my favourite museum, and Tipu’s Tiger one of my favourite exhibits. Made from Indian jack wood carved and painted, the Tiger straddles a near life-size, red coated British officer. French engineers at Tipu’s court constructed the tiger’s mechanism which is operated by a crank handle causing the soldier’s arm to lift as he wails and squeals in response to the tiger’s mauling, while the latter grunts.

Tipu Sultan (Sultan Fateh Ali Sahab Tipu, 1751-1799), also known as the Tiger of Mysore (Sher-e-Mysuru), became the Muslim ruler of the Kingdom of Mysuru in South India following the death of his father, Hyder Ali, in 1782. He fought against the British East India Company in the four Anglo-Mysuru Wars, seeking to check the Company’s advance into southern India.

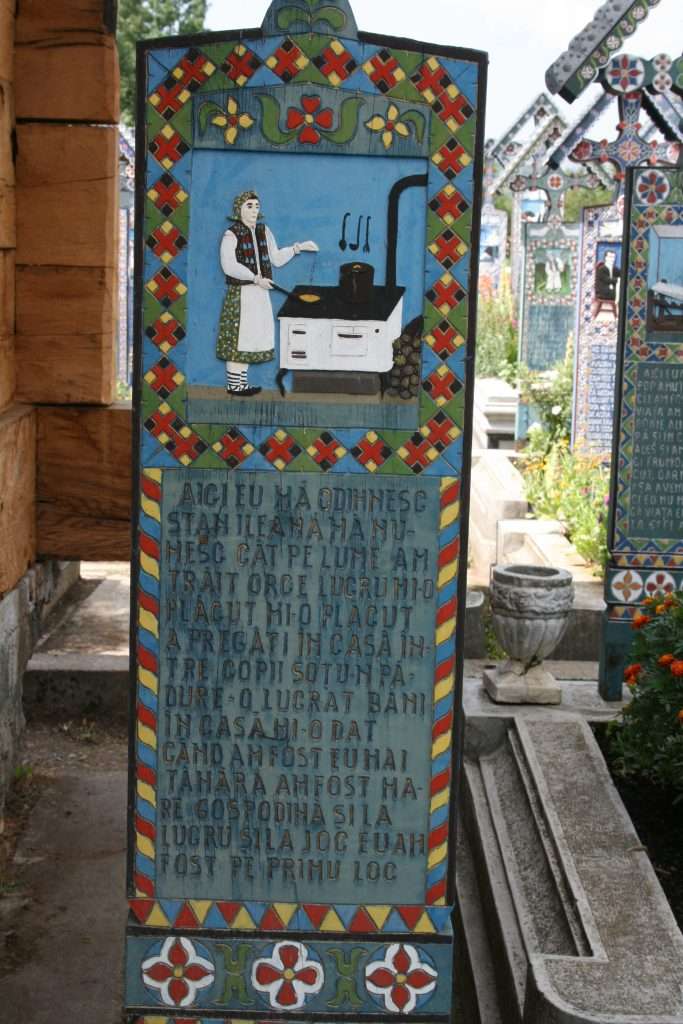

The tiger was Tipu’s state symbol: an apocryphal story has him face to face with one who pounced while he was out hunting; when his gun failed Tipu killed the tiger with his dagger. What is certain is that tiger motifs and stripes decorated the walls of his palaces and the uniforms of his soldiers. In the summer palace, Daria Daulet Bagh, at Srirangapatna, his golden throne set with rubies and diamonds stood on a life size wooden tiger and was embellished with tiger head finials. The hilts of his swords, his rings, his cannon, the pole ends of his palanquins all flaunted tigers. And in his music room sat the magnificent automaton.

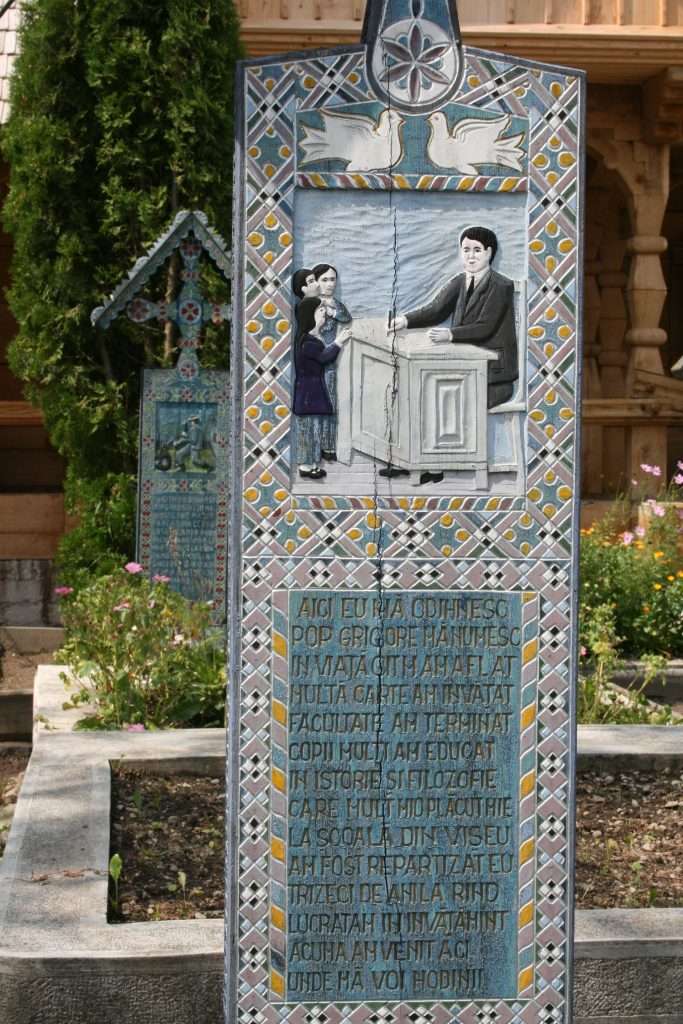

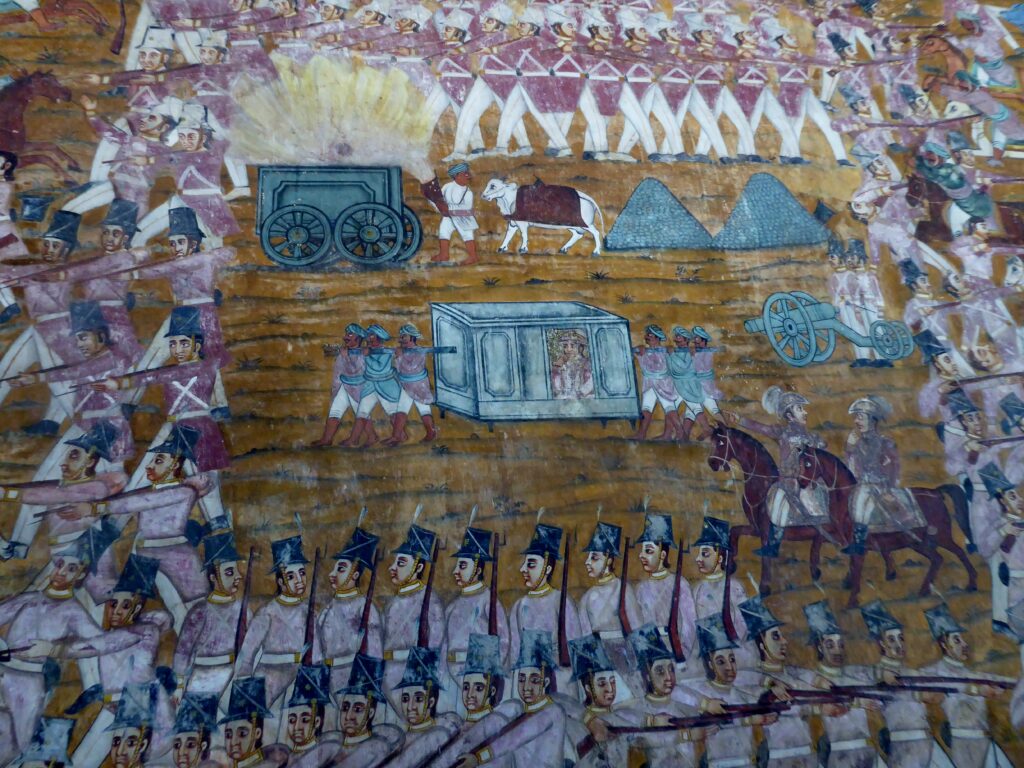

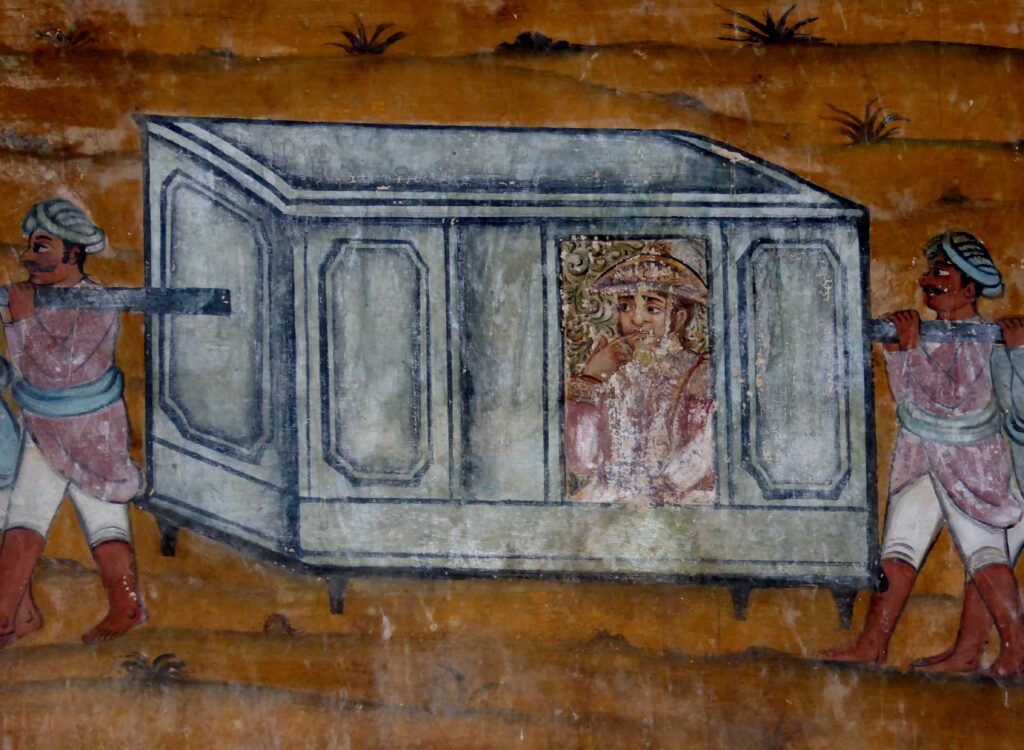

Tipu had built his summer palace after the Second Anglo-Mysuru War. Lavish decoration covers the interior with floral designs on the ceiling and murals of his campaigns on the walls. The depiction of the victory of Hyder Ali and Tipu over the English under Colonel Bailee at the battle of Pollilur in 1780 shows a nervous looking Bailee cowering in his palanquin despite being surrounded by his redcoats.

The Third War however ended in defeat for Tipu when the Nizam of Hyderabad, seeing which way the wind was blowing, changed sides and signed a subsidiary alliance with the British East India Company. He is portrayed alongside a cow and a pig; the reference is not designed to be complimentary.

Tipu was forced, by the Treaty of Srirangapatna 1792, to surrender half of his kingdom to British East India Company and its allies, and two of his sons were handed over to Cornwallis as hostages until he paid indemnities. A painting displayed in the palace, today a museum, shows the children with their custodian and Tipu’s Ambassador to France, Mir Ghulam Ali, who accompanied them to Madras (Chennai). Alongside are portraits of Tipu himself, one by an unknown Indian artist and one by Zoffany.

Seven years later Tipu’s defeat and death at the hands of the British when they breached the city walls at the Siege of Srirangapatna, brought the fourth Anglo-Mysuru war to an end. When his advisers urged him to escape via secret passages, Tipu responded: “Better to live one year as a tiger, than a thousand years as a sheep.”(or, in some versions, a jackal)

His death was celebrated with a public holiday in Britain, and the soldiers plundered his palace before the “formal” distribution of loot was organised by the “prize committee,” with the most senior officers receiving the most valuable treasures. The magnificent Tiger Throne was broken up and the parts distributed to the Company’s officers. Some of the most precious items were sent to the British royal family, including three hunting cheetahs. The mechanical tiger was housed in the museum of the East India Company and when the company was dissolved, and the museum closed, its artefacts were divided between the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert. And so the tiger came to South Kensington.

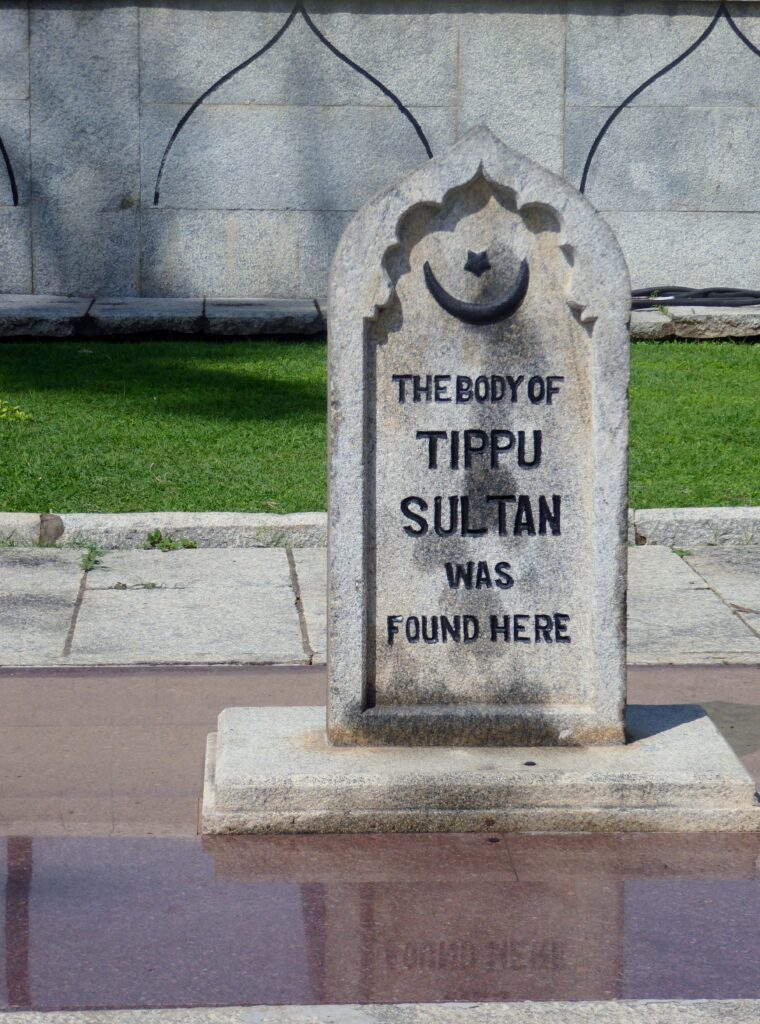

Tipu’s body, recovered from where it lay near the Hoally Gateway of the fort, was buried beside his parents in the Gumbaz (mausoleum) which he had built for them. A majestic structure, built in the Persian style with an elevated platform supported by black granite pillars, it is surrounded by landscaped gardens.

Tipu’s wife and sisters did not quite merit admission to the Gumbaz but are buried in the gardens.