Of course I did not have high expectations of the new government. Labour in name only now, the party has moved, save for brief anomalies under Michael Foot and Jeremy Corbyn, steadily further towards the right since the post war years of the Atlee government. Blair jettisoned the party’s socialist past when he rewrote Clause Four, ending the historic commitment to common ownership of industry, passively accepting the results of Margaret Thatcher’s contemptible sale of shares in privatised utilities. With equal passivity the Starmer government has accepted the results of the 2016 referendum on the EU despite the lies told by the Johnson administration to promote Brexit. There is little sign of any attempt to tackle inequalities of wealth and income, save a half-hearted commitment to end the use of offshore trusts to avoid inheritance tax. Blair lied in Parliament and to the public, claiming that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction, to justify his decision to invade. The current Labour government has been at best equivocal over Gaza: in an early interview Starmer argued that Israel had the right to cut off necessities of power and water in Gaza. 146 countries recognise the existence of Palestine – Britain is not one of them. 137 member states of the United Nations recognise Palestine – Britain is not one of them. Instead, Britain is the only permanent member of the UN Security Council apart from the USA not to support Palestinian membership of the UN. Starmer was even slow to join countries calling for a ceasefire in Gaza and will not suspend arms exports to Israel. Indeed, arms sales around the world continue to be a pivotal part of the British economy as much under Labour as under Conservatives. In relation to asylum seekers Starmer voices the same “stop the boats” rhetoric as his recent Tory predecessors, only choosing to send them to Albania instead of Rwanda for “processing.” It was not anyone’s enthusiasm which brought this government to power but antagonism to fourteen years of Tory rule, a low turnout, the collapse of the SNP in Scotland, and Farage’s Reform Party taking votes from the Conservatives.

But if all this is enough to drive the iron into anyone’s soul, it is sometimes the relatively trivial which leaves us spluttering with incoherent rage. Having pledged to run a government of high standards, and end cash for access scandals, the Prime Minister, his wife, the deputy prime minister and the chancellor have been accepting freebies from the Labour peer Waheed Ali (appointed a life peer by Blair in 1995). It began with “Passes for Glasses” when Waheed was revealed to have unrestricted access to Downing Street after buying the prime minister £2,485 worth of spectacles. Then followed revelations of £107,145 spent by Waheed on Starmer’s wife’s clothes, £40K on tickets for him to watch the Arsenal football team, and £4k for tickets to a Taylor Swift concert…Starmer declares all this to be perfectly legal since he declared the gifts, albeit belatedly, but even his own MPs have found it morally questionable. Nor did it help when he whined that the security issue meant that he would never be able to go to an Arsenal game again unless he accepted corporate hospitality in a private box. But the utterly risible last word (or probably not) came from Foreign Secretary David Lammy suggesting that the freebie clothes were justified because the Starmers sought to look their best when representing the UK on the world stage.

Anyone incensed by this level of hypocrisy and political idiocy, can do no better than to spend a little time in the empathetic company of the furious, irascible William Cobbett (1763-1835). For no one does splenetic fury like Cobbett, he is never rendered speechless with indignation. Cobbett had little interest in politics beyond England, he was no citizen of the world, but he more than made up for his narrowness of focus with the passion he brought to bear on the question of rural poverty. By the time he published his Rural Rides in 1830 he could not write a paragraph without a vitriolic outburst expressing his utter contempt for those responsible, most notably successive Whig and Tory governments, for the proletarianization of agricultural workers.

William Cobbett did not begin life as a radical. Indeed, as a young man he was conservative to the point of being reactionary, and his later views developed in an idiosyncratic, unsystematic way. The son of a farmer and publican, he received little formal education and began work as a ploughboy before, desiring to see the world, he joined the army and found himself between 1784-1791 in New Brunswick, Canada. He used the time to study English and French grammar. Seeing his senior officers appropriate some of the pay of the common soldiers, he began to question authority, and on his return to England published his first pamphlet exposing their peculations and charging the officers with corruption. In The Soldier’s Friend he described the low pay and harsh treatment of the enlisted men. Then, fearing that he was about to be indicted and imprisoned in retribution, he fled to the USA. And during this period the most unattractive side of Cobbett emerges. He became a rabid British loyalist, an anti-Jacobin critical of Jefferson’s support for the French revolutionary government, a supporter of war against the Franco-American alliance. He denounced democracy and reviled his radical compatriot, Tom Paine. Cobbett was unashamedly xenophobic and bigoted, critical of any country which rivalled Britain, outrageously antisemitic, with a deep-seated loathing of Irishmen and of abolitionists like Wilberforce. When his writing came to the attention of the Tory Prime Minister, William Pitt, he was welcomed back to England, and in 1800 Pitt offered to subsidise his writing as an apologist for the Tory government and a polemicist against radicalism. How then did this monster come to be admired by Karl Marx, Michael Foot, EP Thompson?

Well, he changed: while many people move politically to the right as they grow older, Cobbett moved the other way. At first supporting Pitt, he was nonetheless incorruptible, refusing Pitt’s offer, and publishing his own views in his one-man weekly paper, The Political Register*, produced from 1802 until his death in 1834. And those views became very antiestablishment as Cobbett looked around him at the state of England in the early nineteenth century and saw corruption, cruelty, venality, and injustice. The Register, dubbed Cobbett’s Twopenny Trash by his detractors, a designation which he enthusiastically embraced, became increasingly critical of the war with France, the military, the church, big landowners, rotten boroughs – the “Accursed Hill” as he refers to the notorious rotten borough of Old Sarum – and, the spawn of those rotten boroughs, the Parliament and government at Westminster.

For his pains Cobbett found himself in Newgate prison between 1810-12 after being convicted of sedition. Between 1817-19 he fled to the USA again to avoid a further incarceration as radicals like himself were rounded up. This was a very different Cobbett from the man who had vilified Tom Paine, and when he returned to England, he brought Paine’s bones with him. Paine, once a hero in the USA, had become an outcast on account of his negative views on organised religion. He died in poverty, and his grave had been neglected until Cobbett sought to make amends for the injustice, he had done him. Cobbett wanted to build a mausoleum and memorial for Paine with money raised by public subscription, but Paine’s bones met with the same lack of respect in England as in the USA and the appeal failed. Cobbett kept the bones until his death when they were lost.

Meanwhile Cobbett’s radical beliefs coalesced around the plight of agricultural workers and small farmers. Cobbett loved the rural England he had known in his childhood and youth. He yearned for a golden age when every farmer brewed his own beer and fattened his own hog; when farmers lived, worked, and ate alongside their labourers. But Cobbett was no mere nostalgic dreamer, for alongside his journalism he was a practising farmer. His knowledge of agriculture, crops and soil was encyclopaedic. And between 1821-1826, travelling on horseback round the counties of southern England, he built up a portrait of rural life. He studied the farms, the fields, the crops, the animals, he talked to the farmers and the farm labourers. He visited the markets and fairs. Cobbett published his findings in Rural Rides. He had an emotional link to the countryside and his vivid prose is lyrical and romantic, but it hard hitting too. For Cobbett did not like what he found.

Farm workers had sunk into poverty, their families were starving. Who was to blame? Cobbett was a good hater, a one-man protest movement, and he turned the full force of his anger on those whom he held responsible.

The Enclosures, begun by kings seeking to extend their hunting grounds, and completed following the 1801 General Enclosure Act, which enabled big landowners to enclose land without a Parliamentary Act, left agricultural workers deprived of common lands and grazing. Small farmers could no longer afford to pay their labourers properly.

Then came the “tax-eaters”: after the Napoleonic Wars, Parliament abolished income tax, replacing it with increases in indirect taxes to pay the interest on the national debt. These taxes fell on necessities for which there was an inelastic demand: salt, hops, malt, tobacco, sugar, beer, and tea, shifting the burden of taxation from the middle classes to the poor, with small farmers paying proportionally more tax than higher economic groups and unable now to pay their labourers at all. Their fields were neglected, and crops went ungathered. The decline in production caused higher prices for food. Small farmhouses and labourers’ cottages, whole hamlets, and villages, fell into disrepair. Big “bull-frog” farmers gradually swallowed up the smaller ones. Rapacious landlords evicted tenants. The “bullfrog” farmers, unlike those of old, no longer fed and lodged their workers, for it was cheaper to pay them wages: wages which were inadequate for their basic needs. And such former agricultural labourers who were now unable to find work on the land at all were employed by the parish at stone breaking to build new roads for the benefit of those big farmers and landlords.

Cobbett was not convinced of the need to service the national debt, and he loathed the stockbrokers and jobbers, bankers, financiers, and fundholders, parasites who took everything and produced nothing. Moreover, he noted that taxes were also being used to support the “deadweight”, the “half timers”, army officers on half pay but with no duties, and the standing army which in peace time was used, not against a foreign threat, but against impoverished people seeking redress as at Peterloo:

One single horseman with his horse costs 36s. a week…that is more than the parish allowance to five labourers’ families at five to a family…so the one horseman and his horse cost what would feed twenty five of the distressed creatures… take away the army which is to keep distressed people from committing acts of violence and you have, at once, ample means of removing all the distress and all the danger of acts of violence.

Adding to the “deadweight” were the tax gatherers themselves, the sinecurists with their government jobs, and Anglican parsons. Cobbett did not care for parsons, “sponging clergy”: they took the revenues of their livings, subsidised with tithes and the rent from glebes, but were absentee clergymen, not even living in the parish. Nor did he care for those who issued religious tracts “which would if they could make the labourer content with half starvation.”

And then there were the Corn Laws, restrictions on importing corn and other foodstuffs to protect landowners’ interests, raising the price of bread for an already impoverished population. Potatoes, cheaper than bread under the impact of the Corn Laws, were a particular anathema to Cobbett, as was tea, replacing beer as cottage brewing declined. Potatoes were in Cobbett’s view “debilitating fare” and “soul degrading.” Tea was “a destroyer of health, an enfeebler of the frame, an engenderer of effeminacy and laziness, a debaucher of youth and a maker of misery for old age.” His own preference was for the traditional three Bs – bread, beer, and bacon, and he would regularly set off on his rides with a bacon sandwich in his coat pocket for breakfast. Frequently the bread and meat would be handed over to a hungry soul whom he met along the way.

The Trespass Act and Game Laws, protecting the hunting rights of landowners, also raised Cobbett’s ire. For they forbade the “poaching” of wild animals, even rabbits, on the landowners’ estates thus depriving the local community of food they desperately needed. Moreover, mantraps were set to catch the “poachers” and punishments included imprisonment and transportation.

Cobbett hated the middlemen too, the dealers and shopkeepers who had replaced the old country fairs and markets, and who produced nothing but added to the cost of living.

He yearned for a return to cottage technology independent of wage labour and the capitalist market which saw the accumulation of capital in ever fewer hands. Big farmers and landlords were “conspirators against labour,” capitalist agriculture had proletarianized the farm workers,

Is a nation made rich by taking the food and clothing from those who create them and giving them to those who do nothing of any use? Why should the people work incessantly when they now raise food and clothing and fuel and every necessity to maintain five times their number?

While the poor creatures that raise the wheat and the barley and the cheese and the mutton and the beef are living upon potatoes, all the good food is conveyed to the tax- eaters in the Wen!

In Cobbett’s view London was a sebaceous cyst, a Great Wen, which along with lesser wens was encroaching onto the countryside, and he detested it.

But above all Cobbett hated the Establishment, “The Thing,” which presided over all this, the political, economic, military and church elites, taking the surplus value of the countryside and manipulating the markets to their own advantage. Misgovernment, the unreformed Parliament was the ultimate source of all evil. In the end he hated the Whigs even more than the Tories because their hypocrisy was the greater.

William Cobbett warned that rural poverty would lead to riots, and he defended agricultural labourers who organised public protests. He endorsed the rick burning and machine breaking of the Swing Riots in the 1830s. For why should the near starving labourers “live on Damned potatoes while the barns are full of corn, the downs covered with sheep, and the yards full of things created by their own labours.”

But whilst fully supportive of direct action, Cobbett worked for Parliamentary reform as the ultimate remedy for economic problems: he advocated the abolition of rotten boroughs and the extension of the franchise, so that radicals could be elected to Parliament where they could raise wages, repeal the Corn Laws, lower taxes, and reverse enclosures.

Following the Great Reform Act 1832, Cobbett was elected to a newly created seat in industrial Oldham. His support for the Reform Bill had been a compromise because it still left his beloved agricultural workers without the vote. In Parliament he sought to represent both his northern constituents and the southern agricultural workers. Sympathetic to the Luddites and deeply appalled by the Peterloo massacre, outraged by conditions in the factories, he nonetheless thought that the best recourse was a return to the land and self-sufficiency within an agricultural economy. And if this sounds a little odd today, we should remember that rural workers in 1835 were still the largest occupational group in England.

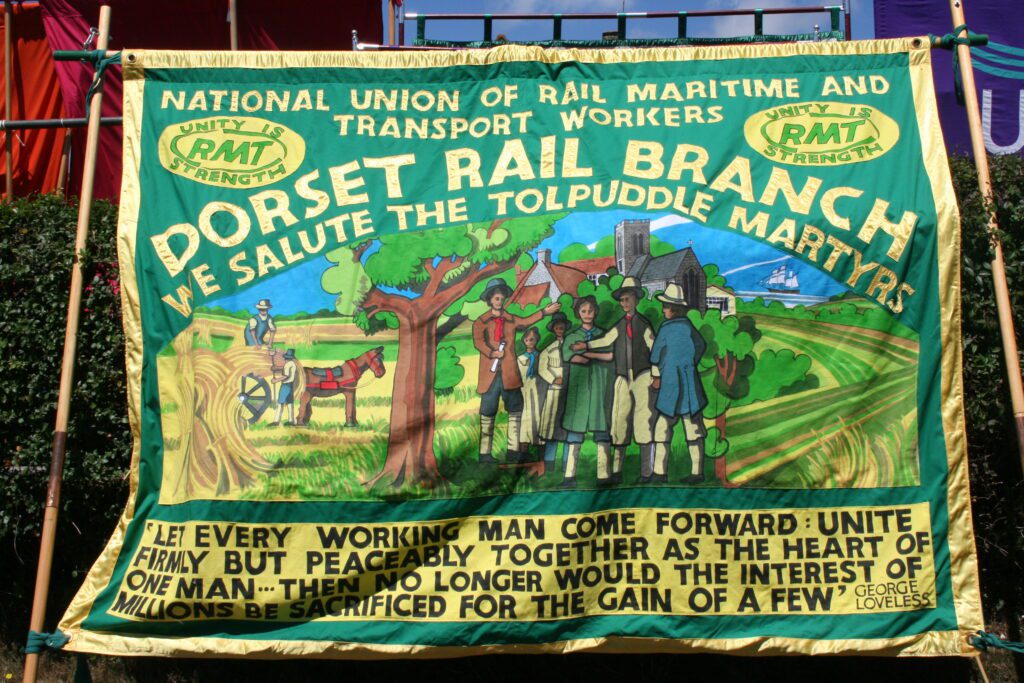

Cobbett, along with Hume and Wakley, maintained agitation in Parliament, first for the release and then for the pardon of the Tolpuddle Martyrs. He fought the brutal 1834 Poor Law Amendment which replaced outdoor payments with indoor relief: to save money all financial support for the poor was withdrawn and they were discouraged from seeking any help since their only recourse under the new system was to the workhouse, where children were separated from their parents and wives from their husbands.

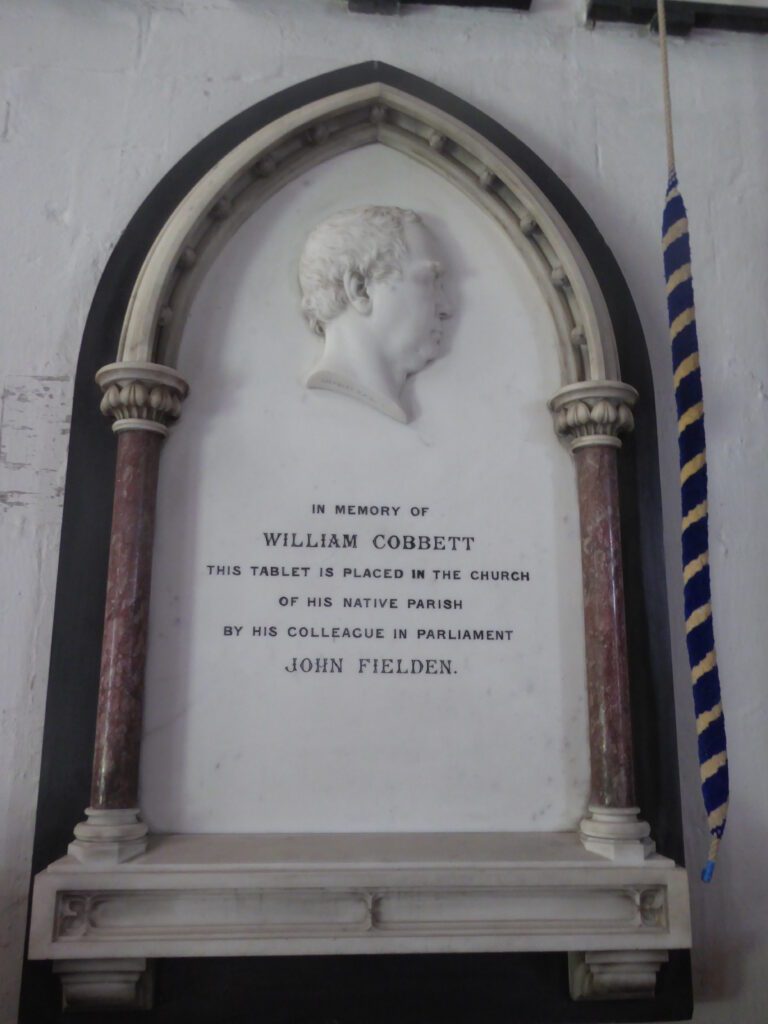

But his time in Parliament was short lived; he died in 1835 and was buried in St. Andrew’s churchyard in Farnham, the Surrey town where he was born. The following year John Russell announced an official pardon for the Tolpuddle Martyrs. The Poor Law system was not officially abolished until 1948.

It may be impossible not to smile at Cobbett’s dyspeptic outbursts against tea, potatoes, and the Great Wen. And he was no revolutionary, he had no problem with hierarchy so long as workers were fed, accommodated, had their fairs, sports, and harvest homes; his belief in noblesse oblige sits a little uncomfortably today. In the words of GDH Cole, “he was a conservative in everything except politics,” but what a magnificently angry, opinionated, choleric thorn in the side of the self-serving establishment he was.

******************

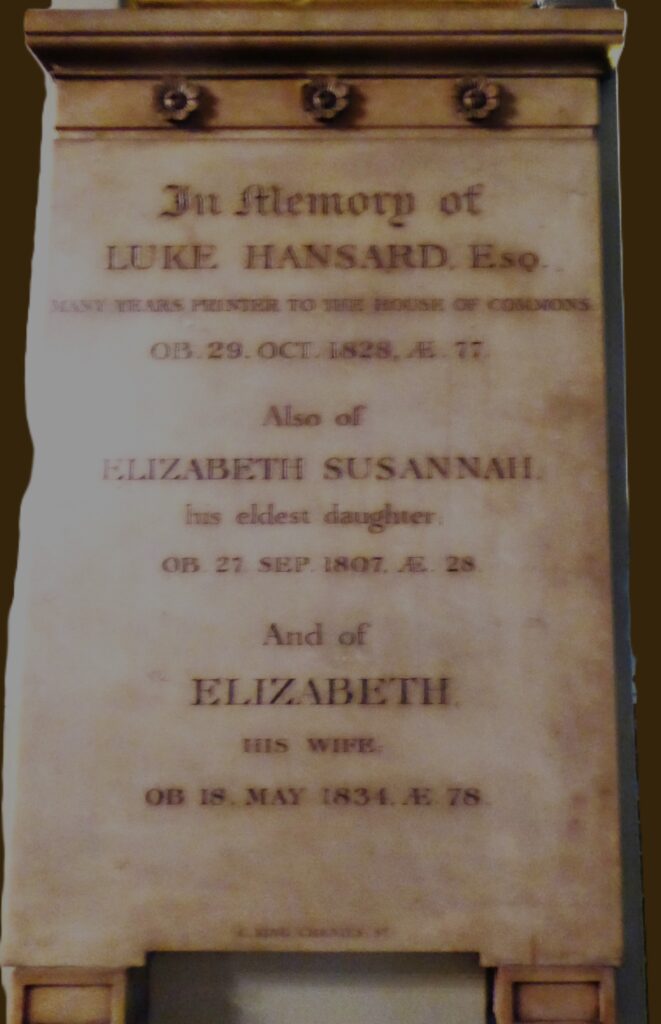

- From 1803 Cobbett was also the first person to collect and publish all parliamentary debates in Cobbett’s Parliamentary Debates. His printers were Luke Hansard and his son Thomas, who also did work for the House of Commons. In 1812 Cobbett, overwhelmed with fines for seditious behaviour, sold the publication to the Hansards who renamed it. “Hansard” remains the title of the official record of parliamentary proceedings although the family connection ended in 1889.

*******************

William Cobbett, Rural Rides, Penguin Classics, 2001. First published 1830.