Just in time for International Women’s Day on 8th March an article in The Guardian newspaper cited figures produced by the General Medical Council revealing that, with 164,440 women licensed to practise medicine in the United Kingdom, the number of female doctors had for the first time exceeded the number of males. Women now make up 50.04% of the nation’s doctors.

In 1865 there was only one female doctor on the medical register of the GMC: Elizabeth Garrett.

Born in 1836, Elizabeth Garrett had been educated at home and at a private boarding school for girls. She recorded her dissatisfaction with both her governess and her teachers, complaining particularly of the absence of science and maths teaching, although her sisters remembered that they received a sound grounding in literature and languages. After school and a tour abroad, Elizabeth returned home where for nine years she pursued her own studies alongside her domestic duties.

In 1859 she met Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman to qualify as a medical doctor in the USA. Blackwell was in London to give a series of lectures on “Medicine as a Profession for Ladies.” In a biography of her mother Louisa Garrett Anderson describes a conversation a year later between her mother, her mother’s younger sister, Millicent Garrett, and their friend Emily Davies. She quotes Davies:

It is clear what has to be done. I must devote myself to higher education, while you (Elizabeth) open the medical profession to women. After these things are done, we must see about getting the vote. You are younger than we are Millie, so you must attend to that.*

The conversation may be apocryphal, but Emily Davies went on to establish and become Mistress of Girton College, Cambridge for women students, while Millicent Garrett Fawcett led the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies between 1897 and 1919.

Elizabeth Garrett faced implacable opposition from the British medical establishment, but she had several advantages on her side: she was clever and determined, she came from a wealthy family, and her father, a successful businessman in Suffolk, was unusually supportive of his daughters’ education and of their aspirations.

Unable, as a female, to enrol at a British medical school Elizabeth took up a position as a surgery nurse at Middlesex hospital. Despite protests from the male students, she was permitted to use the dissecting room and to attend chemistry lectures. With financial support from her father, she employed a tutor to mentor her in anatomy and physiology, securing certificates in those subjects along with chemistry and pharmacy.

Despite this evidence of her commitment and ability, the medical schools continued to reject her applications.

Undeterred, Garrett continued to study with private tutors and professors, and applied to the Worshipful Company of Apothecaries seeking to exploit a loophole in their charter preventing them from excluding students from their examinations on the grounds of sex. Nonetheless they did attempt to reject her application, backing down only when her father threatened to sue them. In 1865 Elizabeth Garrett obtained her licence from the Company. Though not a medical degree, the licence did qualify her to practise medicine, and her name appeared on the register of the GMC. The Worshipful Company took immediate steps to amend their regulations, disallowing anyone privately educated from sitting their examinations in the future.

Yet though she was now qualified Garrett could still not, as a woman, hold a post in any hospital. This time her father’s backing enabled her to open her own practice and a dispensary for women and children which became The New Hospital for Women and Children.

In 1870 she finally obtained a full medical degree from the faculty of medicine in Paris which was beginning to admit women.

Members of the medical patriarchy did their best to discourage other women from following her example. In 1874 the psychiatrist Henry Maudsley claimed that education for women led to over exertion which would reduce their reproductive capacity and render them liable to nervous and mental disorders.** Edward Hammond Clarke asserted that:

Higher education in women produces monstrous brains and puny bodies, abnormally active cerebration and abnormally weak digestion, flowing thought and constipated bowels.***

According to these physicians the trinity of menstruation, pregnancy and menopause rendered women frail, unstable and unsuitable for public life.

Garrett responded that the danger for women came not from education but from boredom in the home.

In 1874 Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (she had married in 1871) cofounded the London School of Medicine for Women (later the Royal Free Hospital School of Medicine) where she lectured. Here women were prepared for the medical degree of London University whose examinations were opened to them from 1877.

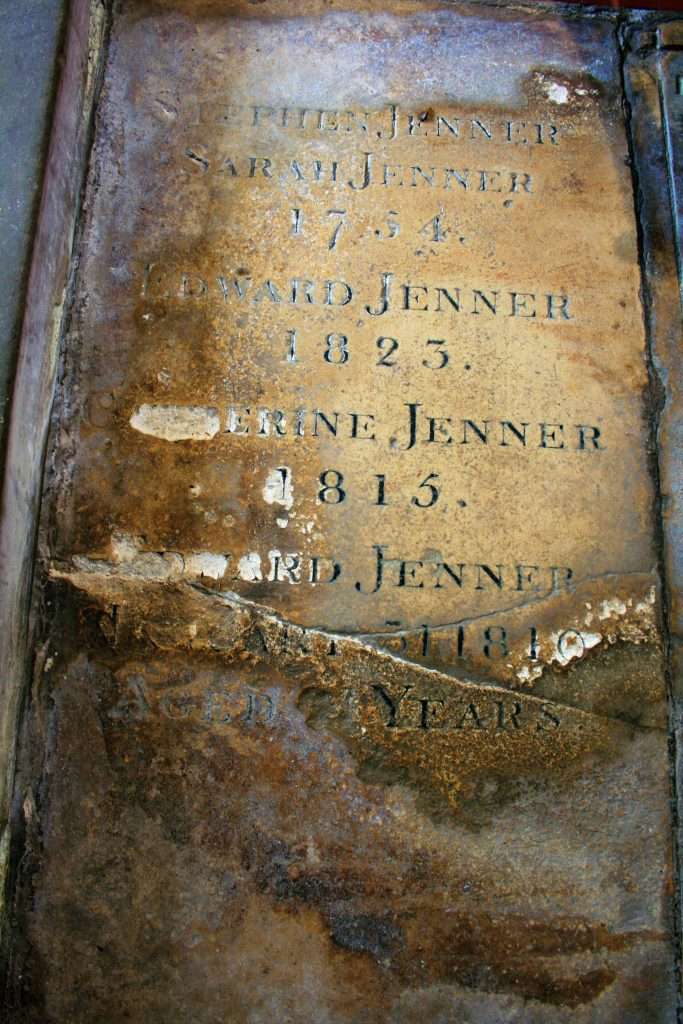

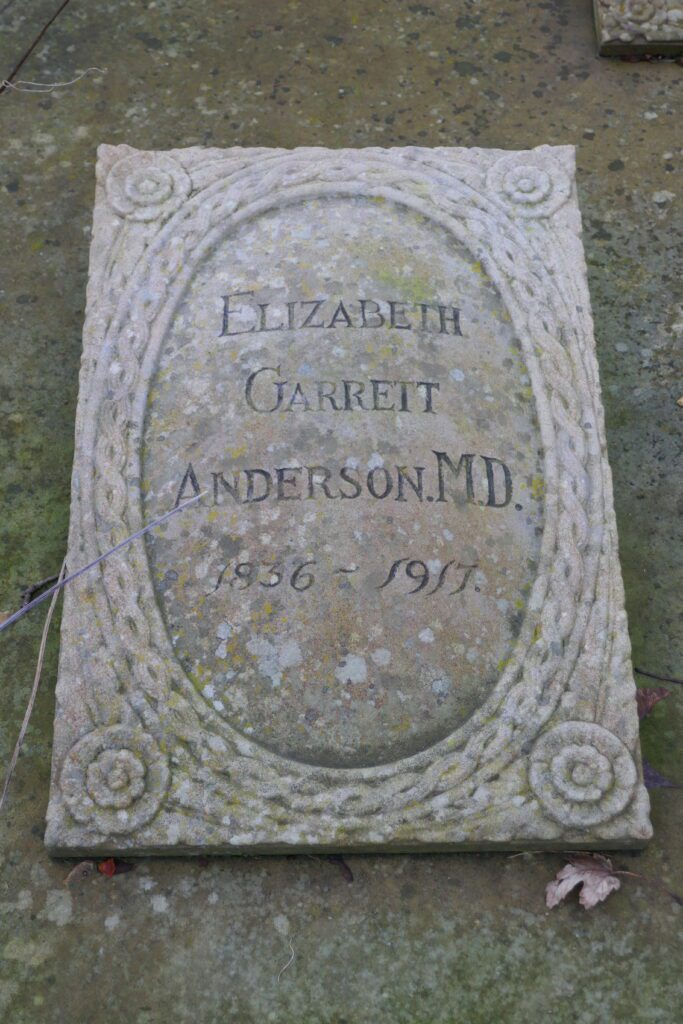

Garrett Anderson retired to her old family home Alde House, in Aldeburgh in 1902. She is buried in the family grave in the churchyard of Saint Peter and Saint Paul.

While lauding the achievements of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and the other early pioneers, I had reservations about the triumphalist tone of the newspaper article: it seemed an old and long settled battle to be reviving. But days later a letter appeared in the same newspaper from an emeritus professor at St. George’s Hospital Medical School describing a study he had published with a colleague in 1985 showing that secret quotas still existed in all the London medical schools limiting the number of women admitted to study medicine. The use of discriminatory practices only ceased in the UK in 1988 as a result of this study. **** Not such an old battle then, and as Professor Collier points out, it still took forty years to achieve today’s gender balance.

*Louisa Garrett Anderson, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson:1836-1917, Faber and Faber, 1939

**Henry Maudsley, Sex in Mind and Education, Fortnightly Review, Volume 15, April 1874

***Edward Hammond Clarke, Sex and Education, 1875

****Joe Collier, Guardian letters page, 10 March 2025