At the end of my street stands Church Farm House. There is no farm today, but in the late nineteenth century John William Bissie Matthews was the third generation of his family to grow crops and keep livestock on the surrounding fields. John and his wife Emily Etta Matthews lived with their eight children in the four bedroomed house. Attached to the house was a cottage to accommodate farm labourers, and behind, surrounding the yard, were byres, stables, a coach house, a three storey malthouse, wash house and woodshed. Beyond lay kitchen and flower gardens.

Two of the Matthews children, Ida (b.1891) and Gwen (b. 1901), recorded their memories of their childhood and early adulthood on the farm and in the village of Norton Saint Philip.

They attended the village school, which children left at fourteen, or more commonly at twelve when their labour was needed. Their play area was beneath a tree on a small green between the school and the church. Ida remembered the school closing in 1900 to celebrate the Relief of Mafeking. Gwen recalled her misery at being set to knit kettle holders and socks, and to sew aprons which were sold once a year around the village. When their brothers, who had to take the cows to the fields before school, arrived late they were caned. Children coming from the hamlet of Hassage walked two miles each way across fields and along a sunken lane bringing their lunch with them.

The same school building is still in use today for infants and juniors. It has its own playing fields, its gates are firmly locked, and the green where Gwen and Ida played is eroded by the twice daily assault of a crush of cars as parents convey their children between home and school.

Monday at Church Farm was washday, when the wife of one of the labourers would light the boiler to heat water from the rainwater tank if it were clean enough or from the well outside the backdoor. She would boil the whites and scrub other washing on a board. After rinsing the laundry by hand in a tin bath she rung the wet clothes through the mangle before hanging them out to dry in the garden. It was a full day’s work.

According to their age the children had their own weekly tasks: milking cows, scouring milk pails, straining the milk through muslin cloth, scrubbing tables, cleaning knives, polishing brass, peeling potatoes.

“On the milestone near our house was “London 108 miles” and I wondered if I would ever get there,” wrote Gwen. It must have seemed a world away to most of the villagers, when even trips into Bath, a mere seven miles away, were rare. John Matthews drove a horse and cart into Bath every Friday taking produce – eggs, cheese, bacon – from the village farms to sell in town. While there he would shop for his neighbours’ needs, including the weekly delivery of newspapers for the rectory. Gwen was charged with delivering the latter and describes a household where the cook, boots, or one of the housemaids would take her to the kitchen for milk and cake.

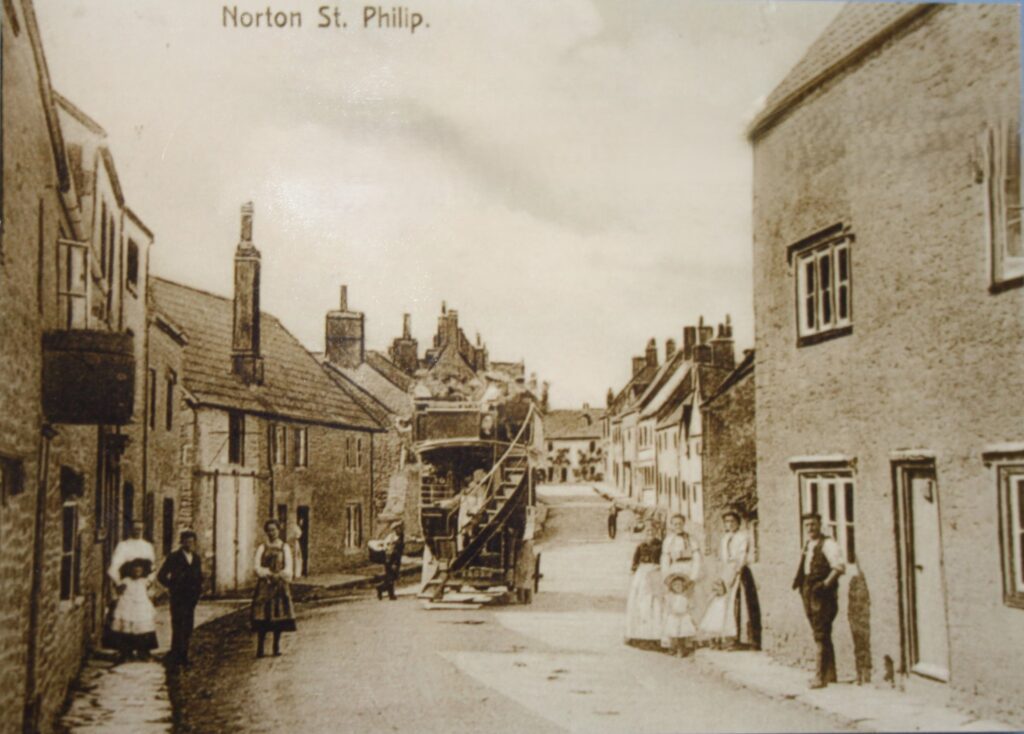

When the first motor bus arrived in the village, a double decker with no roof, the children were taken from school to see it. Ida and her friends rode it to the neighbouring village of Hinton Charterhouse…then walked back again. The bus plied between Frome and Bath but lacked the horsepower to convey its passengers up Midford Hill where they had to get out and walk. When they left school, Ida and another sister, Dora (b.1896), were apprentice milliners in department stores in Bath but the bus service was not frequent enough for them to use it, and they lived at the YWCA in Bath during the week, cycling home on Saturday afternoons and returning on Sunday evenings.

Yet if there was little contact with the wider world, the village itself throbbed with activity. Though most of the population worked on the land, there was also a corn mill and two sawmills, and Gwen enumerates two cobblers, three bakers, a policeman, a blacksmith, a wagon builder, an undertaker, a butcher, cheese and cider makers, a post office and two grocery shops. Today we count ourselves fortunate to have a Co-op store incorporating a post office counter.

The doctor, who lived in the neighbouring village of Beckington covered five villages on horseback until he acquired the first motor car seen in the area. On call twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, he held his Norton surgery in Mrs. Millet’s coffee house and shop on the Plain, made house calls, and dispensed his own medicines.

When I first came to the village in 1998, the last vestige of this service survived with a partner from the Beckington practice holding a surgery one morning a week behind the stage in the village hall. There was little question of any confidentiality, but since ailments were discussed freely and loudly in the waiting area this was immaterial. Now there are eleven doctors and a wealth of other staff in Beckington… and requests for telephone consultations may be submitted online.

Most of the village buildings which the sisters describe are still in existence albeit modified to suit new uses. On Sundays the Matthews family would fill their pew in the church, the girls peering round to compare their outfits with those of their neighbours. Externally the church is unchanged but the pews which held the Matthews and other large families are gone, replaced by a flexible, central space to accommodate meetings, concerts, playgroups.

The Old Rectory is now a private residence, with a new extension, “The West Wing.” Today’s rector is housed in a modern bungalow. There is no policeman in the Police House nor any sign of teachers in the Old School House. Manor Farm, once the grandest in the village, boasting a large staff, carriages and shire horses, has been converted into holiday lets, its barns and other outbuildings into private housing.

The Matthews knew the two pubs which still serve the village. Ida describes how “when sent on an errand we used to hold hands, hold our breath, avert our eyes, and hurry past the Fleur de Lys, an ale house on one side of the road, and the George on the other – in case we saw a drunken man because the casual labourers drank strong cider.”

More attractive to the Matthews children was Tom, the last of the heavy horses kept at the George to haul weighty loads up Bell Hill. A rope ran from the foot of the hill to a bell in the courtyard of the George. When it rang Tom would make his way unaccompanied down the hill, draw up the heavy load and return unescorted to his stable. Those using the service placed the payment of 3d in his pouch.

Recently refurbished the George now offers boutique rooms, fine dining, and a much reduced bar area, but not too many drunken men.

From the back terrace of the George the view across a field towards the church remains almost unchanged. Until well into the twentieth century cows grazed in the field, but nonetheless Gwen reports the presence of a cricket square. Today the Mead it is used purely for recreation: the cricket square is still there in summer, the bonfire in November, children play on the swings, and dogs chase balls.

Ida recalls gathering Bath asparagus in Wellow Lane and listening to nightingales there in May. There is still Bath asparagus, but even during the Covid lockdown when the village became again a place undisturbed by either cars on the roads or planes in the sky, and when I regularly met hares and deer strolling, almost tame, down the lane, and when the spring birdsong burst from the trees with no competition, I never heard a nightingale. Though I once met an old lady who told me that during her courting days she and her future husband would take blankets and lie in the fields listening to them.

At one of the periodic re-enactments of the Battle of Norton Saint Philip, the last victory for Monmouth’s rebel forces against the king in 1685, Ida was terrified by the noise and the sight of soldiers on horseback with steel helmets, waving their swords as they advanced down Chevers, locally known as Bloody, Lane. Having witnessed a similar re-enactment I can vouch for the irrational fear which even a playacting army can engender as the sound of drums and marching draws closer, and the first troops appear over the hill.

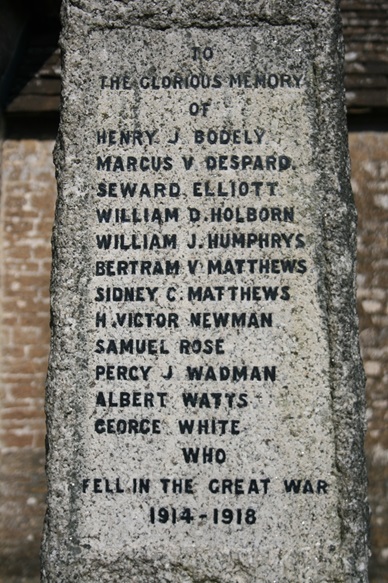

But in 1914 there was no playacting, and the Matthews time at Church Farm was ending. The two oldest brothers, Bertram (b. 1892) and Sydney (b. 1890), had emigrated to Canada but both signed up with the Canadians to fight in the First World War. They were killed within three days of each at Vimy Ridge in 1917. The younger brothers, Cyril (b. 1894) and Leslie (b. 1899) also signed up. Cyril was taken prisoner and Leslie was injured. There were no celebrations at Church Farm when the war ended.

Cyril found his way home: Gwen wrote, “Now when I look back, I think how casual we all were. Cyril came home, just walked in the back door…mother asked how he had got on to which the answer was “Alright”. Years later we learned that he had walked miles across Germany before being picked up.” Leslie was discharged from a hospital in the north with shrapnel in his foot.

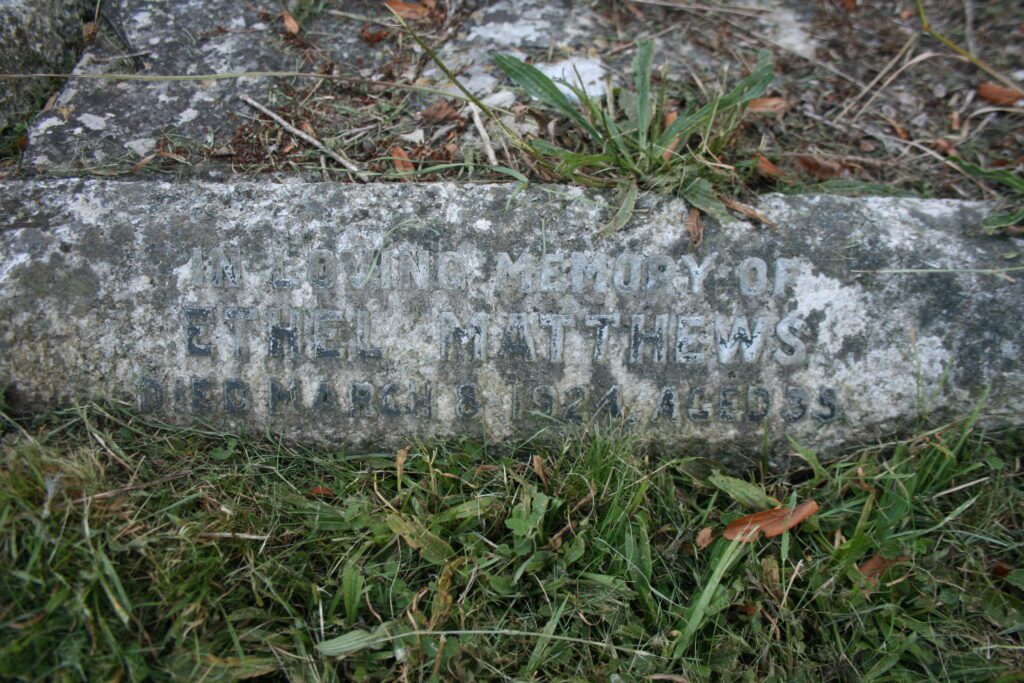

Ida had married and moved to Wales before the war began. Dora married and went to live at Row Farm in Laverton in 1920. Cyril became a farm manager in Portishead. Ethel (b.1888), the eldest sibling, who had trained as a teacher, died at home of tuberculosis in 1924. Gwen, only thirteen years old when the war broke out, had driven a lorry with two horses throughout the war years, carrying twenty churns of milk every day from Norton Dairy to Trowbridge for the London train. After the war there was no job for her.

In 1927 John Matthews retired to Wellow with his wife and Gwen. Leslie, the youngest son took over the farm for a few years before moving to another in Woolverton. Gwen married and left Wellow for Oxford in 1936.

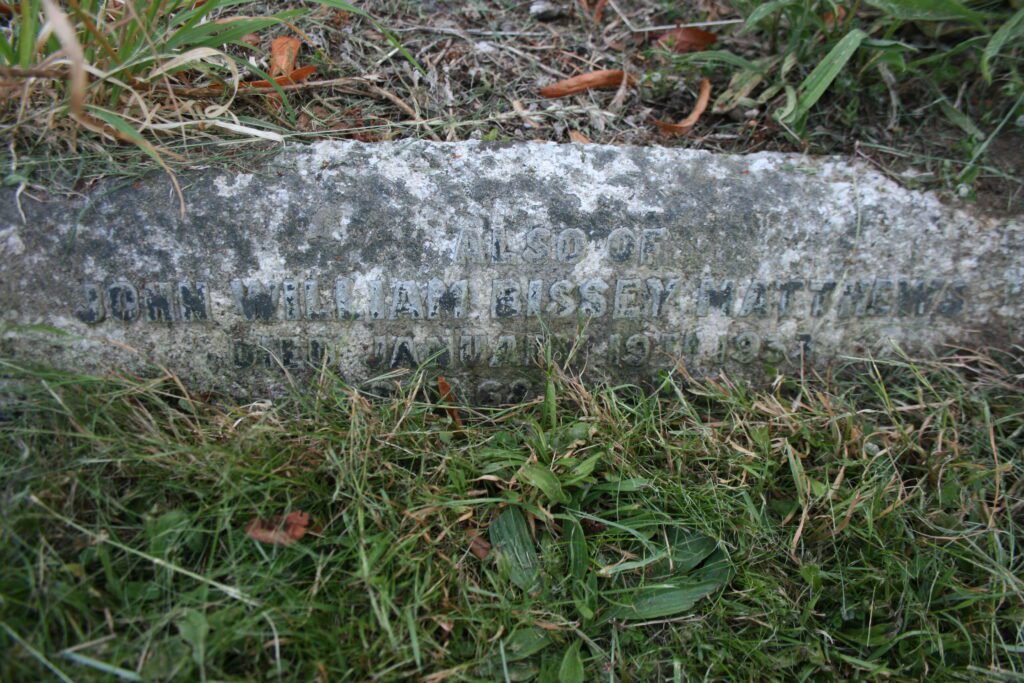

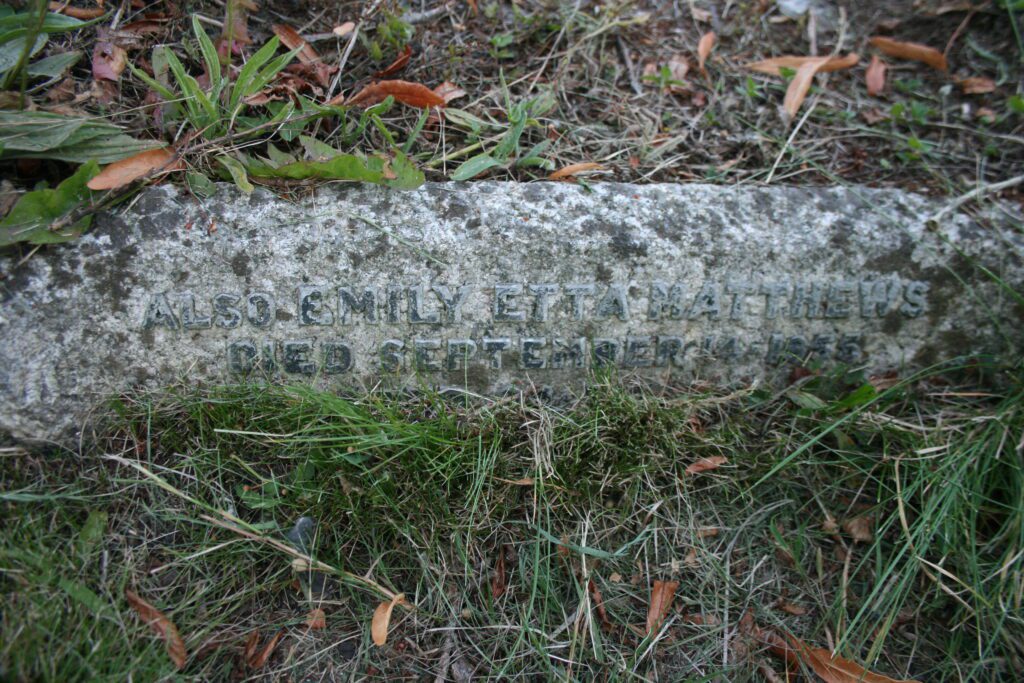

There are no farms in the heart of the village now, cars not cows move along the High Street and Church Street. Though as summer turns to autumn the combine harvesters from the outlying farms briefly dominate the roads, processing through the village with a stately, proprietary air. And the Matthews still have a presence in the village. In the churchyard Bertram and Sidney are remembered on the war memorial, while Ethel, her parents, and Dora are buried together. Viewed from where they lie, beside the church and looking across the Mead towards The George, their village is not so much changed.

See Gwen Harries – Memories of Norton Saint Philip 1902-1930

Ida Matthews – Memories of my early childhood until the age of 15