Southwark is my favourite Cathedral, not least for the warmth of the welcome always extended by the volunteer guides. It was one of them who first introduced me to Doorkins Magnificat. Leading the way to the Bishop’s Chair he indicated a tabby cat comfortably asleep on the cushion. “I always have to check on her” he whispered, “the first thing my wife asks me when I get home is ‘how was Doorkins today?’” Doorkins, he explained, first appeared at the south-west door of the cathedral in 2008. Named by one of the vergers, she was timid at first but after a few weeks of being fed decided to make the cathedral her home, sleeping there by day and prowling Borough market by night. “At Christmas,” my guide continued, “she likes to sleep in the straw around the nativity scene.”

Doorkins lived at the cathedral for eleven years and if the vergers and clergy cast their bread upon the waters in offering her hospitality and sanctuary, they were more than repaid. For Doorkins not only brought joy to her carers and visitors, but she also developed her own successful line of merchandise in the gift shop, with cards, mugs, mouse mats, fridge magnets and her own book. She was a philanthropist too, donating the food and treats which her many admirers left, and which far exceeded her own needs, to Catcuddles, a cat rescue organisation pairing unwanted cats with loving homes.

Towards the end of 2019, as Doorkins grew old, suffering with kidney problems, failing sight and hearing, she retired to the home of Paul Timms, the head verger, where almost a year later she died peacefully in his arms .

Meanwhile the cathedral had been seeking another cat to keep its mouse population under control and on 30 September 2020, the very day that Doorkins died, a stray from Catcuddles arrived at Southwark. He was called after Dr. Johnson’s cat, Hodge, and in a short video Paul Timms recounts the story of how when Boswell remarked that Hodge was a fine cat, Johnson responded “yes, sir, but I have had cats whom I liked better than this” but seeing Hodge’s reproachful look, he added hastily “but he is a very fine cat, a very fine cat indeed.”

A month after her death the clergy and vergers held a Thanksgiving service for Doorkins in the cathedral. It was live streamed because the pandemic lockdown meant that only thirty people were able to attend. A few voices were raised in criticism that a service should be held for a cat mid pandemic. The Dean, Andrew Nunn, responded gently in his eulogy, saying, “She arrived, she entered, and we made her welcome. People concluded that if this little cat is welcome, maybe I am too,” and he continued modestly “She did more to bring people to this place than I will ever do.”

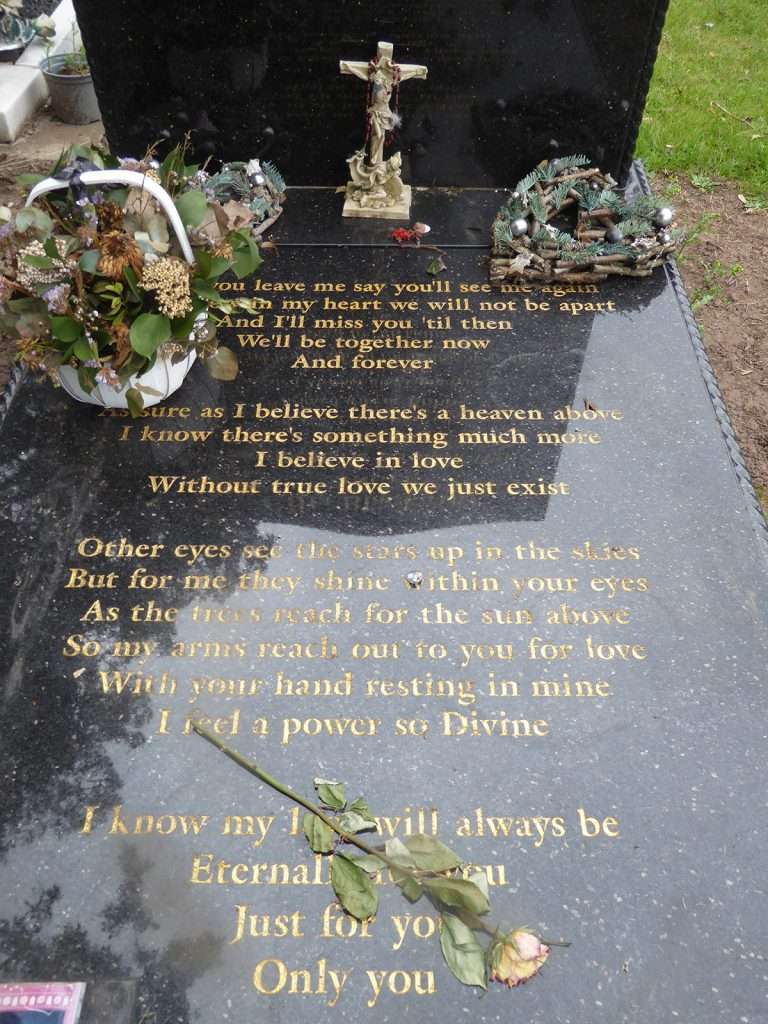

Last time I visited Southwark I met Hodge proudly patrolling the cathedral aisles, and he is, like his namesake, a very fine cat indeed. And in the churchyard beneath a wall separating the cathedral garden from Borough market I found Doorkins in her final resting place.

Southwark will always be Doorkins’ Cathedral but Hodge, and the rest of us, are very welcome.