As the long-wet days of July dripped seamlessly into August I began a cull of the bookcases. This is slow work, for potential sacrifices must be granted the dignity of a last read before they make their final journey to the Oxfam Shop. Often this results in a reprieve when forgotten qualities and nuances not previously appreciated are discovered. The task is further slowed when I am distracted by an old friend inviting me to turn its pages again, to read and to remember, and by the time I close the book and replace it, the day has passed, the light faded, and my labour no further advanced.

I took down an old Penguin paper back, its pages yellowing with age, priced in its 1964 reprint at 3/6d. Our English teacher had encouraged us to buy these editions and their faded orange spines are scattered amongst the novels on my shelves, the price not varying as I progressed through school in the mid and late sixties. Cider with Rosie was something of a cult book at the time, I think every girl in my class read it, and it met with universal approval.

I recalled a nostalgic account evoking the simplicity and innocence of a rural world in the aftermath of World War I; an autobiographical chronicle of a blissful lost idyll; a soft focused, sunny, beguiling picture of life in the village of Slad in Gloucestershire. The blurb on the back of the book seemed to confirm my impression, sounding itself a little quaint today. “Cider with Rosie” it reads “puts on record the England we have traded for the petrol engine.” This tuned with the gentle melancholy I associated with Laurie Lee’s reflections, written years later, on his childhood memories.

At first the book confirmed my recollections: in 1918 when Laurie Lee, his mother and siblings moved there, Slad was indeed a lost domain, isolated from the world, its inhabitants’ horizons confined largely to home, their only transport the horse and cart. Lee conjures a world of homely cottages, “snug, enclosed and protective” set in the hillside “like peas in a pod,” and of cottage gardens: “syringa shot up, laburnum hung down, white roses smothered the apple tree, red flowering currants spread entirely along one path: such a chaos of blossom as amazed the bees and bewildered the birds of the air.”

He charts a poetic journey through the changing seasons. In winter, “there were jigsaws of frost on the window. The light filled the house with a green polar glow; while outside there was a strange hard silence, …it was a world of glass, sparkling and motionless. Vapours had frozen all over the trees and transformed them into confections of sugar,” and there was carol singing in the snow with candles in jam jars. The summers were spent roaming the fields: “The grass was June high and had come up with a rush, a massed entanglement of species, crested with flowers and spears of wild wheat, and coiled with clambering vetches, the whole of it humming with blundering bees and flickering with scarlet butterflies.”

The Annual Church Tea and Entertainment, the charabanc outing to Weston-Super-Mare where the children played on the beach and peered into the penny slot machines, leap off the pages, intense, vivid, gleeful events.

Poverty, dirt, and limited horizons are treated lightly, met with humour: a pump supplies water and wood fires are used for cooking and heating water for the shared bath – “being the youngest but one my water was always the dirtiest but one.” The hungry children tore apart “fresh loaves with crusts still warm, their monotony brightened by the objects we found in them – string, nails, paper, and once a mouse; for those were days of happy-go-lucky baking.” In the two roomed village school – “universal education and unusual fertility had packed it to the walls with pupils” – one teacher and her young assistant taught every child in the valley from four to fourteen.

And at the book’s heart he recounts the perfect first flirtation, the perfect first kiss, with Rosie. “It was a motionless day of summer, creamy, hazy, and amber coloured, with beech trees standing in heavy sunlight as though clogged with wild wet honey.…we went to the bottom of the field, where a wagon stood half loaded. Festoons of untrimmed grass hung down like curtains all around it. We crawled underneath, between the wheels, into a herb-scented cave of darkness.” They drank from the squat jar of cider and, “For a long time we sat with our mouths very close, breathing the same hot air. We kissed, once only, so dry and shy, it was like two leaves colliding in air.”

As he reveals the changes that began to encroach during the later part of his childhood, destroying forever that guileless world, it is impossible not to share his regret, impossible not to want to reach out and hold on, to draw back all that is lost. The motor cars and the bicycles took the young away from the village, the expanding towns drew nearer, the clothes people wore and the very language they spoke moved into line with the wider, modern world. “The old people just dropped away – the white-whiskered, gaitered, booted and bonneted, ancient-tongued last of their world, who had thee’d and thou’d both man and beast, called young girls damsels, young boys squires, old men masters.”

But beyond the poetry I discovered something I had forgotten, for Laurie Lee did not view the past through a glass darkly, and alongside the joyous celebration of his childhood world he reveals the bigotry, casual cruelty, danger, and disease which blighted the lives of the villagers.

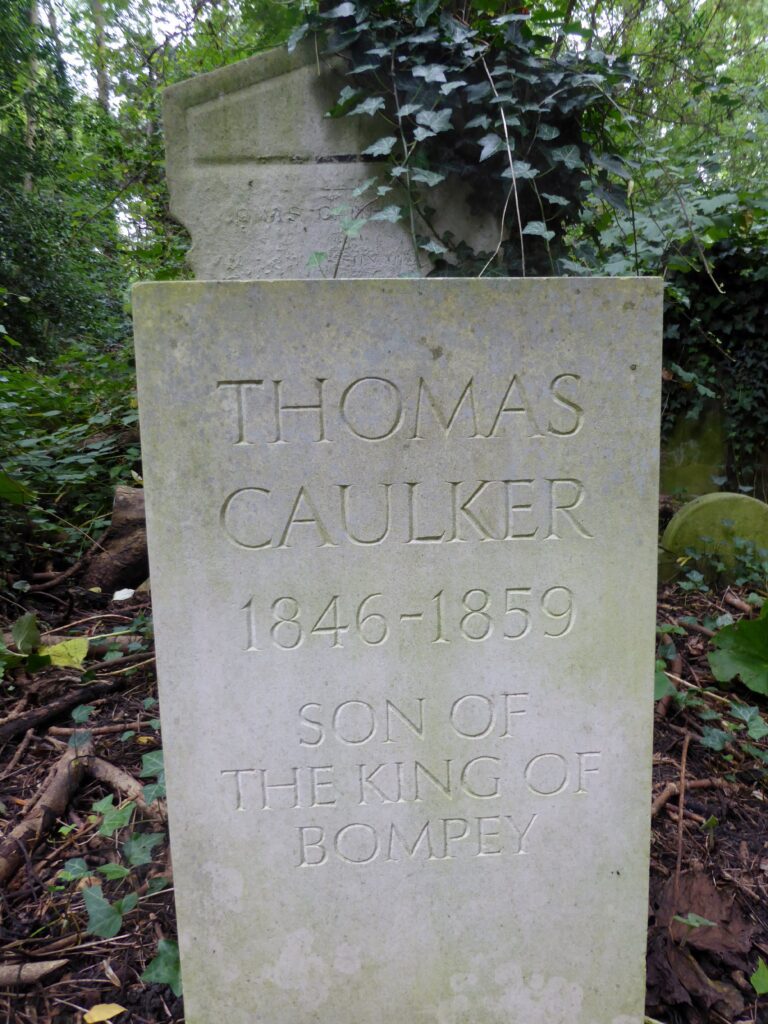

For this is a world where infant death is commonplace: “in those cold valley cottages, with their dripping walls, damp beds and oozing floors, a child could sicken and die in a year,” and a heartless church will not bury the unbaptised infants in consecrated ground, so that “tiny, anonymous graves were tucked away under the churchyard laurels, where quick dying infants – behind the vicar’s back – were stowed secretly among the jam-jars.”

This is a world where old folk remember the gibbet at Bulls Cross, and Laurie and his friends play in a ruined cottage at Dead Combe Bottom where “behind the door, blood red with rust, hung a naked iron hook.” This, they learn, was the home of the hangman who, during the hungry times when local felons flourished, worked busily by night in darkness. One night he dispatched a shivering boy and as the cloud moved from the moon recognised his son. He went home, fixed a noose to the iron hook, and killed himself.

It is the world of ugly superstition and desperate tramps, halfwits, a deaf mute beggar “with a black beetle’s body, short legs, and a mouth like a puppet, soft boiled eyes” of whom it was said “he could ruin a girl with a glance, take the manhood away from a man, scramble your brains, turn bacon green,” so that when he approached the village “food was put out on the top of walls and people shut themselves up in their privies.”

It is a world in which a vicious murder can be absorbed into the fabric of everyday life. A lad who had been shipped off to the colonies, a common fate for poor boys, returns successful and richly dressed boasting of his success, contemptuous of the tenant farmers and their miserable wages, scornful of their narrow lives and their servility. In the village pub he buys round after round of drinks while he flaunts his achievements, and “when the public house closed the New Zealander was the last to leave. When he reached the stone-cross the young men were waiting, a bunched group, heads down in the wind. They hit him in turn. Beat him bloodily down in the snow…beat him for the sake of themselves. Then they emptied his pockets, threw him over a wall and left him. He was insensible now… the storm blew all night across him… and in the morning he was found frozen to death.” But the young men “were not treated as outcasts, nor did they appear to live under any special stain. They belonged to the village and the village looked after them”.

It is a world of tragic suicide. The grief stricken, half mad Miss Flynn who has “been bad” kills herself one night: “naked, alone in the night … she slipped into (the village pond) like a bed and drowned quietly away in the reeds.. a green foot under, still and all night by herself, looking up through the water as though through a window…her hair floating out and her white eyes open.”

It is the world where half a dozen bored, aimless young men casually plot to rape “mad Lizzy”, a simple-minded girl of sixteen with “a stumpy accessible body.” That Lizzy responds to the first tentative touch by hitting her would be assailant with a bag of crayons before walking away unharmed, renders the ugly intention no less sickening.

It is a world where the shadow of the workhouse is always present. “The Workhouse – always a word of shame, grey shadow falling on the close of life, most feared by the old, abhorred more than debt, or prison, or beggary, or even the stain of madness”. Frail, sick, and old, the devoted Joseph and Hannah Brown “white and speechless were taken away to the Workhouse” by the “kind, killing Authority” which labelling them too frail to care for themselves separated them for the first time in fifty years, Hannah to the women’s wing, Joseph to the men’s wing of the merciless institution. “They did not see each other again for within a week they were both dead.”

There was a darkness interwoven with the beauty of the Slad Valley, and Laurie Lee’s book is something more powerful and complex than the bucolic, nostalgic celebration which I had remembered.

Yet Laurie Lee never lost his great love of the steep sided valley, and with the success of his books he bought a cottage in Slad near his childhood home where he lived until his death in 1997.

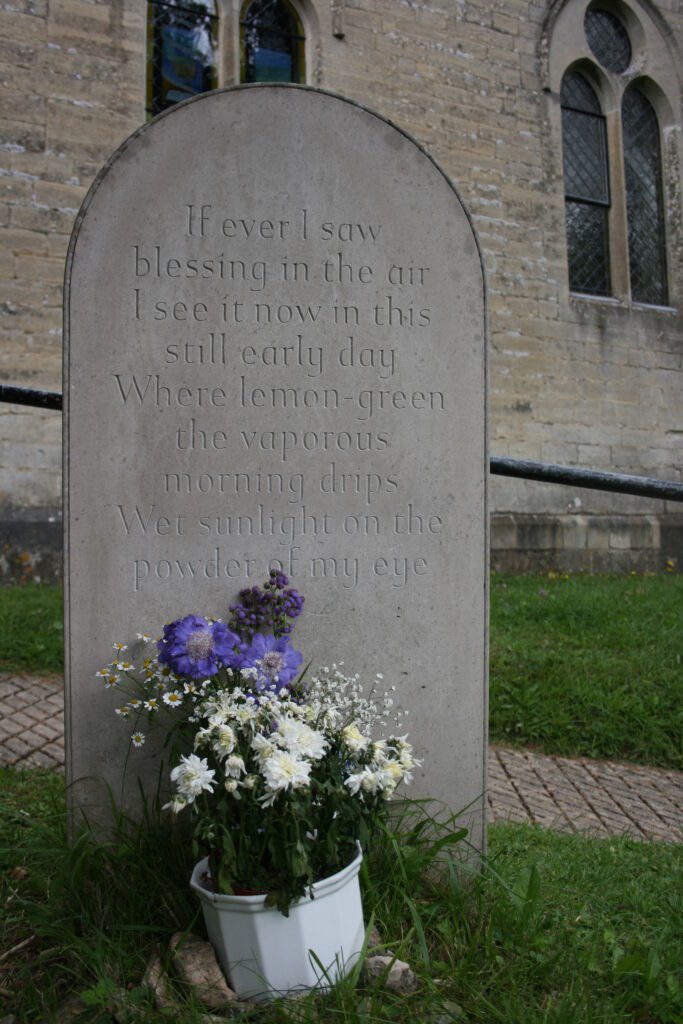

He had chosen his place in the churchyard, located between the church and The Woolpack Inn. On one side his stone reads, “He lies in the valley he loved.”

On the other the first lines of his poem April Rise are recorded:

If ever I saw

blessing in the air

I see it now in this

still early day

Where lemon green

the vaporous

morning drips

Wet sunlight on the

powder of my eye.

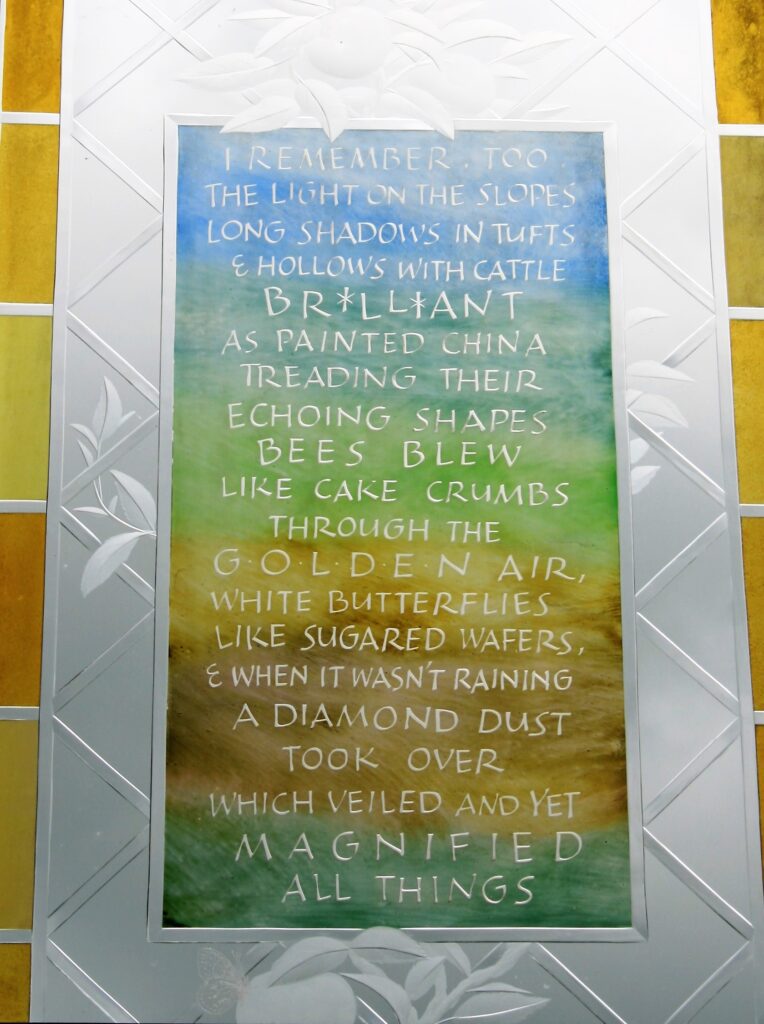

In the church a memorial window features his violin, signature, a map of Spain and an extract from Cider with Rosie.

Bees blew

like cake crumbs

through the

golden air,

white butterflies

like sugared wafers

An afterthought

If you visit Laurie Lee in Slad, cross the road to The Woolpack where you can buy the books and where the food has been enthusiastically reviewed by no less a person than Grace Dent:

www.theguardian.com>food>2023 The Woolpack, Slad, Gloucestershire: “Fancy but hearty food.”