I suspect that in every generation sexagenarians glance wistfully over their shoulders and peer through their rose-coloured spectacles, bringing into fuzzy focus the years of their youth, inevitably a time of hope and optimism, when everything was lighter, brighter, and more exciting. But surely this temptation has never been greater than for those of us who grew up in the Swinging Sixties. The soubriquet was not some post hoc addition, for even at the time it was in use, applied especially to Swinging London with its psychedelic fashions, Carnaby Street and Biba, and the London Sound: The Rolling Stones; The Who; The Kinks. London swung, it led the world – effortlessly.

Even in the provinces the glamour rubbed off. As I walked through the town to school each day, it was as though I were walking through a theatre with spotlights being switched on all around me. The grey-drab fifties were receding before an onslaught of colour. No more the dirty yellow smog, no more soot-stained buildings, no more bomb sites and derelict houses. Every day brought change: bomb sites were cleared, skips appeared outside empty houses, fresh paint brought shop fronts to life and boutiques mushroomed throughout the town. My previously monochrome world was transformed into a glorious technicolour environment.

After school we headed to Granny’s Garden, our favourite boutique, where the young shop assistants perused the rails of mini-skirts, skinny ribbed jumpers, lace blouses, feather boas, ponchos, PVC raincoats and velvet jackets as eagerly as we did, and no one minded how many outfits we tried on in the communal changing rooms. We would emerge in our finery and bop around the shop, casting covert glances at ourselves in the many mirrors, as the latest pop music pulsated through the building. And no one seemed to care if, as was commonly the case, we left without making any purchases.

A far cry this from the two prim department stores which had previously held a monopoly as purveyors of frocks. Their air may have been headily scented, but such a pall of silence prevailed that we had automatically lowered our voices to a whisper on entering. Middle-aged assistants guarded goods behind counters and clothes from the few racks were surrendered reluctantly with a careful counting of hangers.

Discos replaced dances: you could tell the difference because the music was louder and faster, a disco ball reflected the lights, and the over thirties gave us a wide berth.

No pop star epitomised this emergence from the chrysalis of the fifties as vibrantly as Dusty Springfield. With her abundant blond bouffant; panda-eyed with heavy black eye liner, eyeshadow, and mascara; her makeup completed with a pale pink lipstick; and all this sitting atop glittery, sparkly, frilly dresses, she was the Swinging Sixties, the glamorous girl we all aspired, hopelessly, to be. With a breathy sensuality which struck envy into our hearts, her songs accompanied us through the sixties: “ I Only Want To Be With You;” “You Don’t Have To Say You Love Me;” “Son of a Preacher Man.”

And yet, and yet, if I remove my pink spectacles and turn to face the sixties head on, was it all quite so bright and shiny?

Even before Kate Millett took us by the hand in 1970 (the year of the publication of Sexual Politics) and guided us towards an understanding of Modern Patriarchy, articulating the need for a Second Wave of Feminism, jarring notes were already penetrating our consciousness.

Casual sexism labelled young women “dolly birds” or just “ birds.” Infantalising and undermining, the derogatory terms implied that an interest in clothes and makeup was incompatible with intellect. Meanwhile, even in academic schools, it was not unusual for a cohort of girls to leave at sixteen to go to secretarial college. One of my friends took this route and subsequently hosted a party peopled mainly by her new college friends and their soul mates, The Young Farmers. After one of the latter had tried, unsuccessfully, to stick his tongue down my throat, he informed me: “It’s not very attractive for a girl to have too many O-levels. Girls should concentrate on looking attractive, getting married and entertaining for their husbands.” Too my shame I was left speechless. A short-lived boyfriend, with the air of one who considers himself emancipated, opined “I approve of women working…except when the children are young of course.” A friend’s father eyeing his daughter and me ruefully, expostulated: “But what will you girls do if you meet millionaires on the tube tomorrow, and they ask you to marry them, and you have to admit that you can’t cook?” We rolled our eyes at each other: there were just too many non sequiturs there for us to engage with the question at all.

Even after the 1967 Family Planning Act, GPs were often reluctant to prescribe the pill for unmarried women. In the last weeks of school, a GP was called in to give us The Talk: oozing with self-importance, he left us in no doubt that it was our responsibility not to enflame the passions of young men who might not be able to control themselves, and concluded with pompous self-satisfaction that he had never prescribed the pill for any unmarried girl without insisting that she first return in the company of boyfriend and parents to discuss whether this course of action was wise. I wondered even then how many unwanted pregnancies his sanctimonious attitude had facilitated.

And when the Abortion Act, making abortion legal up to the point of twenty eight weeks gestation, came into effect in April 1968, there were still a lot of hoops to be jumped through and care was needed to give the right answers to the two doctors and the counsellor who had to be convinced that this course of action was strictly necessary.

Barbara Castle, then one of only twenty-four women in Parliament, was not able to get the Equal Pay Act passed until 1970, and then its implementation was delayed for a further five years.

Not so rosy then, life for women and girls in the sixties.

Nor for other minority groups: the Race Relations Act of 1965 failed to address issues of discrimination in housing and unemployment, and while the follow up legislation of 1968 may have prohibited overt racism, racist violence by far-right groups continued and casual prejudice against those with darker skins was widespread.

Similarly, it was not until 1967 that the Sexual Offences Act legalised homosexual practices between men over the age of twenty-one. For much of the sixties loving the wrong person could make you a criminal. Even after the act was passed widespread homophobia remained, breeding and cultivating a fear of coming out and facing discrimination in the workplace, bullying, and hate crime. And although lesbianism had never been illegal, the same prejudices prevailed against gay women.

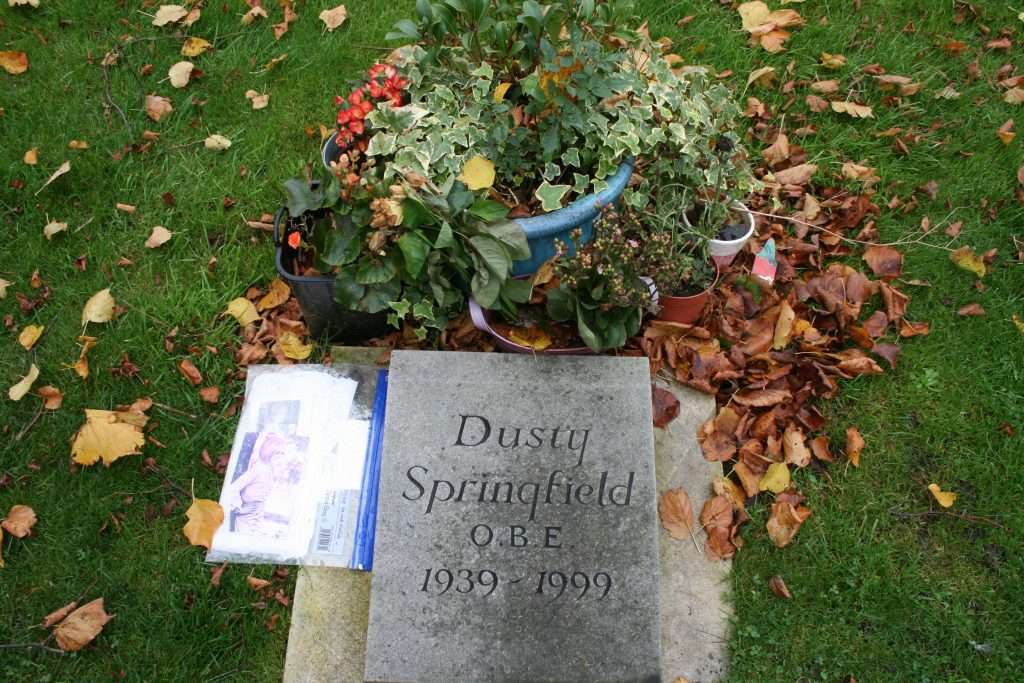

And Dusty Springfield? When I discovered her grave in the churchyard of St. Mary the Virgin in Henley it seemed a strange resting place for the sixties icon. For if anywhere in England was untouched by the Swinging Sixties surely it was Henley. As the bright comet of the sixties flashed briefly across the twentieth century sky, this compact little town with its smart shops, elegant houses, cosy old pubs facing the river, and famous regatta held annually since 1893, looked a prime candidate for being the one to conform to older, more staid and sober ways.

But if there is a marked disparity between Dusty Springfield, the embodiment of the Swinging Sixties, and the town where she rests, far more disturbing is the realisation that beneath the froth, fun, and frivolity of the sixties the dark evils of sexism, racism, and homophobia were still firmly rooted. Dusty Springfield, talented, beautiful, successful, and admired, felt obliged to conceal her sexuality, keeping her relationship with the singer-songwriter Norma Tanega quiet, and living a reclusive life for a time to avoid the scrutiny of the British tabloids. She feared the prurient media attention that would lead to loss of contracts, and her authorised biography Dancing with Demons recounts her tortured fear that it could end her career if she were exposed as a lesbian. Sadness and despair emanate from the pages of the book.

And so, despite the temptation in these gloomy days, to gaze back nostalgically at the sixties, I am resisting their lure. And if the present days lack the joyous optimism of those times, still much of the bigotry and prejudice which also characterised them, though by no means eliminated, have unquestionably declined. Swinging those years may have been, but a certain darkness lay beneath their technicolour surface.

Kate Millett, Sexual Politics, Doubleday, 1970

Penny Valentine and Vicki Wickham, Dancing with Demons:The Authorised Biography of Dusty Springfield, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 2001.