In the 60s and 70s all our secondary schools followed the same history curriculum. We began with Julius Caesar’s invasion of Britain and made our way systematically through England’s vicissitudes from 55 BC up to 1914, skimming the extreme edges of classical antiquity and contemporary history. The former was held to be the remit of the classics department, and of the latter we did not speak. My history teacher justified this on the basis that objectivity was impossible without a certain distance; my youthful cynicism judged it more likely a reluctance to engage with criticism of the status quo.

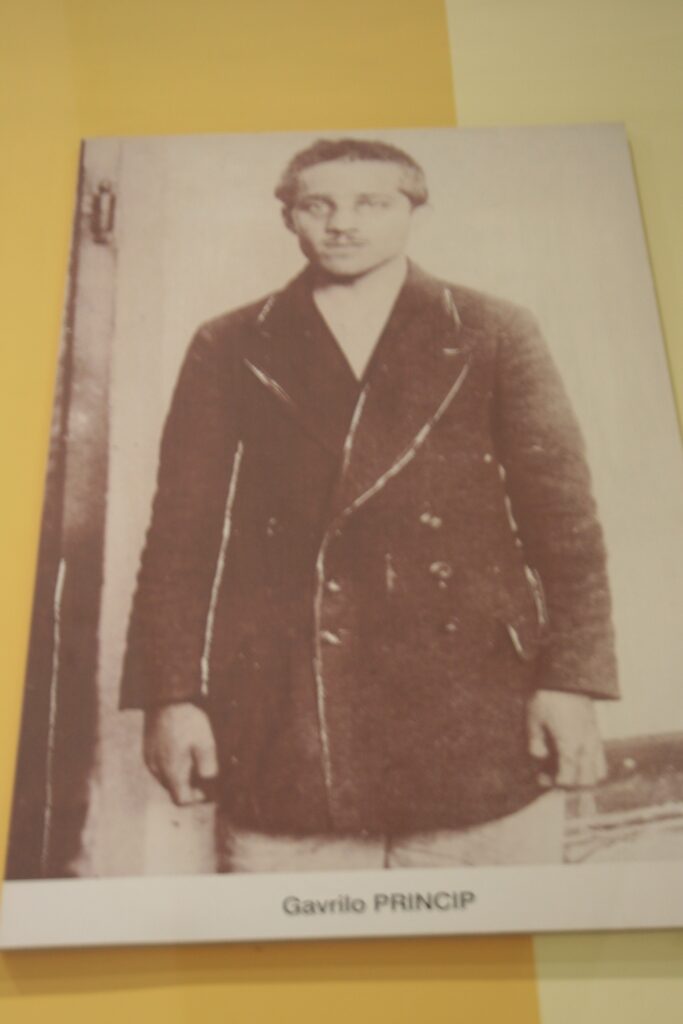

In those final history lessons in the fifth form, as we edged towards the First World War, I developed a wild enthusiasm for Gavrilo Princip. This can certainly not have been the intention of my history teacher, a firm supporter of law and order, who would without doubt have been an apologist for the Austro-Hungarian Empire against the upstart Serb from Bosnia.

But to me Princip was a romantic hero, striking a blow against Austria’s occupation of Bosnian territory in 1878 followed by its aggressive annexation in 1908. Young Bosnia was a revolutionary movement seeking to end Austro-Hungarian rule over Bosnia-Herzegovina and to establish an independent state. The political assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the representative and heir of an unelected ruler at home and a foreign oppressor in Bosnia, was entirely justified. Princip was a freedom fighter.

If there had been posters of Princip for sale in English provincial towns in 1968, one would undoubtedly have adorned my bedroom wall alongside Che Guevara.

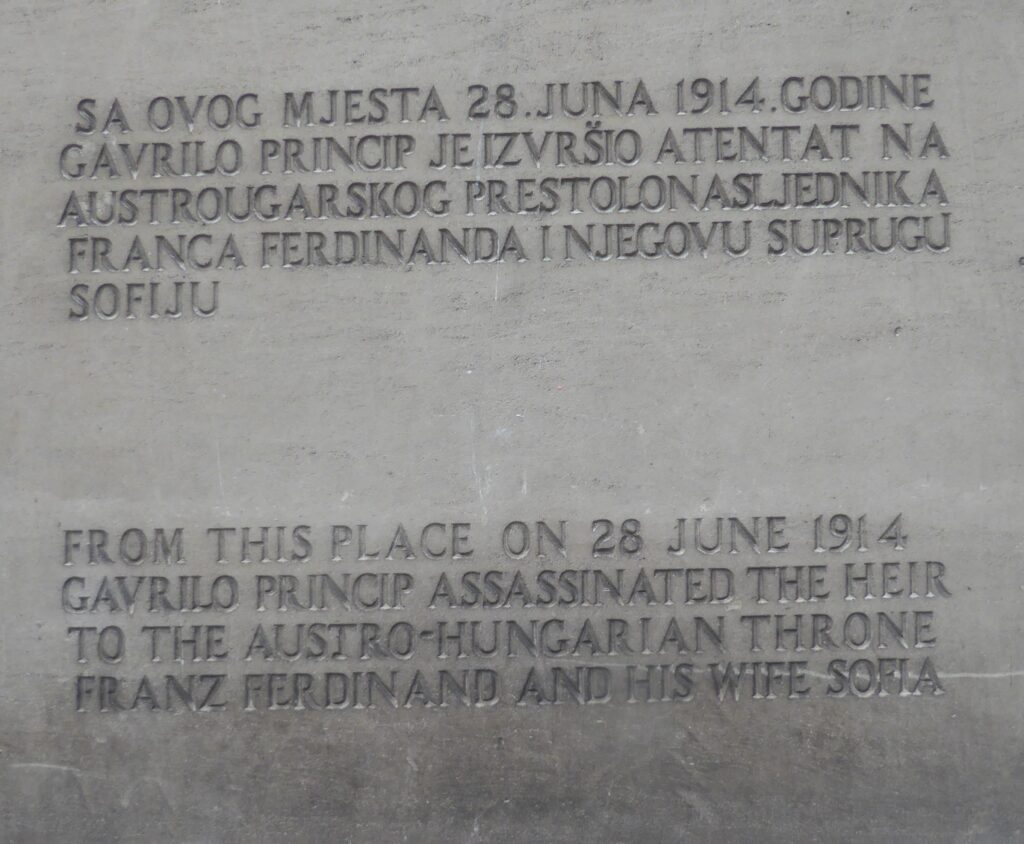

Two years ago, I visited a museum with the cumbersome designation Museum of Sarajevo,1878-1918. The dates mark the period of Austro-Hungary’s occupation, and it was from outside this building that Princip fired the shots which killed the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne. Until the collapse of Yugoslavia it had been called the Young Bosnia Museum, and Princip and his fellow members of Young Bosnia had been glorified as revolutionary idealists. Outside the museum a footprint was set into the cement to mark the spot where Princip stood to take aim at the Archduke, and there visiting Yugoslav schoolchildren used to pose for photographs.

The Museum of Sarajevo 1878-1918, located in a former delicatessen beside the Latin Bridge, formerly called the Princip Bridge.

Today, the museum’s approach is more subdued. It records the history of resistance to Austro-Hungarian oppression, and the assassination. There are clothes, photographs, and weapons on display, and two uncomfortable looking waxworks of the archduke and his wife. But the tone is factual, and the historic significance of the museum’s location is not stressed.

For the recent history of the former Yugoslavia has cast a shadow which has led to the past being rewritten in some of the former constituent republics. Under the leadership of Slobodan Milosevic ethnic cleansing of Croats took palace in those parts of Croatia controlled by Serbia. Milosevic’s ultra nationalism, his irredentist and revanchist attempt to seize Bosnia for the Serbs, combined with Radovan Karadzic’s genocidal massacre at Srebrenica, and the brutal siege of Sarajevo, have cast the Serbs in an ugly light.

And Princip has become a polarising figure: while still a hero in Serbia, he is now perceived in Croatia as a Serbian nationalist terrorist rather than a liberty loving revolutionary. He is even held responsible for the First World War rather than his actions being understood as a catalyst and excuse for further Austrian aggression.

There is no commonly held view in Bosnia. Two different versions of the truth are expounded alongside each other. School texts in predominantly Bosniak and Croat areas describe Princip as a Belgrade backed terrorist, while the children of Bosnian Serbs are taught that his cause was a just one, seeking liberation from colonised serfdom.

It is unwise to rewrite the past in the light of the present. It is true that in 1914 there was in Serbia a desire for a union of southern Slavs under Serbian hegemony, and that the Bosniaks and Croats had no desire for this greater Serbia. But Princip was no Milosevic or Karadzic, his loathing for Austrian oppression was legitimate. At his trial he argued,

I am a Yugoslav nationalist, aiming for the unification of all Yugoslavs, and I do not care what form of state, but it must be free of Austria.

Asked why he had shot the archduke he replied,

People suffer because they are so poor and because they are treated as animals. I am the son of a peasant; I know how people live in the villages and that is why I wanted revenge.

Princip risked his life for a revolutionary ideology of social justice. Austrian rule was feudal and oppressive, political opposition brutally suppressed. Moreover, the Serbian government was not involved in the assassination, and the members of Young Bosnia were drawn from all three ethnic groups in Bosnia: the Bosniaks, the Bosnian Serbs, and the Croats.

The museum, located in predominantly Bosniak Sarajevo, displays understandable discretion. But I was happy to see that Princip’s grave in the Holy Archangels Cemetery in Sarajevo still receives care. At the time of the assassination, Princip was only nineteen, a year too young to be subjected to the death penalty, so he was given the maximum sentence of twenty years in an Austrian military prison. There, chained to a wall in solitary confinement, he died of TB in 1918. In 1920 he and his comrades were exhumed and reburied below the Vidovdan Heroes Chapel. Today there are flowers on the grave, and it bears a quotation from the Montenegrin poet, Petrovic-Njegos,

Blessed is he who lives forever; he did not die in vain.