“You should come to Newport in November,” urged the lady on the Chartist bookstall at Tolpuddle, “You’ll love it.” In the height of summer, Tolpuddle was putting forth its chocolate-box best: a Dorset village of plump thatched cottages, a riot of flowers in the gardens, tea and cakes served outside the village hall, pints drunk in the pub’s beer garden, and Songs of Praise being recorded in the twelfth century church. Newport, I knew, had been a major port in the nineteenth century for the export of coal from the South Wales Valleys, but the decline of the docks had begun in the 1920s, and whenever I had viewed Newport from the train the river Usk had looked bleak and deserted, brown water flanked by huge, oozing, brown mudbanks.

This in November, one of the darkest and dampest of months? But the lady on the bookstall was adamant, enticing me with words as seductive as the Sirens’ honeyed song: “Torchlit Procession” and “Chartist Uprising.”

For Tolpuddle and Newport have a radical history in common: Tolpuddle has the agricultural labourers persecuted for attempting to form unions, and Newport has the greatest of the Chartist uprisings seeking political reform. And both host festivals to remember and celebrate those who gave their lives and their freedom to advance democracy.

Chartism rose out of bitter disappointment with the 1832 Reform Act. The latter had adjusted the boundaries of Parliamentary constituencies, removing political corruption in the form of rotten boroughs in the pockets of local aristocrats, and creating new constituencies in the cities of the industrial revolution. A very modest extension of the franchise however still left the right to vote dependent upon a substantial property qualification: only one fifth of adult males could vote and women were specifically barred. The working class had been betrayed by the middle class.

The London Working Men’s Association, and in Wales the Carmarthen WMA, were founded in 1836, and in 1838 the WMA drew up the six points of the Peoples’ Charter: a secret ballot, votes for all men over 21, payment for MPs, equal size constituencies, no property qualification for MPs, and annual parliamentary elections.

Chartism, the first mass movement driven by the working class, flourished as its members sought to implement their goals by constitutional means, believing that representation in Parliament as well as being a democratic right would also furnish them with an agency to alleviate their economic distress. Circulating Chartist papers and periodicals, they held meetings in the East Midlands, the Potteries, the Black Country, Glasgow, the north of England and the valleys of industrial South Wales where Chartism gained widespread support in the iron and coal mining villages. At contested elections Chartists gathered at the hustings where their candidates won by a show of hands but were disqualified from standing in the actual election. In 1839 they took their first national petition, signed by 1.3 million working people, to Parliament. MPs rejected the petition, and Chartists, including the leading orator Henry Vincent, were arrested and imprisoned for making “inflammatory speeches” and using “seditious language.”

Against this background, attitudes hardened and there was rioting. John Frost, a former mayor of Newport, planned the Newport Rising. Sources differ as to whether this was a peaceful protest petitioning for the release of imprisoned Chartists or an armed uprising with the aim of taking the town as the first step towards a nationwide rising. Surely both objectives must have existed in the minds of different men. Of the 10,000 who marched from the valleys of S.E. Wales, some were carrying homemade weapons. They marched through heavy rainstorms during the night of 3rd November 1839 seeking to converge on Newport from three directions at dawn on the morning of the fourth. The column from the west was led by John Frost, that from Blackwood by Zephaniah Williams and that from Pontypool by William Jones.

In Newport the authorities, informed of the marches by government spies, had already arrested local Chartists, and imprisoned them in the Westgate Hotel. Armed soldiers were also concealed in the hotel. When the first marchers arrived, they surrounded the hotel demanding the release of their comrades. No one knows for certain who fired the first shot, but when the soldiers with their superior arms opened fire, they killed more than twenty men, injuring around fifty. The Chartists were forced to retreat.

Ten of the dead were buried in unmarked graves in the churchyard of St. Woolos parish church, now Newport Cathedral. Two hundred Chartists were arrested and twenty-one charged with high treason. The three leaders were sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered, the last time this sentence was passed in England and Wales. Nationwide protests and petitions, combined with the fear of uprisings elsewhere – there were attempted risings in Sheffield, the East End of London and Bradford – led to the sentences being commuted to transportation for life.

In November 2018, on the anniversary of the rising, the first Chartist Festival was launched. Newport Rising! celebrates Chartism and seeks to inspire action and engagement in democratic processes to promote positive change, as part of the ongoing struggle for liberty, humanity, and equality. There is music, film, performances, workshops, a Chartist Convention with historical and academic talks, a radical book fair, and… A Torchlit Procession Through The Streets.

And so I went to Newport in November, 185 years after the Chartists marched into town, and it was glorious. On the Saturday evening, following music, fire and speeches in Belle Vue Park, a momentary stillness and quiet witnessed the lighting of the first torches, and, as the flame was passed on, a 2,000 strong procession began to wind around the serpentine paths, pouring out into the streets and down Stow Hill with torches blazing, to the Westgate where more speeches and music culminated in an exuberant, joyful rendering of the Welsh National anthem. The people of Newport did their Chartist ancestors proud.

Two days later, on the anniversary of the original march, primary school children paraded around the town with their hand made Chartist banners, and in the evening a ceremony was held in St. Woolos churchyard where a plaque honours the ten Chartists buried there. Again, there were speeches and readings, in Welsh and English, before everyone laid a flower on the memorial. For those of us unfamiliar with the tradition, the organisers, with the gracious and generous spirit of inclusivity which epitomized the celebrations, had brought extra red roses.

What Happened to the Chartists after the Newport Rising?

Two more Chartist petitions were presented to Parliament. In 1842 a petition with over three million signatures was again rejected by Parliament. There were riots, strikes, and arrests. In 1848 a mass meeting of Chartists was held on Kennington Common in London, but the government prohibited the planned procession to Parliament to present a third petition. Fearful of demonstrators being killed and wounded if soldiers opened fire, O’Connor cancelled the procession; he and other Chartist leaders walked alone with the petition. This third petition was also rejected.

But the Chartists had sown the seeds of change and by 1918 five of the Charter’s demands had been enabled. The Reform Act of 1867 extended the vote to some working men; the secret ballot was introduced in 1872; payment of MPs came in 1911; and full manhood suffrage at twenty-one, plus a vote for women over thirty and subject to a property qualification, was achieved in 1918.

The three leaders who had been transported from Newport were pardoned in 1856. William Jones remained in Australia where he worked as a watchmaker. Zephaniah Williams remained in Tasmania where he mined coal. John Frost returned from Tasmania but went to live in Stapleton in Bristol where his wife and children had moved. He continued to publish articles about reform until his death in 1877 at the age of ninety-three.

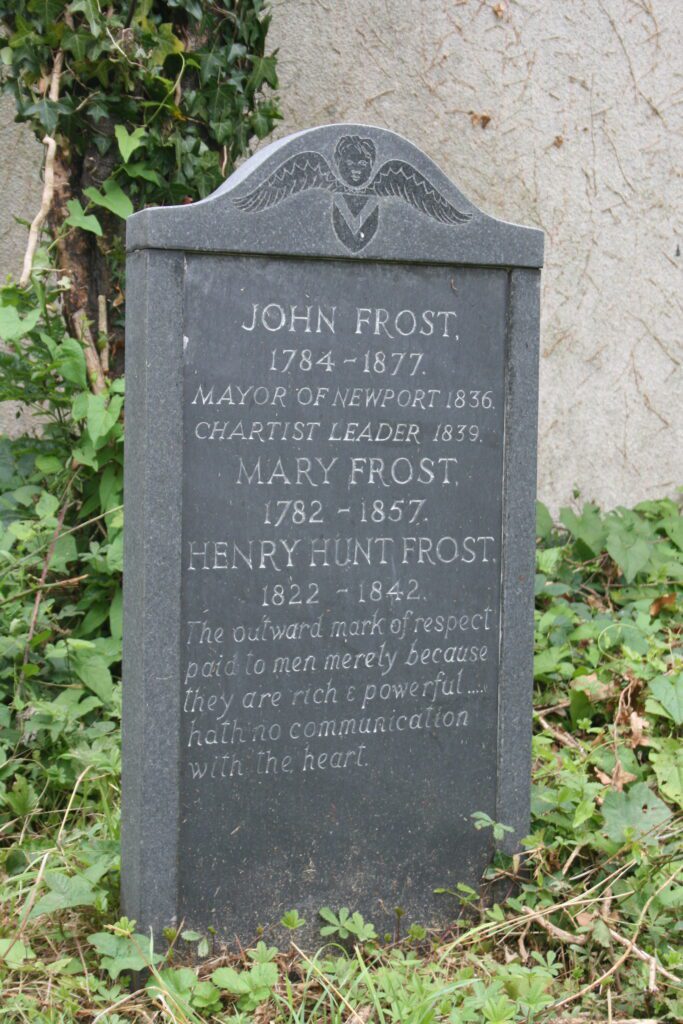

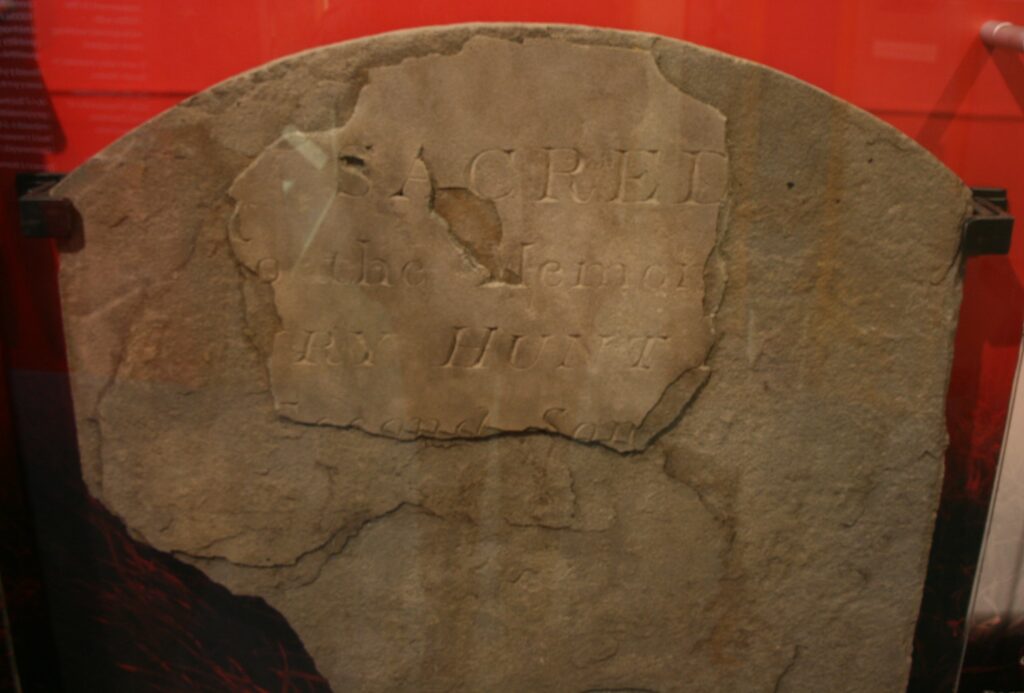

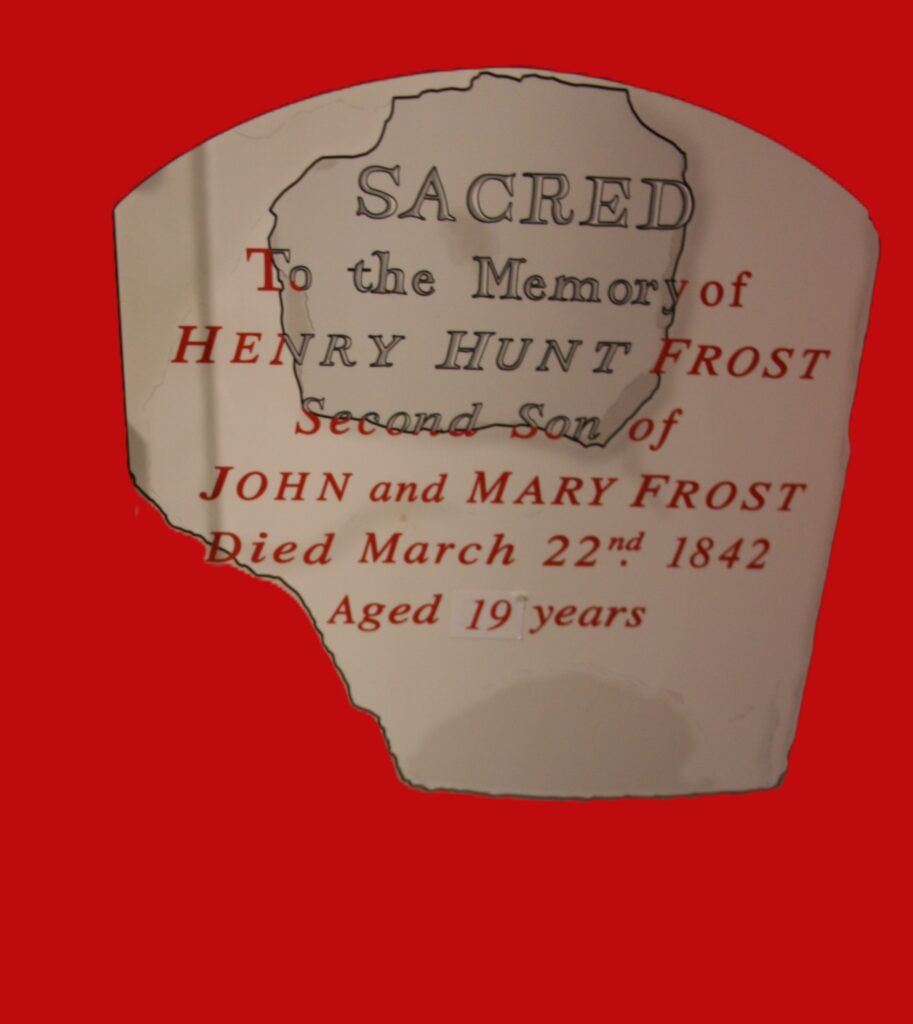

In the 1980s Newport historian Richard Frame learned from Frost’s will that he had requested to be buried in the grave where his son, who had died in 1842, lay in the churchyard of Holy Trinity, Horfield, Bristol. Frost had buried his wife, who died only a year after his return, in the same grave. Frame located a badly weathered and partially buried stone bearing the name of Frost’s son, Henry Holman Frost. Newport Council paid for a new headstone of Welsh slate with a granite surround. It bears a quotation taken from a letter which Frost wrote to Lord Tredegar;

“The outward mark of respect

paid to men merely because

they are rich and powerful…

hath no communication

with the heart”

The original headstone is in Newport museum along with other artefacts from the Newport Rising.

And in Newport now?

The Newport Rising Hub is open at 170 Commercial Street, Tuesday-Saturday 10am -4pm

There you will find an exhibition of radical history, leaflets on the Chartist trail, books and other Chartist merchandise, and details of more events in Newport.