When I was young I cherished a secret dream of becoming a civil engineer. Secret, because I knew, that with only modest ability in mathematics and no talent at all for drawing, this was clearly not where my future lay. But I longed to build bridges, I could imagine nothing more satisfying than being able to create those solid constructions which hang, as if by magic, in the air. Periodically some prosaic soul tries to explain to me the finer points of compression and tensile forces, torsion and shear, the importance of abutments and piers. But I prefer the enchantment of the unknown, the romance of the little understood; I am bewitched by the illusion of graceful weightlessness.

And no bridges hold a greater place in my affections than the hardworking Victorian bridges strung out across the Thames in London, each one with its own stories, myths, and idiosyncrasies.

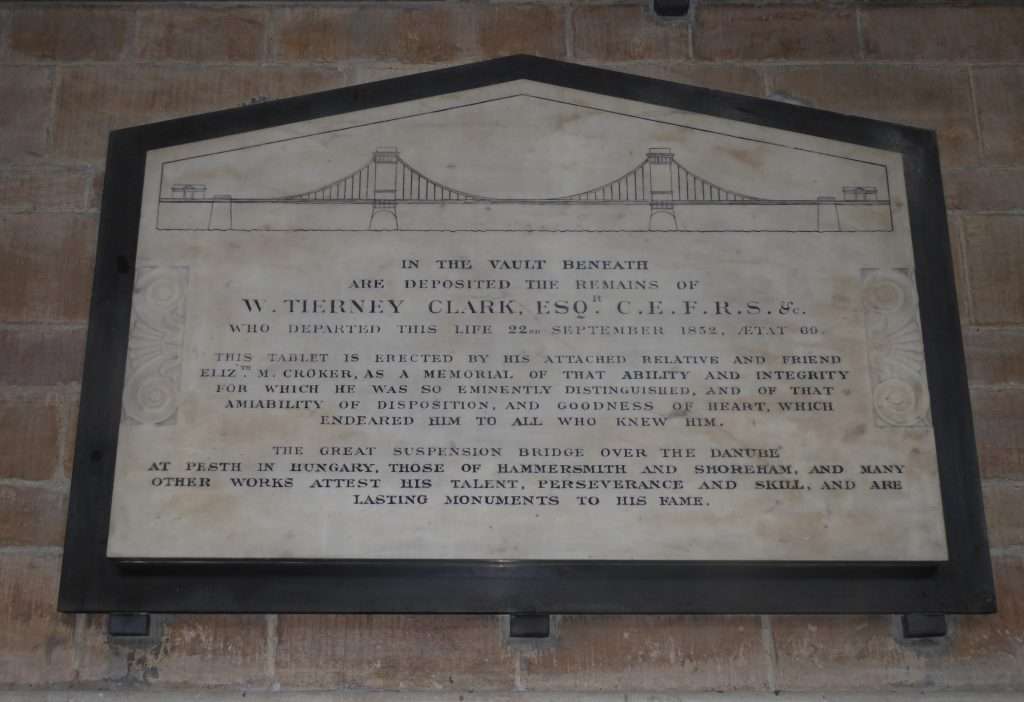

In West London in 1872 William Tierney Clarke designed one of the world’s first suspension bridges spanning the river between Hammersmith on the north bank and Barnes on the south. After a boat collided with it in 1884, Bazalgette rebuilt it in cast iron, with large chains supporting its roads and walkways, using Tierney Clarke’s original pier foundations. Urban myth has it that Harrods funded the magnificent dark green and gold paintwork of Hammersmith Bridge to match their nearby furniture depository and their Knightsbridge store. It could have provided subtle and splendid advertising, but the truth is that Bazalgette chose the colours before either of the Harrods buildings were completed.

The Albert Bridge is a pure sugar plum in pink, blue and green. Illuminated by 4,000 bulbs at night, this ethereal, highly ornamented, and richly decorated bridge stretches between Chelsea and Battersea. Once known as the “Trembling Lady” because of a tendency for its fragile structure to vibrate when subject to excessive traffic and immoderate footfall, it still carries signs at its entrances warning troops to brake step when they cross. In 1973 a proposal in The Architectural Review floated the idea of converting the bridge into a landscaped public park with a pedestrianised footpath across the river. This scheme had the backing of no lesser luminaries than John Betjeman, Sybil Thorndike, Laurie Lee, and Robert Graves, all of whom just happened to live nearby. Successful opposition from the RAC saw their campaign fronted by the unlikely figure of Diana Dors.

Lambeth’s five-span steel arches and the seven-arch cast iron structure of Westminster Bridge with its gothic detailing by Charles Barry, sport red and green paint respectively, reflecting their positions at the southern and northern ends of the Houses of Parliament where the Lords sit on red leather benches and the Commons on green. The stone pinecones surmounting the obelisks at either end of Lambeth Bridge are sometimes mistaken for pineapples, leading to fallacious claims that they were placed in tribute to Lambeth resident John Tradescant who grew the first pineapple in Britain.

More than a century after these Victorian bridges were built, the same oscillations that hounded the Albert Bridge caused the Millennium Bridge, less romantically designated “the Wobbly Bridge,” to close, only two days after it had opened, for modifications. This glorious steel “blade of light” designed jointly by the Arup Group, Foster and Partners, and Anthony Caro links Bankside and the City, connecting the Tate Modern to the glorious terminating vista of St. Paul’s. Walking across it is pure joy, but I rue the demise of the extra frisson which the oscillations provided.

I am surely not the only one to take special delight in Horace Jones’ Tower Bridge linking the Tower of London and Southwark. Completed in 1894, it is the most immediately recognisable of the London bridges with its towers and rising bascules opening to let tall boats pass from the Lower Pool of London to the Upper Pool. In 1952 a relief worker raised the southern bascule before the security guard had rung the warning bell and closed the gates to traffic. The driver of a no. 78 bus found himself on the rising bascule. With great presence of mind, he accelerated, and the bus leapt onto the northern bascule which had not yet begun to rise. He later explained that he had been a tank driver during the war and that since a tank would have had no trouble in jumping the gap he decided to see if a double decker bus could do the same. A delightful short Pathe film shows a representative of the City Corporation presenting the driver with a reward, £10 and a day off work, for his quick thinking and unruffled response.

(See towerbridge.org.uk/discover/history/bus-jump and scroll down).

Seeking to pay homage to all the bridge builders, I sought out Horace Jones as their representative, and I confess to a little disappointment on locating his rather bleak, austere grave in West Norwood Cemetery.

But Horace Jones’ spirit lies not in the graveyard but in the enchantment he left for us every time the bascules of Tower Bridge rise. And for as long as their preternatural structures hover weightless in space, all the bridge builders have fitting memorials.