Last week I watched Dramakarma’s production of Two Thousand Days at the Merlin Theatre. Dramakarma is a community-based project in Frome providing drama classes for young people and staging performances based on historical events in the town.

Two Thousand Days told the story of the evacuation of The Coopers’ Company’s School from Bow, in East London, to Frome in Somerset, where the school remained for the duration of World War Two.

On 3rd September 1939 Britain and France had declared war on Nazi Germany; two days earlier Operation Pied Piper had been instigated. This undertaking, named ironically, if not inappropriately, after the menacing German folk tale, aimed to remove schoolchildren, and mothers with infants, from urban locations, where there was a high risk of enemy bombing, to safer rural areas. During the first three days of the operation one and a half million people were moved, of whom 827,000 were school age children.

The government had decided to billet the evacuees in private homes rather than special camps. The hosts in reception areas were paid a weekly allowance but fined if they refused to take evacuees. The billeters, as they were known, were identified by the space available in their homes rather than by their suitability to care for children. Unsurprisingly, while some hosts were kind and welcoming, others were resentful. For some children, the experience was an adventure leaving them with fond memories of their surrogate parents with whom they retained contact. Others were miserable, homesick, and treated with indifference.

The Coopers’ Company’s School, founded in 1536, had remained in London even during the Great Plague, but on 1st September 1939 their pupils gathered at the school, each carrying one small suitcase, an overcoat, and a gas mask. Like all evacuees they marched to the local railway station and boarded trains to an unknown destination. Only after they had arrived was the school telegraphed and a notice pinned up telling parents where their children were.

Things did not always run smoothly, and the pupils, who were supposed to have been evacuated to Taunton, somehow found themselves in the Wiltshire hamlet of Ramsbury where the residents, expecting a small number of women and babies, were faced instead with over 380 schoolboys. The cots which the villagers had decorated with pink and blue ribbons were superfluous to requirements.

After three weeks, during which they were accommodated in barns in Ramsbury and surrounding villages, the school moved to the market town of Frome. Occupying buildings previously used by Frome Grammar School which had moved to new premises, The Coopers continued in Frome for 2000 days, until 19 July 1945.

Dramakarma adapted the memoirs of pupils,* and the effervescent cast of 13- 18-year-olds brought them to life. The memories were not always happy ones, and we witnessed the agony of children waiting in the community hall to be “picked” by the billeters, then facing callous treatment: locked out of their new “homes” during the daytime, and eating separate, inferior meals from their host families.

For most of the time however the mood, in line with the published reminiscences, was upbeat. Alongside their traditional curriculum the boys learned to repair shoes, they put on plays, and developed new skills as diverse as book binding and ballroom dancing. There may have been no gas, electricity or running water in some of their billets, but there were plentiful supplies of elderberry wine, and entertainment was to be had exploring the old quarry workings and, unknown to the schoolmasters and the billeters, midnight swims in the lake at Orchardleigh. They had close encounters with herds of bullocks on the country roads, sat on boxes playing chess on the frozen lake in the harsh January of 1940, and learned to wrap a brick which had been in the fire all day in a cloth bag for warmth in bed at night.

Above all they had the most extraordinary freedom, trespassing cheerfully on the neighbouring estates, and on their bikes exploring the surrounding towns of Bath, Warminster, and Wells. When the bombing was not bad the headmaster allowed them to cycle home to London, a distance of some hundred miles, during holidays. Leaving Frome one Good Friday three lads cycled through the night without lights in the blackout, returning the following Monday. The unmitigated euphoria vouchsafed only to inadequately supervised teenagers, free to roam with their mates, radiated from the stage, and everyone came away from the production smiling.

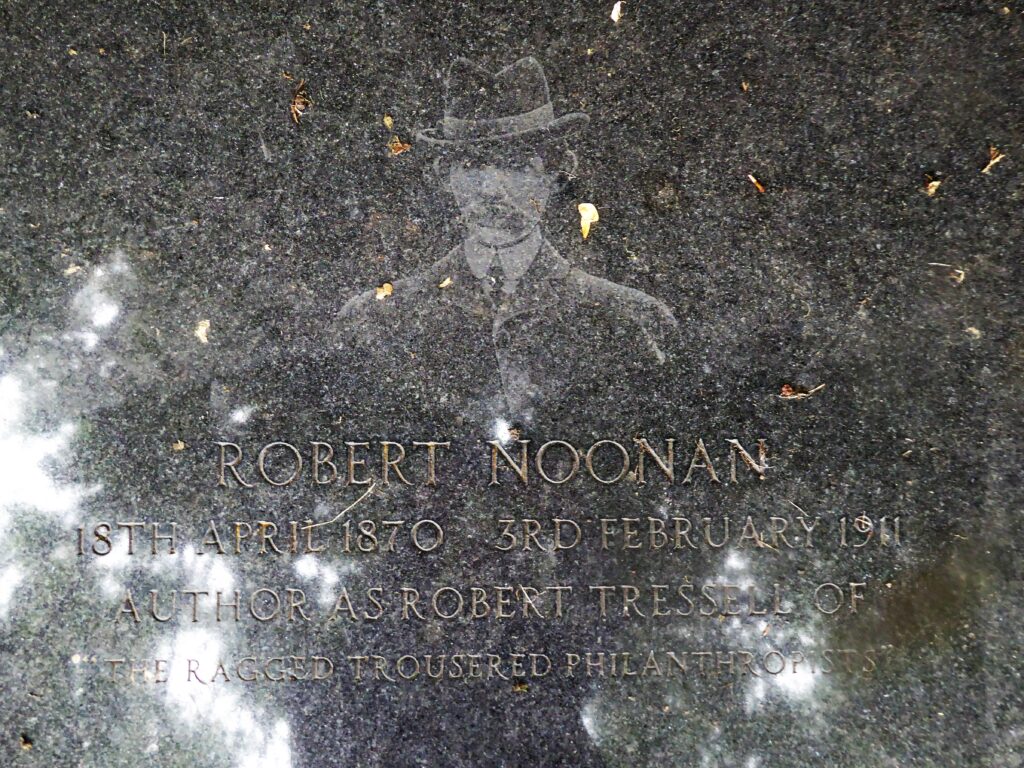

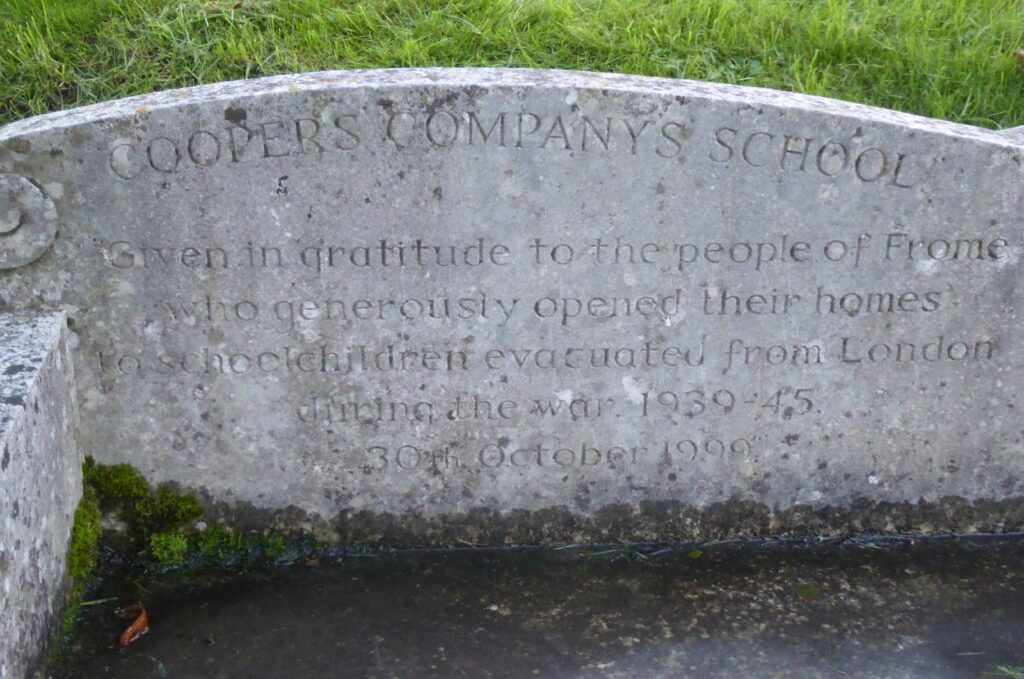

It is a measure of the affection with which they came to hold Frome that the evacuees continued to visit the town throughout their lives, holding reunions, looking up old friends and those who had welcomed them with kindness. In 1951 they donated two teak seats, set in St. John’s churchyard, to the town. When the the seats eventually fell victim of the weather,they replaced them in 1999 with a bench made of Portland stone.

Given in gratitude to the people of Frome

who generously opened their homes

to schoolchildren evacuated from London

during the war 1939-45

Twenty Old Boys and the ninety-year-old former school secretary were present at the dedication ceremony. Few of them remain now, but Richard Beer, who first arrived in Frome as a twelve year old evacuee, was guest of honour when Two Thousand Days was first performed as part of the Frome History Festival in May this year.

It isn’t a grave, but the bench serves the same purpose, remembering the boys who for 2000 days made Frome their home, and the townsfolk who welcomed them, a life time ago.

*The Coopers’ Company’s School in Frome 1939-45 edited by George S. Perry.