The church at Norton Saint Philip boasts a clock by Vulliamy and Frodsham dating from 1848. It is not the oldest church clock in Somerset, but it is one of the few still wound by hand. Twice a week clock winders winch up three weights in a pulley system and as they descend the clock strikes the hour, the half, and the quarters. Every sixth week we take our turn on the clock winding rota, climbing the narrow spiral staircase up the tower to a point where we look down on the bell ringers but up to those charged with care of the flagpole.

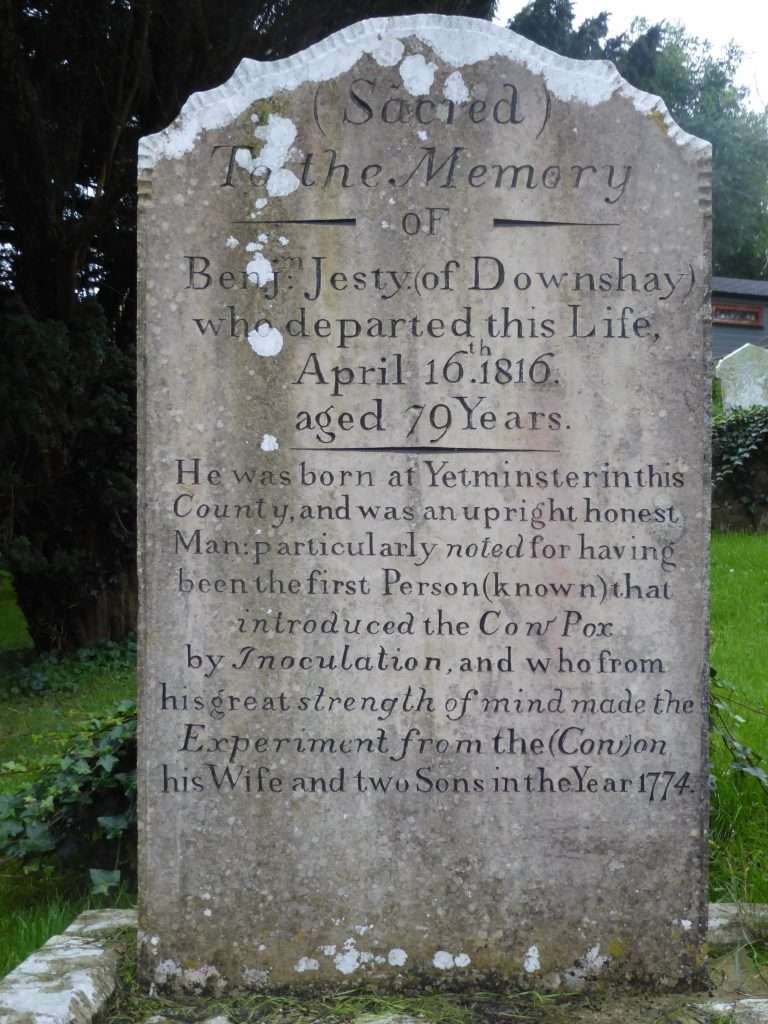

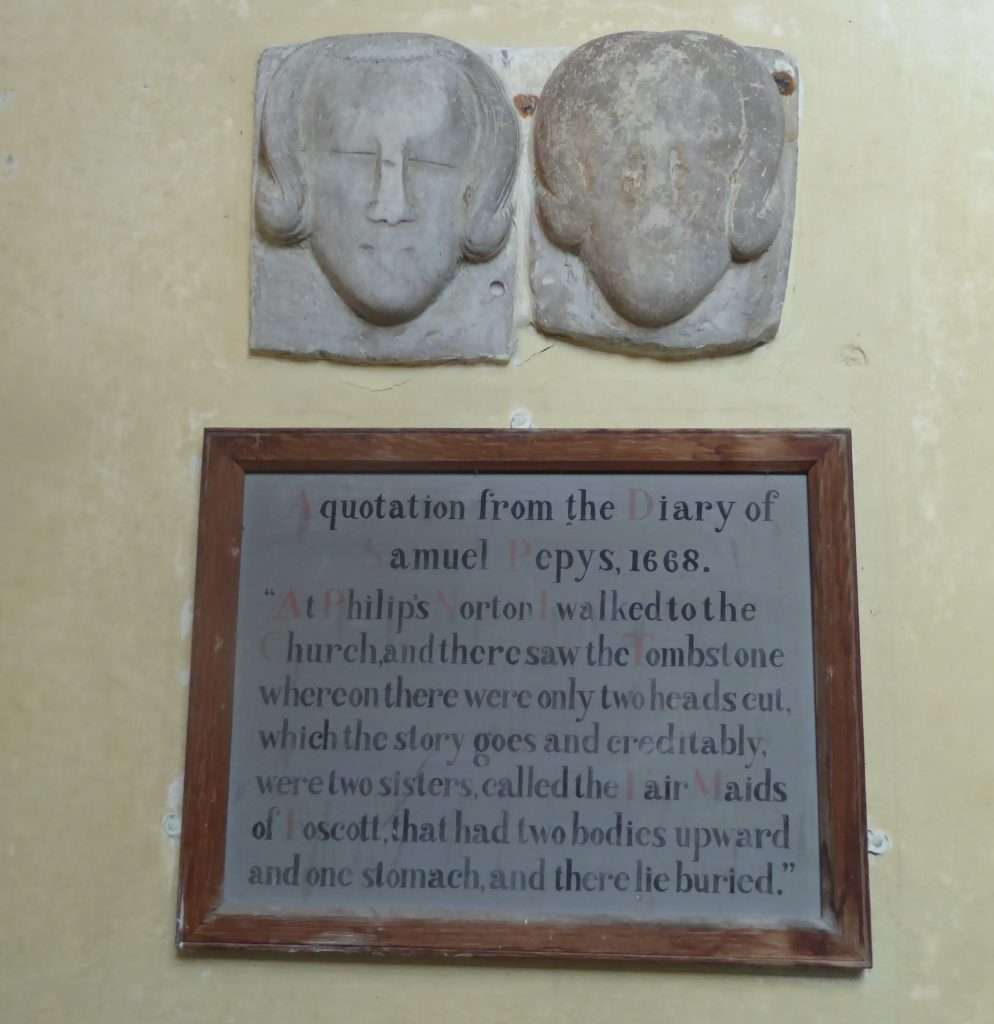

The base of the tower at the west end of the church is not its most attractive feature: here behind closed doors spare chairs are stacked, vases and watering cans jumble together, notice boards superfluous to current requirements lean drunkenly against the walls, plastic boxes spill electrical odds and ends, and what looks suspiciously like a hostess-trolley lurks in one corner. It has in truth a desolate air, the few memorials lining the walls have known better times and they look down disconsolately on the dusty impedimenta. But these memorials are the survivors: they were moved from the floors of the nave, chancel, and aisles to the tower walls during Gilbert Scott’s reconstruction of the church in the 1840s, when others disappeared entirely. And high on the north wall are the sisters whom I always greet: two small female heads, crudely sculpted with flicked up hairdos reminiscent of Millicent Martin on TW3 in the mid-sixties, they are roughly attached to the wall.

They have no words of their own but beneath, in a shabby frame, a faded notice recalls a quotation from the diary of Samuel Pepys:

At Philip’s Norton I walked to the

Church, and there saw the Tombstone

whereon there were two heads cut,

which the story goes and creditably,

were two sisters, called the Fair Maids

of Foscott, that had two bodies upward

and one stomach and there lie buried.

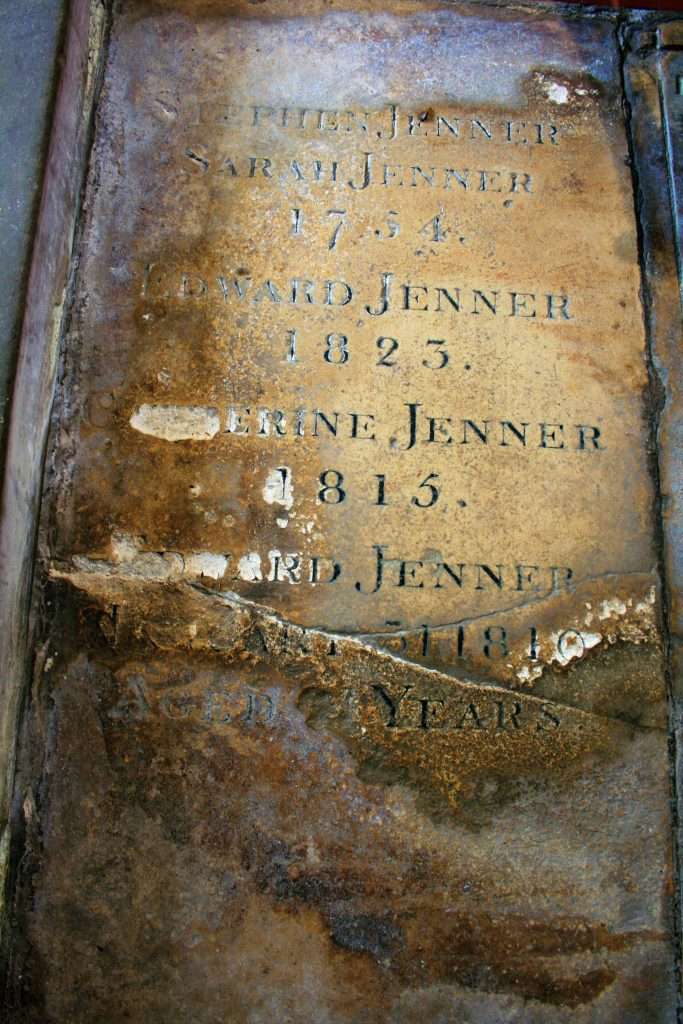

Pepys and his wife visited Philip’s Norton in June 1668. Foscott, now Foxcote, is a hamlet a few miles from Norton and when Pepys saw the tomb the effigy of the conjoined twins was cut in stone in the floor of the nave. Later the Somerset Historian John Collinson recorded in the third volume of his History and Antiquities of the County of Somerset published in 1791 that “In the floor of the nave…are the mutilated portraitures, in stone, of two females, close to each other, and called, by the inhabitants, the Fair Maids of Foscott, or Fosstoke, a neighbouring hamlet, now depopulated. There is a tradition that the persons they represented were twins, whose bodies were at their birth conjoined together” and, he adds gruesomely, “that they arrived at a state of maturity; and that one of them dying the survivor was compelled to drag about her lifeless companion, till death released her of the horrid burden.” Today nothing remains of the tombstone save for the heads, the rest probably destroyed during Gilbert Scott’s restoration.

Pepys also noted that while in the church he “there saw a very ancient tomb of some Knight Templar, I think.” The latter still lies in the south aisle but is now identified as a lawyer of the fifteenth century wearing a barrister’s gown. More loved than the Maids he is often in receipt of tribute, near disappearing beneath greenery at Christmas and well supplied with apples at harvest.

Just a year after this visit Pepys himself had cause to erect a memorial: his wife, Elisabeth, died and he had a marble bust of her installed at Saint Olave’s in the City of London where he was a regular worshipper calling it “our own church,” and which was later described by Betjeman as “a country church in the world of Seething Lane.” Elisabeth’s bust was positioned on the north wall of the sanctuary so that Pepys could see her from his pew in the gallery, and in 1703 he was buried next to her in the nave. His own memorial on the wall of the south aisle faces hers, and from their elevated positions they receive their many admirers.

Not so the Fair Maids, a little lonely these days in their tower with only the clock winders, flower arrangers, bell ringers, and flag hoisters passing busily beneath them as they go about their business. So, if you are in Somerset, follow Pepys’ example: come to this country church in Norton Saint Philip and visit my friends the Maids, say hello to the lawyer too, and listen to the hand wound clock striking the quarters.