We were dismayed when we heard that for our teaching practice term we were to be scattered all over the country. During our first term we had enjoyed the rarefied atmosphere of Cambridge: observing in the Village Colleges; reading children’s literature; watching educational films; putting together themed multimedia presentations; filming each other microteaching – Chinese cookery, yoga, origami; mulling over our teaching practice wardrobes; and discussing “discipline” in an entirely theoretical manner. The Cambridge Village Colleges were not however, our supervisor informed us, representative of the range of abilities or the standards of behaviour which we might expect to encounter in the real world, and into that world we were now to be dispersed.

And so, I found myself at the wildly inappropriately named Heartsease Comprehensive School in Norwich. This is a little unfair, for Heartsease was a good school, despite its unwieldy size and disadvantaged catchment area. Indeed, at the time of my arrival it was shaking off an earlier reputation as a sink school and experiencing steady improvements. But it takes time to leave behind a problem school label, and I was conscious of benefitting from this, looking smugly nonchalant when fellow students reported rumours that mine was a difficult school and wondered sympathetically how I was coping.

My passage was eased further by the exceptional teachers in the English Department who gave generously of their time and expertise. In handing over the classes which they had carefully nurtured to my inexpert care, they were risking having to make up lost ground in the future and meanwhile putting themselves in the front line for “cover.” This frequently meant periods with the most difficult classes in the school when less scrupulous staff in other departments “went sick,” an event which happened with odd frequency on Friday afternoons.

Not only did they lend me their pupils, but it was also clear that they had briefed them to act with consideration towards The Student. For student teachers are fair game to bored teenagers, and with no malice intended they can easily derail painstakingly wrought lesson plans and reduce their captives to jabbering, drivelling incoherence. But my charges were clearly honour- bound to respect the moral strictures of their real teachers, so that even my least successful efforts met with little more than an exchange of indulgent smiles, raised eyebrows and the occasional, “O, Miss,” when my lesson floundered.

So, given a free hand, I embarked with confidence one morning on a comparative analysis of Wilfred Owen’s Strange Meeting and Henry Newbolt’s Vitai Lampada, ostensibly to illustrate the difference between good and bad poetry. There was a hidden agenda, for I was hoping that Wilfred Owen’s heart-rending condemnation of war would turn them against the jingoism exemplified by Newbolt’s poem.

But to a person my pupils embraced Vitai Lampada: they liked the tempo; they liked the rhythm; they liked the rhymes; they liked the imagery; they liked the emotion, the immediacy, and the vivid metaphor. They liked the sentiments of honour, nobility and selflessness. Useless for me to argue that the poem was maudlin, mawkish, manipulative, banal, cloying, and cliché ridden, that it was disingenuous to compare war with a cricket match, that the cheery tempo they liked so much was inappropriate for a poem about war. Losing sight of the question of literary merit, writ large in my lesson plan, I focused on the values espoused in the poem: hierarchy, unquestioning respect for authority, blind obedience to orders, Imperialism, a public-school ethos, and (this last in a blatant attempt to win over the girls) a toxic masculine culture. My pupils, normally loud in their condemnation of all these attitudes, were unmoved; they liked the poem – a lot.

Strange Meeting on the other hand met with a stony response: it was gloomy; miserable; did not rhyme properly. I struggled in vain to explain pararhyme, to suggest that Owen used it to promote unease, a bleak atmosphere, melancholy. My pupils were unimpressed. I tried them on realism, on poignancy, on irony, the dead soldier, who could have been a friend, killed by the protagonist. They were impervious to my arguments. Abandoning any pretence that we were debating the quality of the writing I focused on the message: war was arbitrary, futile, wasteful, organised brutality, the battlefield a dehumanising hell of hopelessness and horror. My charges nodded, “Yes, it is a really miserable poem.” But, I continued, the poem also points to the possibilities of choice, forgiveness, shared humanity, reconciliation. “Preferred the other one.”

I met with wry smiles in the staff room when I reported ruefully on the double failure of both my overt and my covert lesson plans.

Soon after qualifying I abandoned the teaching of English Literature, turning instead to delivering Politics classes. But I remember with gratitude the support of the English staff at Heartsease in the Easter term of 1980 and with amused respect the determination with which my pupils held to their own opinions.

And if I still have no doubt that Vitai Lampada is a deeply flawed poem, I have nonetheless visited Henry Newbolt’s grave in atonement for my attempt to use his poem for my own political agenda. The grave lies at the heart of the Orchardleigh Estate which was owned by the Duckworth family of publishers into which Newbolt married. When I first moved to Somerset it was a romantic lost domain, the grounds gloriously overgrown and the empty Victorian house bewitchingly mysterious. Today developers have cleared the parkland to accommodate a golf course, and revamped the house as a “Fairy-tale Wedding Venue” – three-day packages from £8,699. But the tiny thirteenth century church of St. Mary the Virgin remains untouched. It sits on a lake, protected by trees, and reached via a decorative iron foot bridge across a moat. Newbolt lies in the churchyard, near the edge of the lake under a small, worn, flat stone which describes him tersely as Henry Newbolt, Poet. His view of the lake has been somewhat obscured in recent times by the arrival of more Duckworths with grander stones, but it’s a charming, peaceful spot, with ducklings scuttling across the lake in springtime… and not a jammed Gatling in sight.

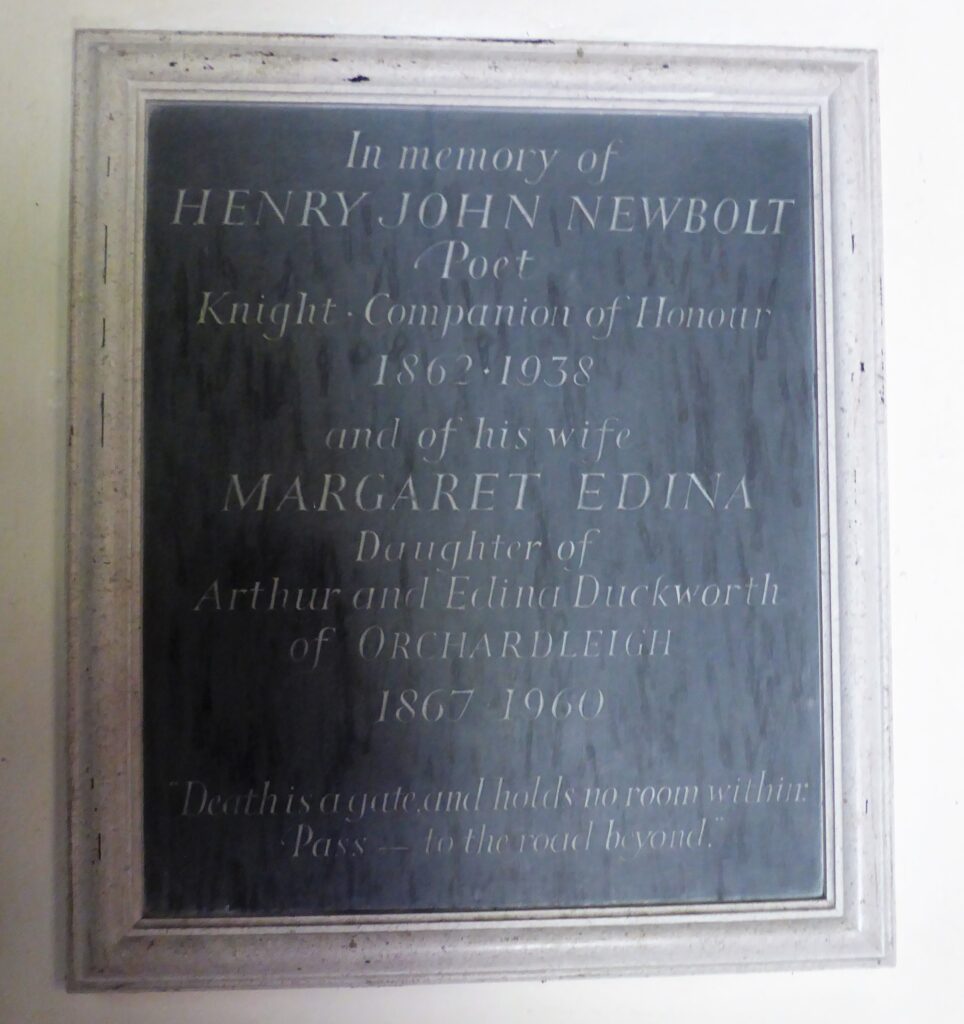

A memorial in the church bears a quotation from his own elegy, Mors Janua:

Death is a gate, and holds no room within:

Pass- to the road beyond.