A year on from the first Covid lockdown I turned to Daniel Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year to compare notes. His plague year was very much like ours: the first signs in Holland and rumours regarding the possible origins in Italy or the Levant, mirrored our own experiences watching Italy and Wuhan. The gradual spread from St. Giles and the West End to Cripplegate, Clerkenwell, and the City reflected our monitoring of Covid hotspots. The flight of the court and the well-heeled to their second homes was familiar; likewise, the first deaths and the sudden desolation in the streets with shops closed, Inns of Court shut up, theatres, alehouses, and diners all dark. Attempts to control wandering beggars resembled our own government’s sudden concern to house the homeless. The sick were either sequestered and died apart from their families or whole households were shut up in their homes, as happened in our hospitals and care homes. When Defoe bemoaned the lack of enough “pest houses” he might have been speaking of our own shortage of Covid wards leading to the construction of the Nightingale hospitals. Quack medicines appeared, just as hydroxychloroquine and the possibility of injecting bleach into our veins to wash out our lungs found favour in certain quarters in the twenty first century. Defoe recorded people moving to live on boats in the Thames or to camp in Epping Forest, and similarly at the height of Covid caravans and camper vans occupied green sites, sometimes received sympathetically by locals, at other times not. During the plague year the government forbade movement to second homes once people were sick, but some went against the rules; no need to labour the parallels. Daily and weekly recording of illness and death rates confirmed that then as now, the poor, living in overcrowded conditions with inadequate ventilation and unable to avoid the breath of others, sickened more than the wealthy. It became apparent that asymptomatic people could carry the plague. There were disruptions to trade and the closure of ports. As the plague intensified people rushed to stockpile provisions and there were shortages; they soaked their money in vinegar there being no contactless cards to replace cash. The poorest in the community found themselves out of work, unable to purchase food or pay for their lodgings. Charity, like our foodbanks, stepped in to supplement the parish relief which like our universal credit proved inadequate. Servants were redeployed as nurses, sextons, gravediggers. In Defoe’s London burials took place before sunrise and after sunset and neighbours and friends could not attend church funerals; when people died in the streets their bodies were removed in deadcarts to mass graves. Similarly in our own times government regulations limited numbers of mourners requiring them to be socially distanced, and as morgues and mortuaries became overwhelmed in 2020 contract workers wearing hazmat suits dug mass graves on Hart Island off the Bronx in New York. When, at last, the death rate began to decline JPs issued certificates of health to permit travel anticipating our own vaccine passports. Then as people became careless the rate rose again. Plus ça change…

There were differences, not least the greater presence of religion in Defoe’s Britain: sects, fortune tellers, and astrologers flourished; Solomon Eagle stalked the streets, naked with a pan of burning charcoal on his head, calling on the populace to repent; though some clergy fled, others kept their churches open; and when the plague ended Defoe gave credit for the recovery to god. Conversely there was less respect for the medical profession and far from clapping for carers Defoe wrote of nurses finishing their patients off and stealing their goods. And while, notwithstanding some fear of interspecies transmission, pet ownership increased during lockdown, Defoe’s London witnessed the wholesale killing of cats and dogs.

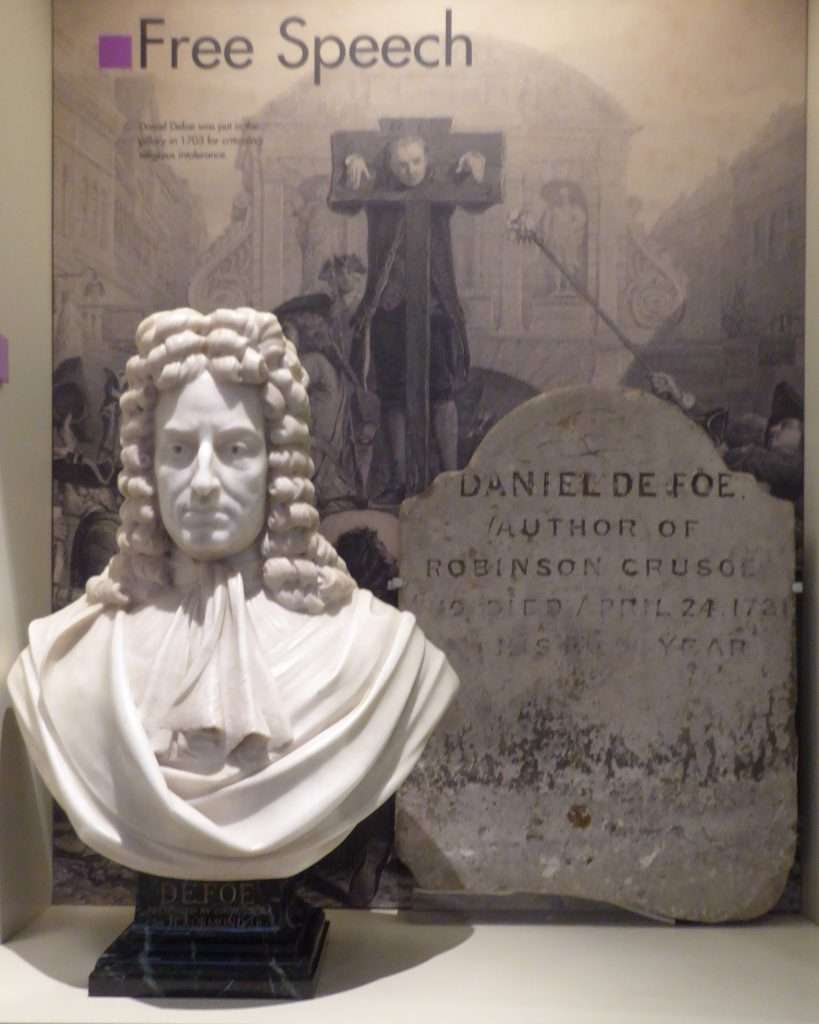

Defoe was only five years old in 1665 and the vivid “eyewitness account” which he recorded originated with his uncle Henry Foe, supplemented by Defoe’s own meticulous research. A man of many talents – merchant, spy, novelist, poet, political pamphleteer, and activist – Defoe’s life was a rollercoaster of excitement, achievements, and disasters. In 1685 he participated in the Monmouth rebellion against James II but escaped retribution in the Bloody Assizes, and when William III came to power became a secret agent in the pay of the latter. His poem The True Born Englishman defended William against racial prejudice, reminding xenophobic readers that they were all descended from immigrants. William’s death and the succession of Queen Anne led to the persecution of nonconformists and Defoe’s arrest in 1703 for pamphleteering, political activity and producing satires directed against high church Tories. Prior to his removal to Newgate, he was placed in the pillory for three days but his poem Hymn to the Pillory putatively resulted in the pillory being garlanded, flowers rather than rubbish thrown at him, and his poem sold in the streets. With the death of Queen Anne and the fall of the Tories he was able to resume work for the Whigs. Over five hundred works have been attributed to Defoe: away from the world of politics, these include Robinson Crusoe, Moll Flanders, A Tour through the Whole Island of Great Britain and of course A Journal of the Plague Year. No stranger to the debtor’s prison during his life he died, as he had often lived, in debt.

Defoe was buried in the Non-Conformist Cemetery at Bunhill but the original stone which marked his grave was struck by lightning and the headstone broken in 1857. James Clarke, the editor of Christian World, a children’s newspaper, encouraged his readers to donate 6d. each for a new memorial, setting up two rival subscription lists, one for girls and one for boys. An obelisk, raised in 1870 bore the inscription:

THIS MONUMENT IS THE RESULT OF AN APPEAL

IN THE CHRISTIAN WORLD NEWSPAPER

TO THE BOYS AND GIRLS OF ENGLAND FOR FUNDS

TO PLACE A SUITABLE MEMORIAL UPON THE GRAVE

OF

DANIEL DE-FOE

IT REPRESENTS THE UNITED CONTRIBUTIONS

OF SEVENTEEN HUNDRED PERSONS.

Samuel Horner, a stonemason from Bournemouth, erected the obelisk and took the original stone home with him, selling it as part of a general load from his yard. It became part of the paving of the kitchen floor at Bishopstoke Manor Farm until the farm manager, Frederick Stiles King, moving to a new house at 56 Portswood Road in 1883, took the stone with him, where it remained in his front garden for over 60 years. Charles Davey acquired it in 1945 and thirteen years later gave it to Stoke Newington library. There it lived in a glass case in the entrance lobby, an appropriate final resting place as Defoe had lived in Stoke Newington from the age of fourteen while he attended the Dissenting Academy under Charles Morton at Newington Green. But when I arrived at the library in search of the stone there was no sign of it. Happily, the librarian knew of its whereabouts: having been vandalised several times it had been moved to more secure premises in the delightful local history museum in Hackney where, beside a bust of Defoe and backed by a wall display of the famous pillory, it keeps company with other Hackney radicals, revolutionaries, and immigrants, not to mention a Saxon longboat and a complete reconstruction of a pie and mash shop.