Last week at an auction room in a small Wiltshire town a watch was sold for £1.175 million.

Henry Aldridge & Son in Devizes hold biannual sales of Titanic memorabilia and, at six times the expected figure, this represented the highest price ever paid for a single item.

The gold pocket watch was once the property of John Jacob Astor, but its value lay not in the gold nor in its ownership, but in the fact that it was found when Astor’s body was recovered from the Atlantic seven days after the sinking of the Titanic.

In April 1912 the RMS Titanic set out on its maiden voyage from Southampton to New York. Built in the Harland and Woolf shipyard in Belfast, and registered in Liverpool, the headquarters of the White Star Line, it was the largest and the most luxurious ship ever to sail. The opulence of the First-Class accommodation and public rooms was not extended to the hundreds of emigrants who travelled steerage, but even there the quality of the cabins was superior to the open dormitories common on most liners. The ship was described as unsinkable having sixteen watertight compartments on its underside which could be electronically closed if water entered them. Even if four of the compartments were flooded by a head on collision the liner was expected to remain afloat.

On the late evening of 14 April, the Titanic collided with an iceberg which damaged the ship’s plates below the waterline and five of the watertight compartments were breached. The ship began to founder and two hours and forty minutes later it sank. There would only have been enough lifeboats to accommodate one third of the passengers and crew had the ship held its full complement. As it was there were only places for half of them and in the disorganised evacuation the boats were launched barely half full. Of 2,240 people on board,1,517 people died from drowning or hypothermia.

The official inquiry into the disaster found that regulations on numbers of lifeboats that ships had to carry were out of date and inadequate; the captain had failed to heed ice warnings; the lifeboats had not been properly filled; the collision resulted from the ship steaming at too high a speed in a dangerous area. But it concluded that since all these were standard practice and not previously shown to be unsafe, the incident was an Act of God. New safety measures were recommended but no negligence was found.

The sinking of the Titanic has commanded extraordinary and enduring fascination. Immediately there were novels, poems, songs, art works, postcards, commemorative plates, and a silent film Saved from the Titanic starred the actress Dorothy Gibson who had in reality been one of the surviving passengers. Other badly flawed but high grossing films which followed in 1953 and 1997 served to increase the Titanic obsession.

The discovery of the wreck on the ocean bed in 1985 led to exhibitions of recovered artifacts and expeditions in submersibles for tourists to view the wreckage. One of those submersibles, Titan, itself imploded in 2023 killing everyone on board.

There are at least five Titanic museums and experiences in the USA, others in Canada, Ireland, and Britain. In South Africa, the businessman Sarel Gaus, and in Australia the billionaire Clive Palmer, abandoned grotesque plans to build full sized replicas of the Titanic when faced with prohibitive costs. In Sichuan in China a rusting hulk is all that remains of a similar project designed to be a floating hotel.

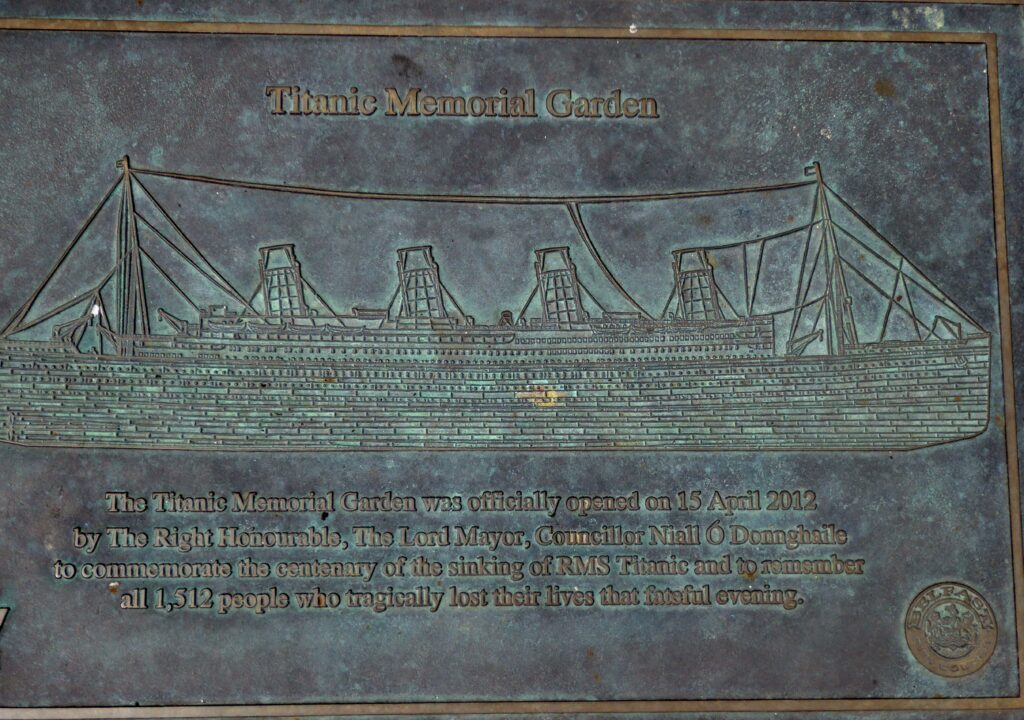

The centenary of the disaster in 2012 was commemorated with radio programmes, postage stamps and, with questionable taste, restaurants offering Titanic Themed Dining Experiences recreating the final dinner served in the first-class restaurant.

The Titanic Experience in Belfast, located on the site where the ship was built, also opened in 2012.

Whether spawned by nostalgia for an age of luxury, the wealth of social history provided by the extensive reportage and collected artefacts, or by a degree of schadenfreude in the face of arrogance and hubris, Titanic mania shows no sign of abating.

But what of the victims and survivors? Only three hundred and thirty-seven bodies were recovered. One hundred and nineteen, mainly third-class passengers and crew, were buried at sea, and a further one hundred and fifty in Halifax, Canada. Only fifty-nine bodies were claimed and repatriated.

Most of the lost crew came from Southampton where seven hundred red dots marked on a floor map of the city in the museum identify the addresses of those who died. None of their bodies were brought back because White Star wanted to charge freight fees which families could not afford. At Southampton Old Cemetery there are sixty graves with Titanic associations, but all the names were added retrospectively when widows or other family members were buried.

Similarly, Ernest Thomas Barker, a saloon steward, buried at sea, is named on a family grave in Highgate East.

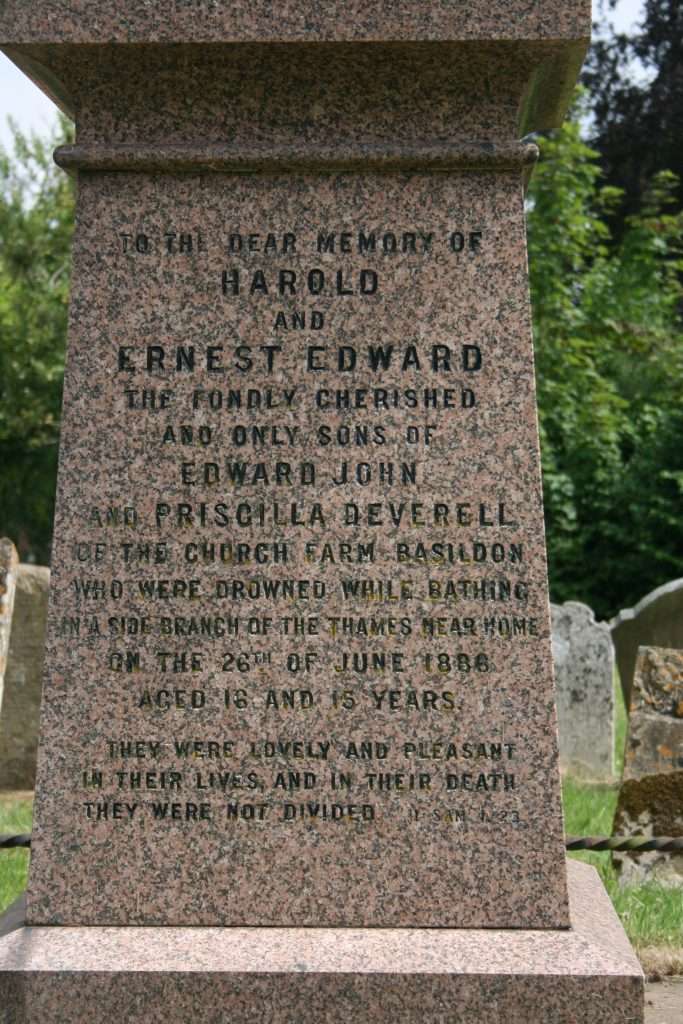

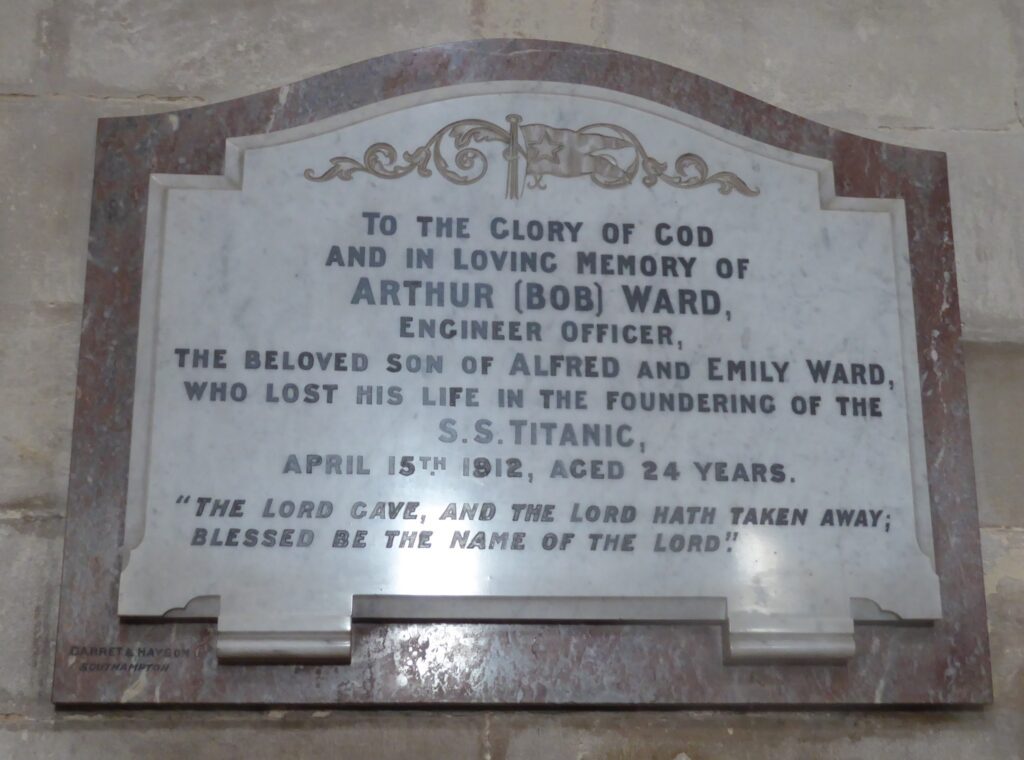

In Romsey Abbey, a memorial remembers Bob Ward, engineer.

In Belfast, a memorial outside the City Hall commemorates twenty-two men from Belfast who died in the disaster.

A memorial garden established around the sculpture at the centenary houses bronze plaques naming all the victims.

Liverpool has a handsome memorial to the ship’s engineers at the Pierhead, and in the Philharmonic Hall a plaque to the ship’s orchestra.

In Eastbourne in 1914 the opera singer Clara Butt unveiled a tablet opposite the bandstand on the seafront commemorating John Lesley Woodward, the cellist in the orchestra. Woodward, whose body was not recovered, had previously played at The Grand Hotel in Eastbourne.

St. Giles Hill Cemetery in Winchester houses the grave of William Arthur Lucas, a seaman who survived the sinking, served in the First World War, but shot himself in 1921 on a train from Leeds to Kings Cross. He died in the Royal Free Hospital, the coroner returning a verdict of suicide while insane. Also remembered on the stone is his brother-in-law Montague Vincent Mathias, another seaman who perished on the Titanic and whose body was never identified. Gertrude Mathias (nee Lucas) commissioned the stone for her brother and husband.

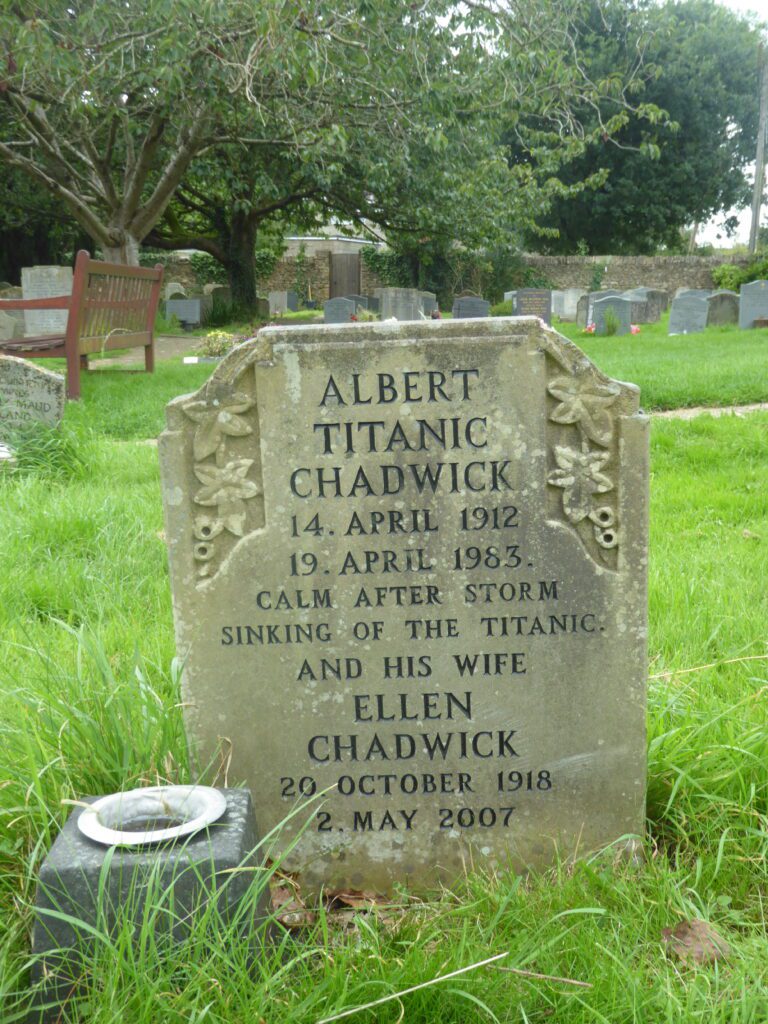

It is not uncommon to find graves where people are defined by their association with the Titanic, either as victims or less commonly survivors. But Albert Titanic Chadwick buried in Sherston, Wiltshire is neither. When I first saw his grave, I thought that he must have been born, and possibly christened, on the Titanic on the very day before it sank. But there were no Chadwicks on the ship, and the strange middle name remains a mystery. For all the bizarre souvenirs on sale in the aftermath of the disaster, it still seems extraordinary that anyone would name their child after such an event.

Two graves hold men who have been cast respectively as villain and hero of the maritime tragedy.

The chairman and managing director of the White Star Line, J. Bruce Ismay, was one of only 20% of the men on board who survived, but his reputation suffered. He was vilified in both the American and the British press for leaving the ship when there were still women and children on board. An inquiry into the sinking concluded that he had helped other passengers before leaving himself on the last lifeboat on the starboard side twenty minutes before the ship sank and he was exonerated from blame.

Ismay kept a low profile for the rest of his life but has a conspicuous grave in Putney Vale cemetery in London. The unusual design by Alfred Gerrard, is composed of three stones representing the prow, mast, and stern of a ship.

The upright stone representing the prow bears an inscription taken from the Epistle of James 3,4:

Behold also the ships, which though they be so great, and are driven of fierce winds,

yet are they turned about with a very small helm, whither so ever the governor listeth.

The chest tomb representing the mast bears scrimshaw like decoration with sailing ships and a compass.

On the top of the tomb is an extract from Psalm 107, verses 23-24:

They that go down to the sea in ships, and occupy their business in great waters,

These men see the works of the Lord, and his wonders in the deep.

A stone seat carved with plants and a verse by Elizabeth Barrett Browning represents the stern of the ship.

-The little birds sang East, the little birds sang West

And I smiled to think of God’s greatness flowed around our incompleteness,

Round our restlessness, his rest.

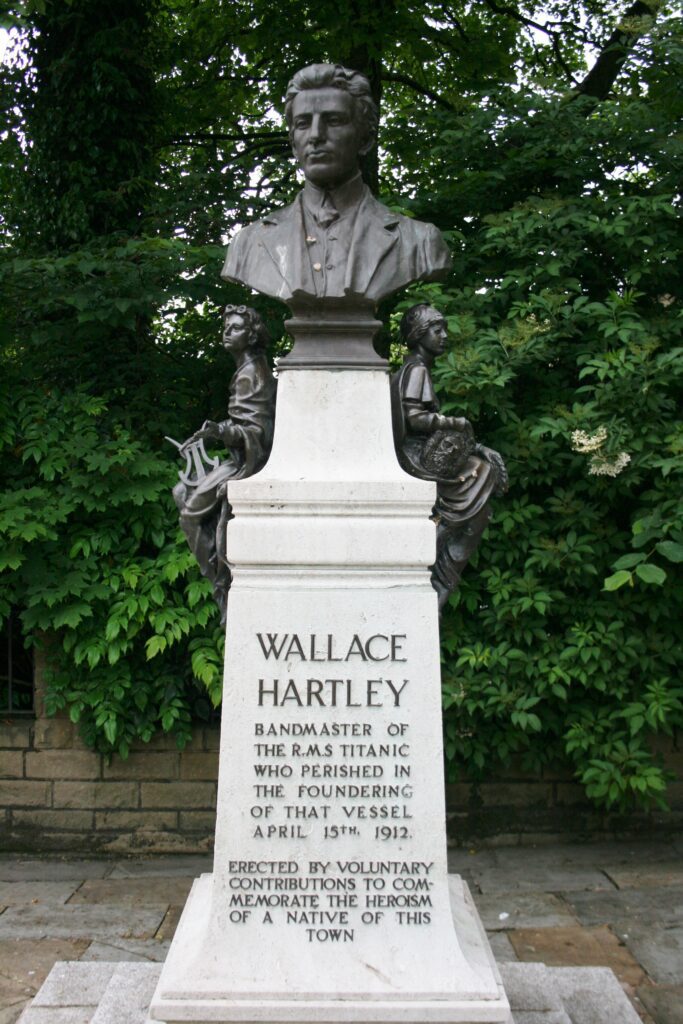

No controversy surrounds the memory of Wallace Hartley, and in his hometown of Colne in Lancashire, his reputation could not stand higher. He led the orchestra whose members stood on deck continuing to play amongst the chaos of the evacuation, attempting to maintain calm as the lifeboats were loaded. As the ship sank, survivor accounts describe them playing the hymn “Nearer, My God, To Thee.”

None of the eight band members survived, only three of their bodies were found. Hartley’s body was not found until two weeks after the sinking, by which time news of the quiet courage and dignity of band’s last performance had spread. Wallace Hartley was returned to England and his father took the body from Liverpool to Colne where 40,000 people lined the route of the funeral procession.

In the Keighley Road Cemetery above Colne on a grey, windswept hillside a broken column symbolises a young life cut short, and above a carved violin and the music score of Nearer my God to Thee, is a simple epitaph:

In the town centre a handsome memorial bust is flanked by a model of the Titanic planted around with blue and white flowers representing waves and icebergs.

There may not be any gold pocket watches on display in Colne, but they have a romantic local hero of whom they may be justly proud.