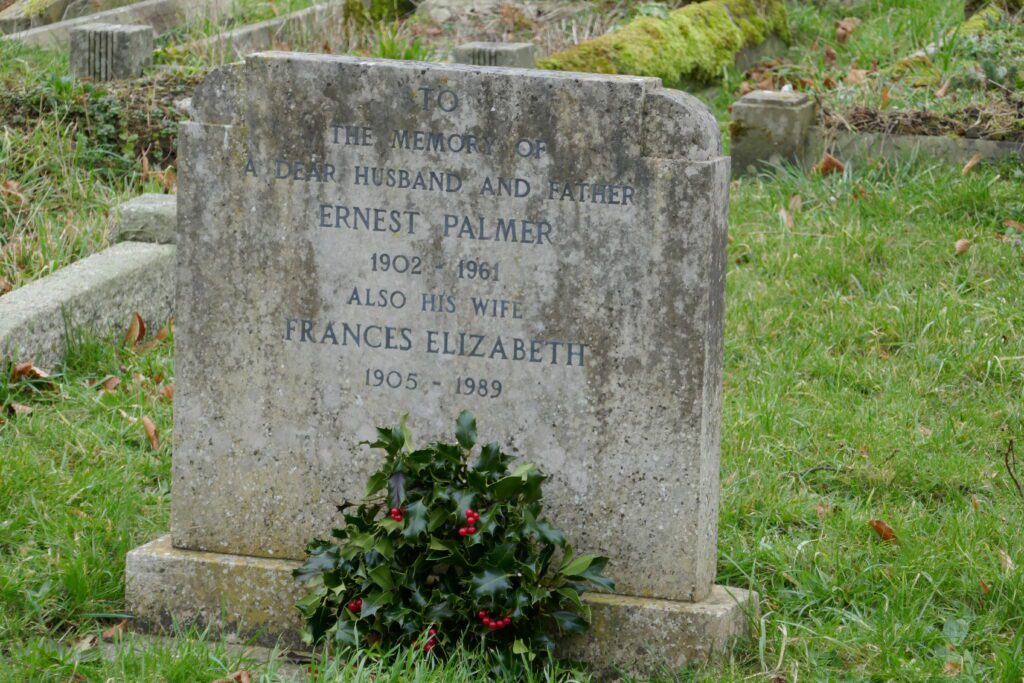

On my way to the village shop I take the path across the churchyard. The Christmas wreaths which adorned the graves last month are disappearing now, but the first snowdrops are pushing through the grass ready to encircle the stones.

Now that I have lived in the village for more than twenty years, I know a few of the inhabitants of the churchyard. They congregate beside the gate leading on to Church Mead. I pause wondering what Vivienne will think about the latest scheme to build more “executive housing” on the fields adjacent to the Mead, or what Den will have to say about the recent fly-tipping beside the brook in Wellow Lane.

I don’t need to solicit their answers, I can anticipate quite well the vehemence of their responses. I share their views: the Poundbury-pastiche housing with its pretentious porticos and faux bricked-up windows, ersatz facades, and sterile Stepford Wives ambience repels me too. Like them I seethe at the gratuitous dumping of rubbish in the woods and fields, on the roadside and in rivers.

At the same time, I smile at the memory of Den in his powerchair equipped with black sack and litter picker. The fridges and the mattresses may have eluded him, but with his dog running alongside the chair or hitching a lift, he waged a loud war on the beer bottles and fast-food wrappers tossed into the hedgerows by passing motorists.

A robin lands on the grave, cocks an eye at me, is unimpressed, and begins a furious excavation of the earth. Den was a gifted photographer, and I am reminded of his exquisite studies of birds and butterflies, fruits and flowers, and of his readiness to share his knowledge and talents with others.

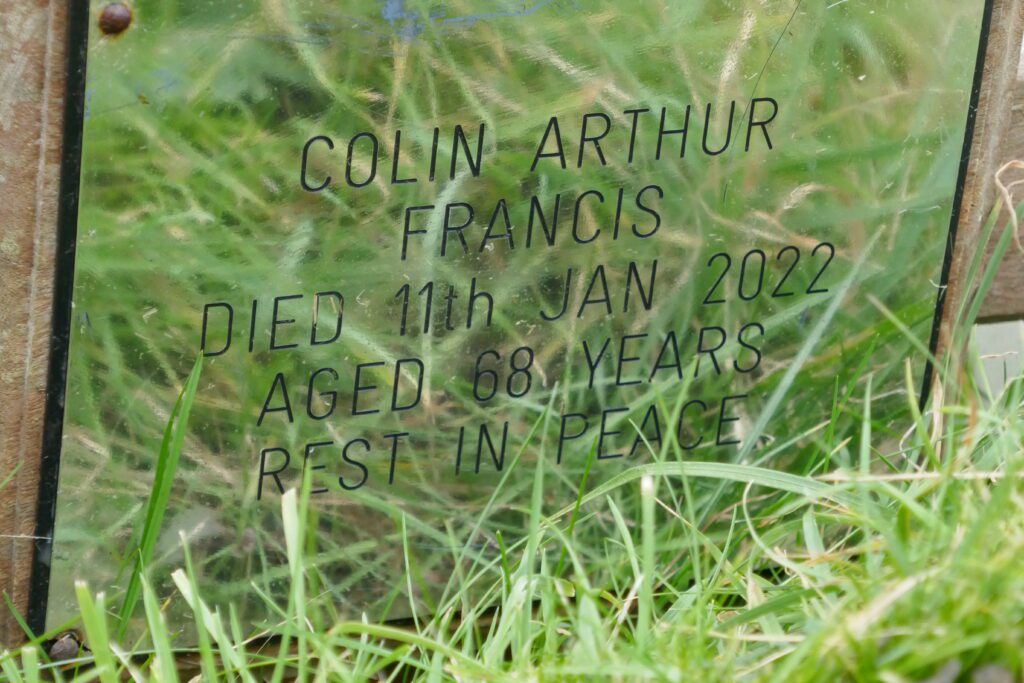

Mollified by these reflections, I turn to the grave of Colin Francis. Much loved in the village for his gentle charm and the warmth of his manner, Colin was a very special person.

Though he was quiet and modest, we were all familiar with the magnitude of his talent. For Norton Saint Philip is a village of dry-stone walls: the approach roads are lined by them, the fields and our gardens enclosed by them. Victims of erosion by frosts, unchecked ivy growth, trees planted too close leaning heavily into them dislodging stones and pushing them out of line, and the occasional rogue motorist, there is always a wall somewhere in the village in need of attention. And Colin, a stone mason, was also an expert dry stone waller.

In all seasons we encountered him stripping out the walls, removing ivy roots, sorting stones, and rebuilding. It was always slow work for dry stone walling is a separate technique from masonry, requiring skill and patience in choosing the right stones, setting them correctly, hearting each course with smaller stones, ensuring that each stone crosses a joint below it, and keeping the courses level.

Moreover, we would all hinder Colin in his work for none of us could resist to stop and chat, knowing our day would be enhanced by his always smiling good humour and his apparent pleasure at our interruptions.

Throughout one particularly bitter winter he worked his way along the length of the wall which lines the Bath Road into the village. He proved the most effective traffic calming scheme we have ever had as, commuting to and from work, we all slowed down to wave and check the day’s progress, or came to a complete halt the better to admire The Great Wall of Norton Saint Philip.

Colin was only sixty-eight when he died three years ago. Two hundred people packed into the village church to remember him. They did not all know each other but they shared a common sadness at the loss of this lovable man and his joyful approach to life.

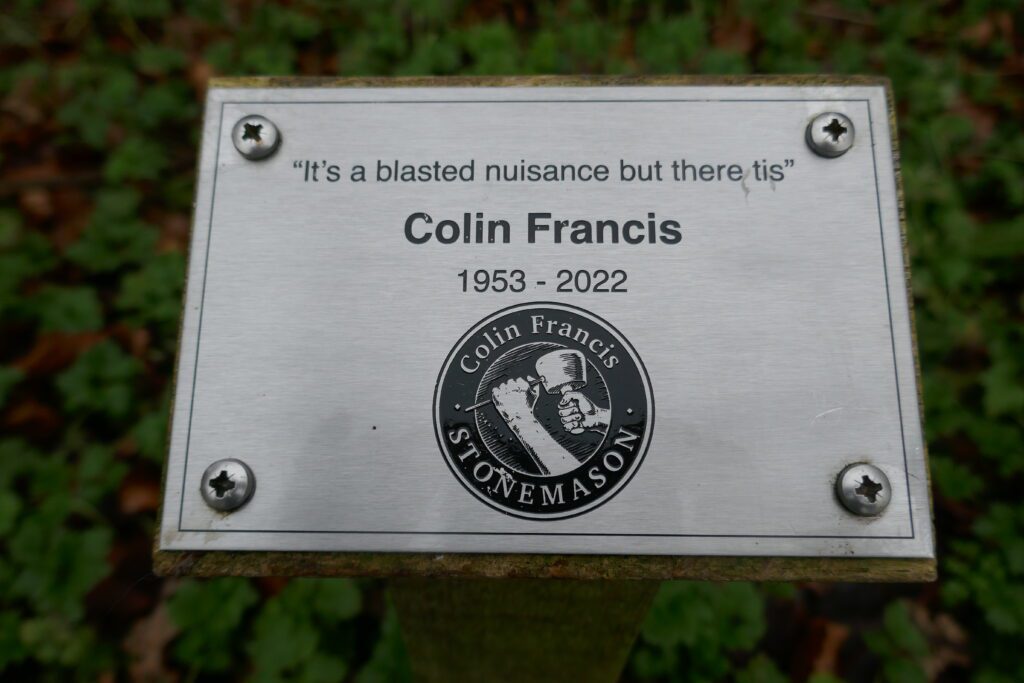

As well as the marker on his grave, a tree grows on The Mead in his memory. “It’s a blasted nuisance, but there tis,” reads the plaque beneath. This well remembered catchphrase was the closest he ever came to vexation.

But no one needs to locate either the grave or the tree to remember Colin, for like Christopher Wren,

Si monumentum requiris, cicumspire.

Colin is all around us, just out of sight behind the walls that enfold the village, his transistor radio playing softly as he plies his trade.