There are hourglasses, skulls, extinguished torches, broken columns, urns, anchors, arches, open books, angels, cherubs, lambs, clasped hands, myrtle and oak leaves, ivy, lilies, doves, swallows, trumpets, sheaves of wheat, fingers pointing upward or downward, rope circles, burning flames. The symbols commonly found on graves arouse little curiosity for their meanings are well known. Less obvious is the significance of a life-sized crouching lion atop a tomb. Yet I am familiar with three such lions, seemingly benign presences dozing above their occupants, casting the occasional contemptuous glance at the lesser memorials scattered beneath their eminence.

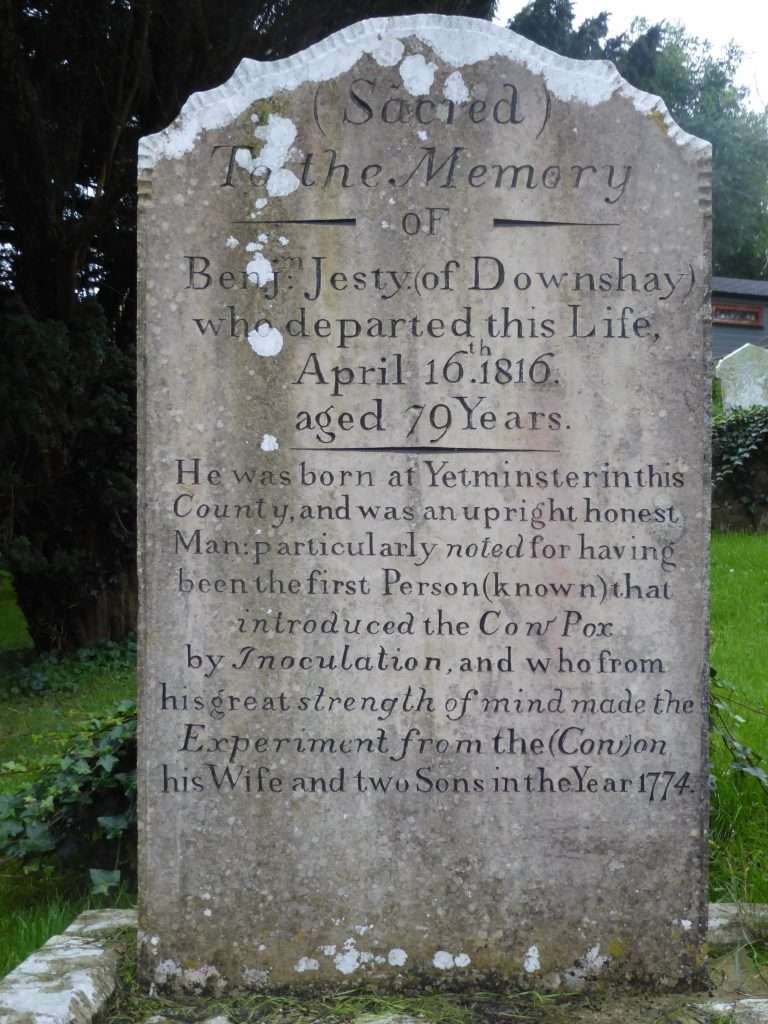

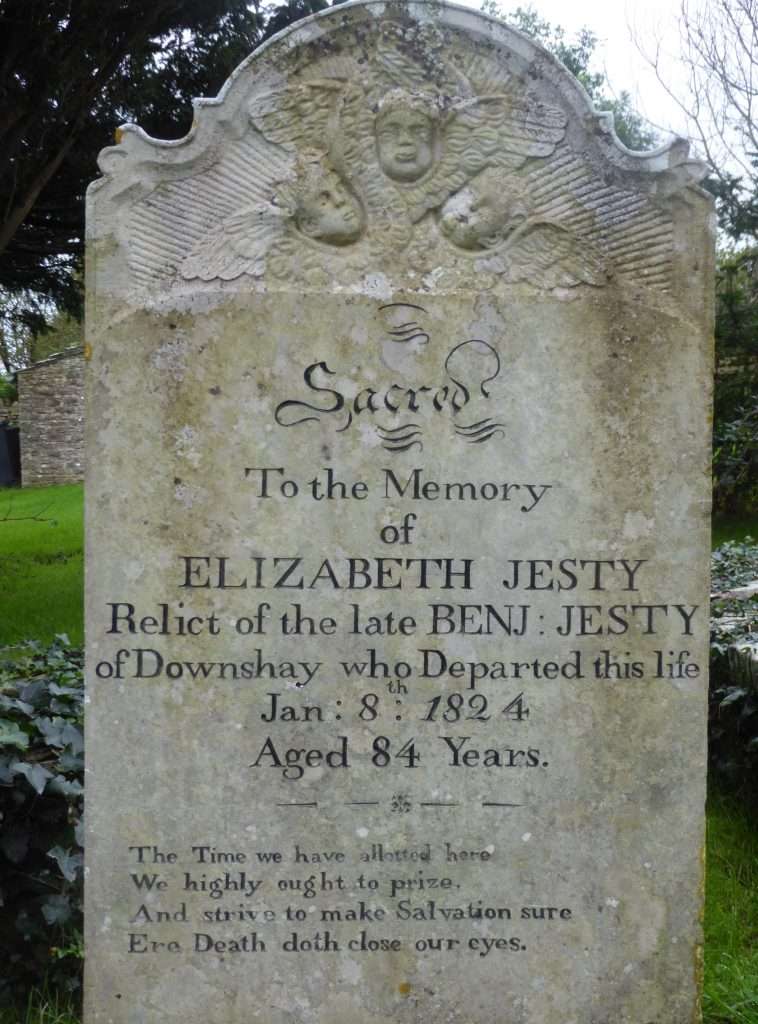

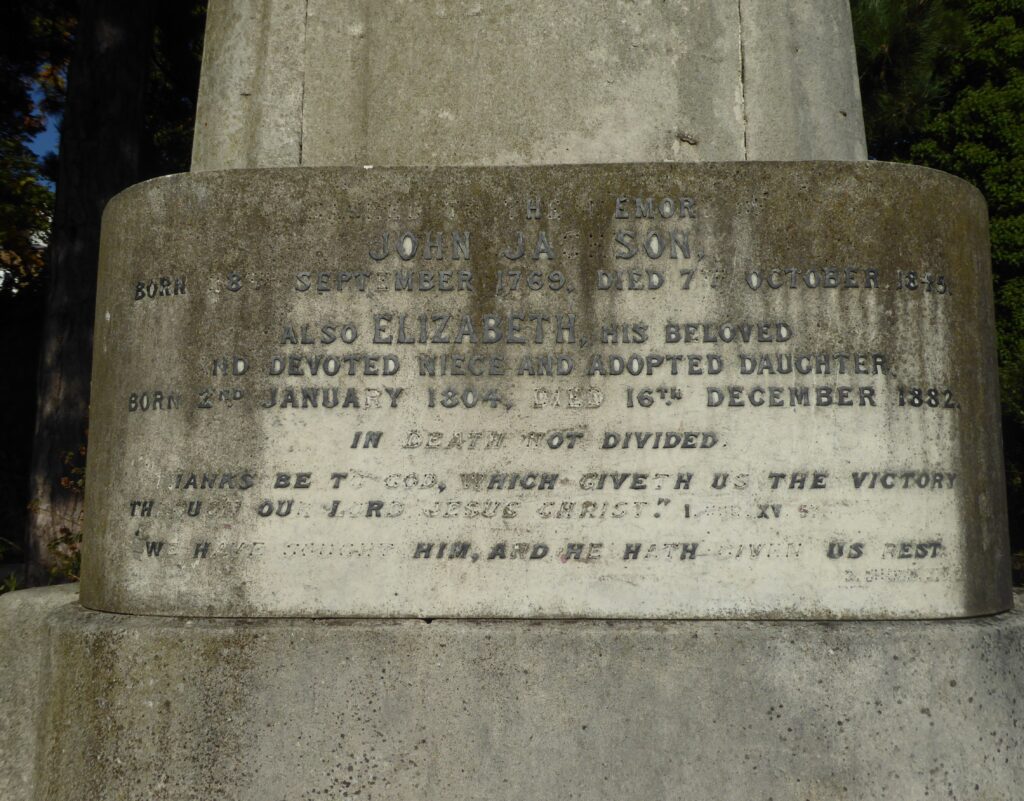

“Gentleman” John Jackson (1769-1845)

In Brompton Cemetery lies “Gentleman” John Jackson, Bare Knuckle Boxing Champion of England. The cognomen reflected his background, his father was a wealthy builder at a time when most pugilists came from the poorer classes. Moreover, John Jackson combined an urbane manner with refined speech and stylish dress. Though a keen amateur boxer, in his early days he worked with his father, and being tall and muscular, was also in demand as an artists’ model for sculptors and painters including Thomas Lawrence.

Remarkably, his fame in the ring was based on only three public matches, one of which he lost. In 1788 he defeated William Fewtrell in Birmingham. A year later he was beaten by George “the Brewer” Ingleston when he slipped on a wet stage breaking a bone in his leg. He offered to be strapped to a chair to continue the fight if his opponent would do the same, but Ingleston refused. He did not fight again until 1795, but it was this final match against the reigning champion, Daniel Mendoza, which assured his fame. Such was his public profile following the bout that he was able to retire from the ring and open a successful Boxing Academy in Bond Street, where he numbered Byron amongst his pupils. The latter described him as “The Emperor of Pugilism.”

In 1814 Jackson helped to establish the Pugilistic Club which regulated prize fighting, exposing crooked behaviour like match fixing, and introducing new rules limiting fights to fists alone with no kicking or hair holding – this last ironic since Jackson had won his match against Mendoza with precisely that expedient, grabbing his opponent’s long hair in one hand while delivering his blows with the other.

Nonetheless, Jackson was a popular figure, organising exhibitions by other boxers to raise money for charities. The lion, symbolising skill and strength, was erected on his tomb in Brompton Cemetery and paid for after his death by friends and admirers.

George Wombwell (1777-1850)

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries boxing matches often took place at fairs, and my second lion sits on the tomb of a frequent visitor to those fairs, but in a different capacity to Jackson. George Wombwell worked as a shoemaker, until the day he bought two boa constrictor snakes on the London docks for the considerable sum of £75. He soon found that he could make more money exhibiting them in taverns than he could making shoes. Scouring the docks he bought more exotic animals from ships trading with Africa, Australia, and South America. He established Wombwell’s Travelling Menagerie, touring the country to exhibit at fairs. Soon he was travelling with fifteen wagons housing giraffes, gorillas, bears, elephants, lions, monkeys, panthers, tigers, and zebra. A brass band travelled in front; garish posters announced their arrival.

The menagerie proved extremely popular at all levels of society, for Wombwell not only profited at the fairs but was also a favourite at the royal court, appearing three times before queen Victoria and her consort. At his death he left three travelling menageries managed by himself and other family members.

Apologists for Wombwell point out that the concept of animal rights was alien to Victorians, that it is a questionable exercise to judge the behaviour of one era by the norms and values of another. But it is difficult to comprehend how anyone could fail to be repelled and saddened by the sight of wild animals imprisoned in cages. Wombwell’s defenders argue that the shows were educational, and indeed the early ones were accompanied by lectures in natural history, and it is understandable that people were fascinated by their first sight of these creatures in the days before ubiquitous natural history documentaries.

The lectures however were soon superseded by animals trained to perform tricks. One of the most egregious displays involved lion baiting with a pack of bulldogs for which tickets were sold for between one and five guineas. When the docile lion Nero failed to be provoked Wombwell replaced him with the more aggressive Wallace whom he had bred in captivity, and who promptly mauled the dogs. Even his contemporaries were prompted to raise questions of animal cruelty, but Wombwell’s only response was that the lions were unharmed and that he would never be so foolish as to risk damage to such valuable pieces of property. Of the dogs he did not comment.

Often the poor creatures in the menagerie died even without being subjected to these torments, for indigenous to hot climates they were ill suited to survival in Britain.Wombwell may have spent a great deal on veterinary care, but his motive was always economic. He was an inveterate entrepreneur able to turn any situation to his advantage. One year at Bartholomew Fair his elephant died enabling his rival Atkins to display a sign advertising “The only live elephant in the fair.” Wombwell responded immediately with a notice proclaiming, “The only dead elephant in the fair.” The latter proved the greater attraction for people could poke and prod the poor carcass as much as they wanted; meanwhile Atkins’ menagerie was deserted.

Wombwell also sold dead animals to medical schools and taxidermists, and specimens can still be found in the zoology museums of Cambridge and Aberdeen, and in Norwich castle and museum. He donated Wallace to the natural history museum in his native Saffron Walden where he remains on display.

Wisely, Wombwell himself, who is buried in Highgate West, chose to rest under a statue of the more compliant Nero.

Frank C. Bostock (1866-1912)

Frank C. Bostock was a great grandson of George Wombwell, born into the travelling show, Bostock and Wombwell, run by his parents. After their death, his older brother took over the show and Frank toured Europe and America with his own travelling menagerie. At Coney Island he established Bostock’s Arena, where audiences numbered 16, 000 a day between 1894-1903.

His animals were claimed by his admirers to be healthy and long-lived, and his entertainments were supplemented by educational talks about habits and habitats, but animal welfare organisations raised concerns about the animals’ living conditions. Nonetheless Bostock became known as “The Animal King” on account of his skill in training wild animals. His supporters wrote of the close bond he had with his animals and of his high standards in care and training, introducing “positive reinforcement.” The photographs of him seated surrounded by a dozen or more lions are appealing, but it seems unlikely that their training was very humane, the more so since he is credited with the realisation that lions are intimidated by upturned chairs which can therefore be used to control them. Nor does the fact that he introduced the first boxing kangaroos speak of a man much concerned with animal wellbeing.

Moreover, Bostock had a cavalier attitude towards human safety. When he returned to England, he set up another show, “The Jungle,” at Earl’s Court, before touring the country. In Birmingham one of his lions escaped and entered the sewers at an open manhole. It made its way roaring under the city causing widespread panic. Bostock’s response was to smuggle out a more biddable second lion in a covered cage and pretend to find and recapture the original lion. The latter facilitated his deception by ceasing to roar. Bostock was hailed as a hero and the publicity increased his takings that evening. Worried about the possible consequences of the free ranging lion however Bostock confessed his deception to the police the next day. They supplied five hundred armed men to assist its recapture, and at midnight, to keep the danger secret from the public, the expedition set out. They chased the lion with shouts and fireworks until it became trapped in a hole in the sewer and Bostock was able to regain possession of it.

Bostock popularised circus shows and amusement parks across America, Australia, Europe, and South Africa. He produced animal training manuals which, disturbingly, are still in print. He completed the transformation begun by his ancestor George Wombwell in democratizing menageries, where previously they had been the prerogative of the wealthy and aristocratic at locations like Versailles and the Tower of London.

I like Bostock’s tomb in Abney Park Cemetery which echoes that of Wombwell, and bears my third crouching lion, but I have little sympathy with his legacy.