“Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night” and “Let Me Die a Youngman’s Death” are two of my favourite poems about death.

“Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

thundered Dylan Thomas.

A more light-hearted Roger McGough pleaded,

“when I’m 104

& banned from the Cavern

may my mistress

catching me in bed with her daughter

& fearing her son

cut me up into little pieces

& throw away every piece but one”

Alas, despite extensive trawling of graveyards, I have never uncovered such a beguiling epitaph. Yet, a select few have eluded what McGough stigmatised as a “clean & inbetween the sheets” death. Let me introduce you to three eighteenth century ladies whose colourful demise ensured that they did not “go gentle.”

Hannah Twynnoy was allegedly the first person killed by a tiger in England. Her story reads like the inspiration for one of Hilaire Belloc’s Cautionary Tales. In 1703 the animals from a travelling menagerie were housed in the rear yard of the White Lion Inn at Malmesbury. Hannah, a servant there, ignored repeated warnings not to tease the animals and persistently taunted the tiger. Tiring of this treatment, the latter escaped his cage and mauled her to death. The epitaph on a stone in Malmesbury Abbey Churchyard records her fate:

In bloom of Life

She’s snatched from hence,

She had not room

To make defence;

For Tyger fierce

Took Life away.

And here she lies

In a bed of Clay,

Until the Resurrection Day.

As a tribute to Hannah in 2003, on the 300th anniversary of her death, Malmesbury girls named Hannah under the age of eleven each laid a single flower on her grave. My own sympathies lie wholly with the tiger.

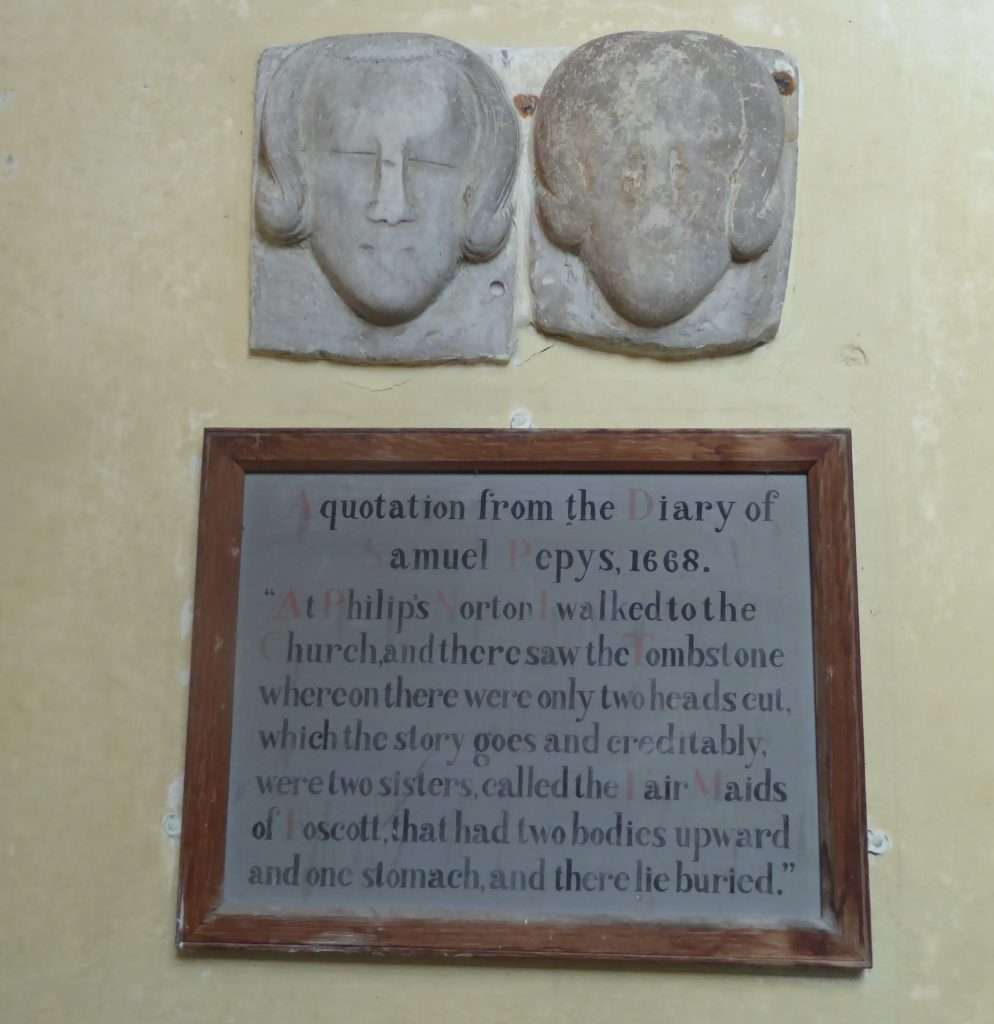

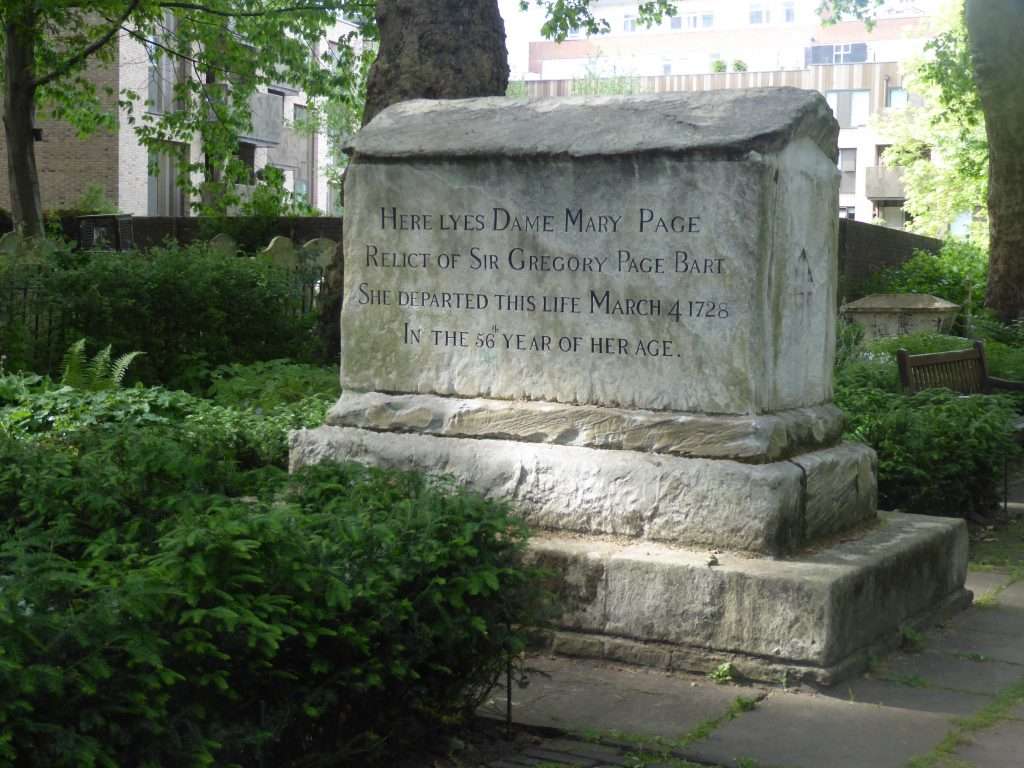

In Bunhill Fields Dame Mary Page draws more attention than the luminaries, Blake, Bunyan, and Defoe, with whom she shares a resting place. In 1728 she sought medical advice for a swelling of the abdomen. Her physician diagnosed a form of dropsy. The inscription which was carved upon her tomb chest at her own request describes the excruciating treatment she received:

IN 67 MONTHS SHE WAS TAP’D 66 TIMES,

HAD TAKEN AWAY 240 GALLONS OF WATER

WITHOUT EVER REPINING HER CASE

OR EVER FEARING THE OPERATION.

Unfortunately, the treatment was clearly not successful. Current medical opinion favours the suggestion that the poor lady had Meigs’ syndrome, a form of ovarian cancer.

F J Baigent and J E Millard in “A History of the Ancient Town and Manor of Basingstoke” tell the story of Alice Blunden, “a fat gross woman (who) had accustomed herself many times to drinking brandy.” In 1764 she imbibed a large quantity of poppy water, a herbal tea, which can function as a narcotic inducing a coma. She fell into a deep sleep from which she could not be wakened, and an apothecary pronounced her dead. Her relations, considering that “the season of the year being hot and the corpse fat, it would be impossible to keep her,” buried her without delay in the Holy Ghost Cemetery. A few days later boys playing nearby heard “groans and dismal shriekings” and a voice crying “Take me out of my grave.” When the coffin was opened “ the corpse puffed up as it had been a bladder and the joiner had made the coffin so short that they were fair to press upon her and keep her down with a stick while they nailed her up.” The body bore signs of self-inflicted injuries as Alice had sought to escape. Since there was now no sign of life, they returned Alice to her grave until the coroner could be summoned next day. Disinterred for the second time she had “torn off a great part of her winding sheet, scratched herself first in several places, and beaten her mouth so long that it was all in gore blood.” This time the coroner pronounced her definitely dead, and Parliament fined the town for its negligence. Alice appears in a bronze panel decorating the Triumphal Gateway, erected in 1991 at the Top of the Town leading into the old town of Basingstoke, where she hammers for all eternity on her coffin lid in a moonlit churchyard.