I had long harboured a desire to swim in the River Thames. Conscious of my own limitations, this was no ambitious plan to cover the length (over two hundred miles, I don’t think so) nor to venture into the tidal waters below Teddington Lock. The Port of London Authority strongly discourages both activities with dire warnings of powerful tides overpowering the strongest of swimmers; eddies and undertows sucking them under in seconds; danger from water traffic in the form of clippers, ferries and working boats; and the biting cold of the water leading to crippling breathing spasms.

Something more modest then, a gentle width somewhere in the Middle Reaches of the Thames. Here opinion was divided. Public Health England warned of gastrointestinal diseases from contaminated surface run off, and from water containing raw sewage routinely pumped into the river after heavy rains; the possibilities of contracting Leptospirosis or Weil’s disease from animal urine; high recorded levels of microplastics in the water; and dangers of collision with leisure traffic. Enthusiasts, by contrast, rhapsodised about an arcadian Thames: a sparkling , idyllically pastoral river with 125 species of fish, over four hundred invertebrates, and flourishing flora.

By dint of slightly overemphasising the latter perspective, I persuaded a friend to accompany me, and we took to the river at Clifton Hampden. Our respective partners, both non-swimmers and of the firm conviction that immersion, in any volume of water greater than that required to fill a decent sized bathtub, is a supreme folly, sat on the bank guarding the clothes. They wore expressions which said No Good Will Come of This.

And it must be confessed that we entered the water with some trepidation, feeling our way cautiously out into the river, wary of what lay beneath our feet, dreading that moment when the cold-water hit our stomachs, alert to the dangers from passing boats, and with mouths firmly closed. But once in the river the pleasure of swimming, pushing weightlessly through the water, took over. It was not cold, it did not look particularly polluted, and folk waved cheerfully from passing boats. Across and back, and we turned around, enthusiastic to repeat the exercise.

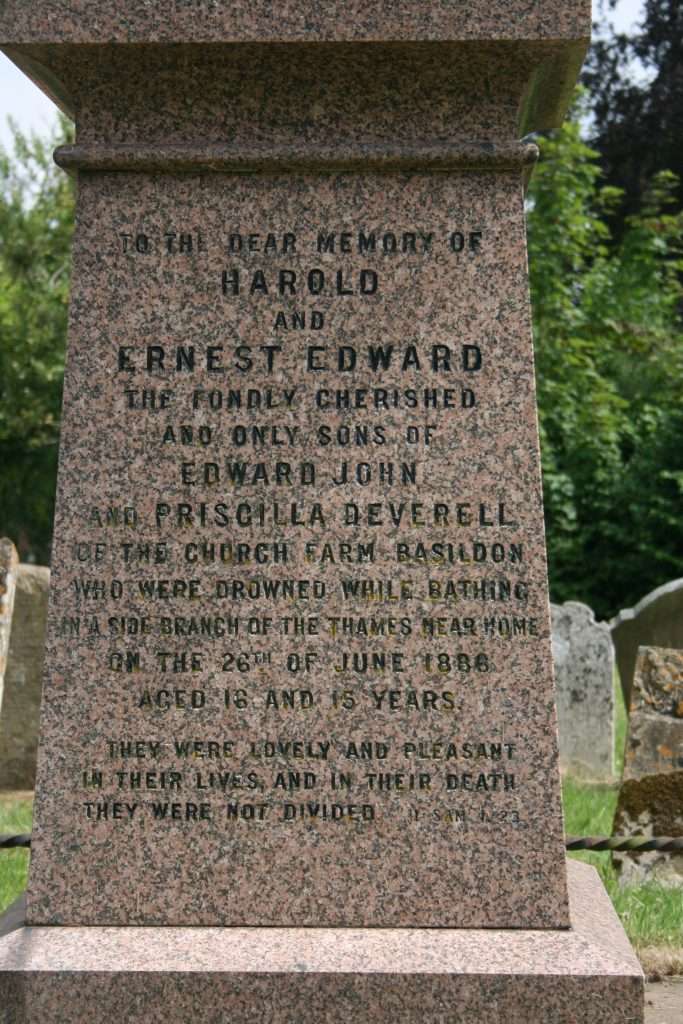

Later in the pub we regaled our sceptical partners with the delights of Wild Swimming. But there was a sobering coda. Walking along the Thames Path a few miles downriver, we paused to admire the thirteenth century flint church of Saint Bartholomew at Lower Basildon, and in the churchyard discovered the hauntingly beautiful grave of Harold and Ernest Edward Deverell. Aged fifteen and sixteen, they drowned while bathing close by in 1866. The marble sculpture of the two boys, in their old- fashioned bathing trunks, and looking far younger than their teenage years, is heart-rending.

They were lovely and pleasant in their lives, and in their death they were not divided

A guide to the church records starkly: “ One brother got into difficulties and the other went to his aid: sadly, both drowned.”

There is a small risk even in those little adventures which look quite safe on a summer’s afternoon, and the boys’ deaths were tragic. Yet too much caution renders human existence a tepid affair, with little point to life if we act in constant fear of its end.