Henry Cole (1808-1882) combined administrative skills with a practical flair for production and design. Between 1837-40 when he worked as an assistant to Rowland Hill, these twin talents became apparent. He played a key role in the introduction of the Penny Post and was responsible for the design of the world’s first postage stamp, the Penny Black.

Under the pseudonym of Felix Summerly he created his own award-winning designs, including a tea service produced by Minton. But it was his organisational talents which were truly breath taking. In 1851 Cole proposed an International Great Exhibition of Culture and Industry to celebrate, and to stimulate the improvement of, modern manufacture and decoration. He sought to promote international trade, providing a platform for British products; British manufacturers were to get the best locations at the exhibition. Despite opposition from Parliament, and the press doubting the success of his venture, he launched his scheme, and under his management it became an enormous success, the first in a series of World Fairs.

Joseph Paxton designed the massive glasshouse, the Crystal Palace, in which the Great Exhibition was held at Hyde Park. The prefabricated structure with a cast iron frame was an engineering triumph. Within it more than a million objects were displayed, with sectors showcasing raw materials, machinery, manufactured goods, and fine arts. A massive pink glass fountain stood in the centre. William Morris found the latter in bad taste, but the public loved it.

Exhibits included the entire process of cotton production, electric telegraphs, steam powered machines, a lighthouse, locomotives, scientific tools, microscopes, barometers, surgical instruments, kitchen appliances, an early adding machine, an umbrella which doubled as a weapon, a neo-gothic medieval court designed by Pugin, Indian textiles, musical instruments including a folding piano, silks, porcelain, tapestries, majolica. From glass vitrines the Koh-I-Noor diamond and the eighth century Tara Brooch flaunted their mystique. Who would not have wanted to be there amid the extravagant opulence and exciting new inventions? Everyone did: in the sixth months of the exhibition six million people, a third of the population, visited. The railways offered discounted tickets and Thomas Cook arranged one of his earliest excursions, bringing 150,000 people from the North and Midlands.

The Crystal Palace witnessed the first international chess tournament, and played host to the first modern pay toilets, use of the latter priced at one old penny, bringing a new coy euphemism into the English language. Canny businessman that he was, Henry Cole persuaded Schweppes, the world’s first soft drink company, to sponsor the exhibition, and organised a tempting line in souvenirs with stereoscopic cards, fans, and plates. A huge financial as well as a popular success, the exhibition made a profit of £186,000, around £34 million in today’s money.

This enabled Cole to embark on his next great project, the founding of the South Kensington Museum for Education in Applied Art and Science. With the profits of the Great Exhibition, he organised the purchase of land in South Kensington, supervised the building works, and became the first director of the museum from 1857-73. It subsequently became the Victoria and Albert museum, specialising in decorative arts and design, while the Science and Natural History museums became independent entities. Always concerned with the educational function of the collections, Cole also helped to develop the Royal Colleges of Art and Music, and the Imperial College of Science and Technology.

Under Cole’s guidance the Victoria and Albert Museum became a magnificent show case for outstanding designs of furniture, textiles, glass and metal work, and ceramics. Determined to instruct people in superior design and good taste, Cole also set up a Gallery of False Principles, displaying what he perceived as bad designs. These included fabrics and wallpapers with naturalistic images of foliage and flowers, which he considered excessive and illogical ornamentation. Their failings were spelled out on their labels, and alongside them sat “correct” versions. The Gallery proved popular and caused much amusement, but the display was closed after two weeks following complaints from manufacturers whose work was pilloried there. But the memory of the intended lesson lives on, for Charles Dickens, more sentimental and sympathetic towards anyone who might like something pretty, satirised Cole’s judgment in Hard Times when the Utilitarian School Board Superintendent visits Gradgrind’s schoolroom:

Now, let me ask you girls and boys, Would you paper a room with representations of horses?’

After a pause, one half of the children cried in chorus, ‘Yes, sir!’ Upon which the other half, seeing in the gentleman’s face that Yes was wrong, cried out in chorus, ‘No, sir!’—as the custom is, in these examinations.

‘Of course, No. Why wouldn’t you?’

A pause. One corpulent slow boy, with a wheezy manner of breathing, ventured the answer, Because he wouldn’t paper a room at all, but would paint it.

‘You must paper it,’ said the gentleman, rather warmly.

‘You must paper it,’ said Thomas Gradgrind, ‘whether you like it or not. Don’t tell us you wouldn’t paper it. What do you mean, boy?’

‘I’ll explain to you, then,’ said the gentleman, after another and a dismal pause, ‘why you wouldn’t paper a room with representations of horses. Do you ever see horses walking up and down the sides of rooms in reality—in fact? Do you?’

‘Yes, sir!’ from one half. ‘No, sir!’ from the other.

‘Of course no,’ said the gentleman, with an indignant look at the wrong half. ‘Why, then, you are not to see anywhere, what you don’t see in fact; you are not to have anywhere, what you don’t have in fact. What is called Taste, is only another name for Fact.’ Thomas Gradgrind nodded his approbation.

‘This is a new principle, a discovery, a great discovery,’ said the gentleman. ‘Now, I’ll try you again. Suppose you were going to carpet a room. Would you use a carpet having a representation of flowers upon it?’

There being a general conviction by this time that ‘No, sir!’ was always the right answer to this gentleman, the chorus of No was very strong. Only a few feeble stragglers said Yes: among them Sissy Jupe.

‘Girl number twenty,’ said the gentleman, smiling in the calm strength of knowledge.

Sissy blushed, and stood up.

‘So you would carpet your room—or your husband’s room, if you were a grown woman, and had a husband—with representations of flowers, would you?’ said the gentleman. ‘Why would you?’

‘If you please, sir, I am very fond of flowers,’ returned the girl.

‘And is that why you would put tables and chairs upon them, and have people walking over them with heavy boots?’

‘It wouldn’t hurt them, sir. They wouldn’t crush and wither, if you please, sir. They would be the pictures of what was very pretty and pleasant, and I would fancy—’

‘Ay, ay, ay! But you mustn’t fancy,’ cried the gentleman, quite elated by coming so happily to his point. ‘That’s it! You are never to fancy.’

‘You are not, Cecilia Jupe,’ Thomas Gradgrind solemnly repeated, ‘to do anything of that kind.’

‘Fact, fact, fact!’ said the gentleman. And ‘Fact, fact, fact!’ repeated Thomas Gradgrind.

‘You are to be in all things regulated and governed,’ said the gentleman, ‘by fact. We hope to have, before long, a board of fact, composed of commissioners of fact, who will force the people to be a people of fact, and of nothing but fact. You must discard the word Fancy altogether. You have nothing to do with it. You are not to have, in any object of use or ornament, what would be a contradiction in fact. You don’t walk upon flowers in fact; you cannot be allowed to walk upon flowers in carpets. You don’t find that foreign birds and butterflies come and perch upon your crockery; you cannot be permitted to paint foreign birds and butterflies upon your crockery. You never meet with quadrupeds going up and down walls; you must not have quadrupeds represented upon walls. You must use,’ said the gentleman, ‘for all these purposes, combinations and modifications (in primary colours) of mathematical figures which are susceptible of proof and demonstration. This is the new discovery. This is fact. This is taste.’

The girl curtseyed, and sat down. She was very young, and she looked as if she were frightened by the matter-of-fact prospect the world afforded.

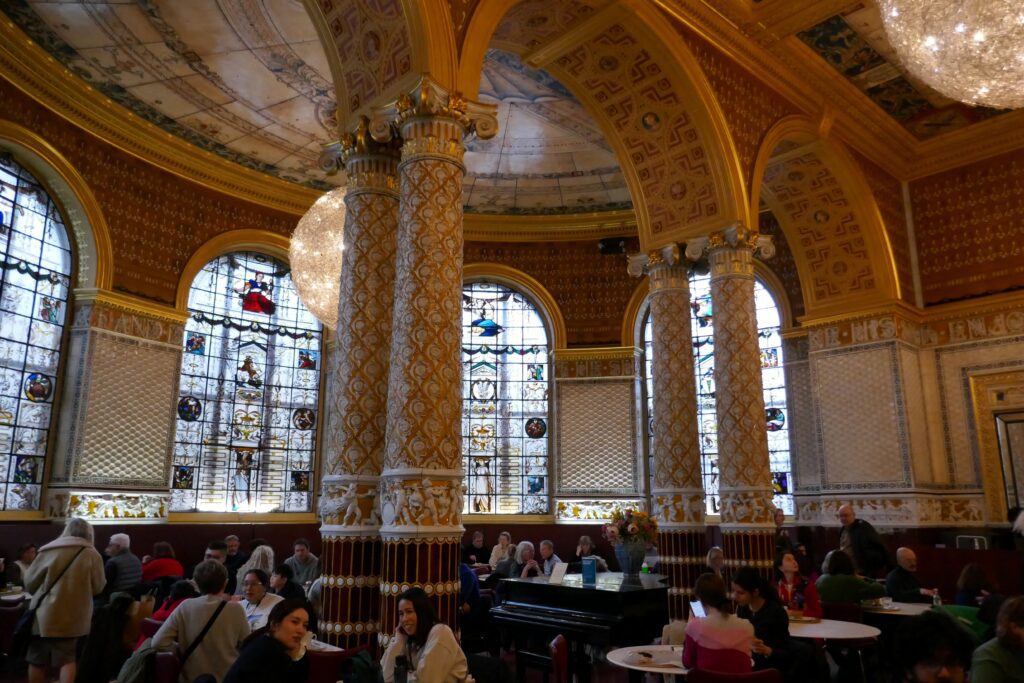

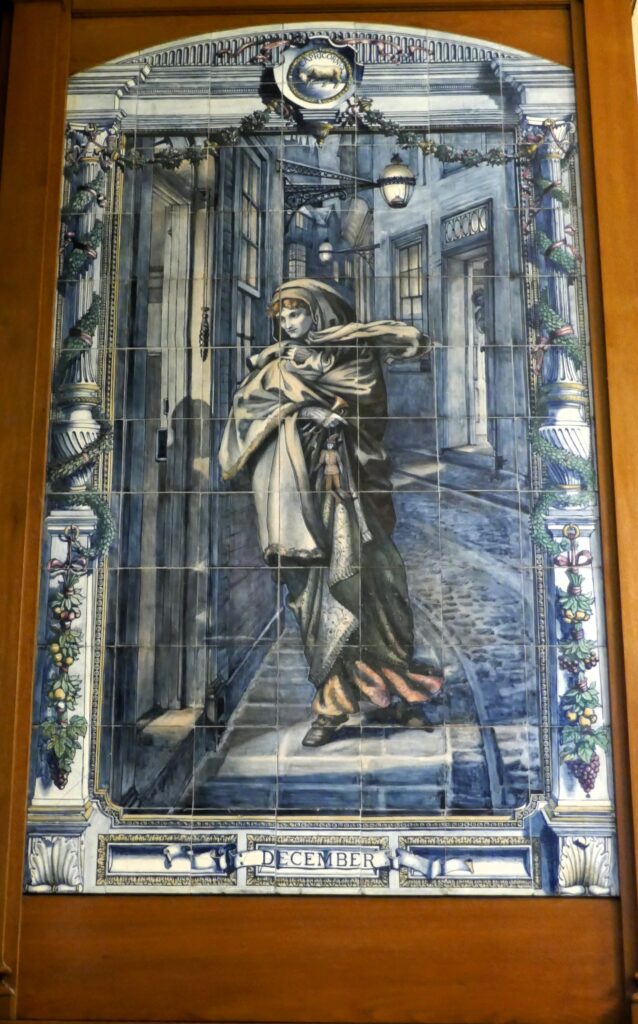

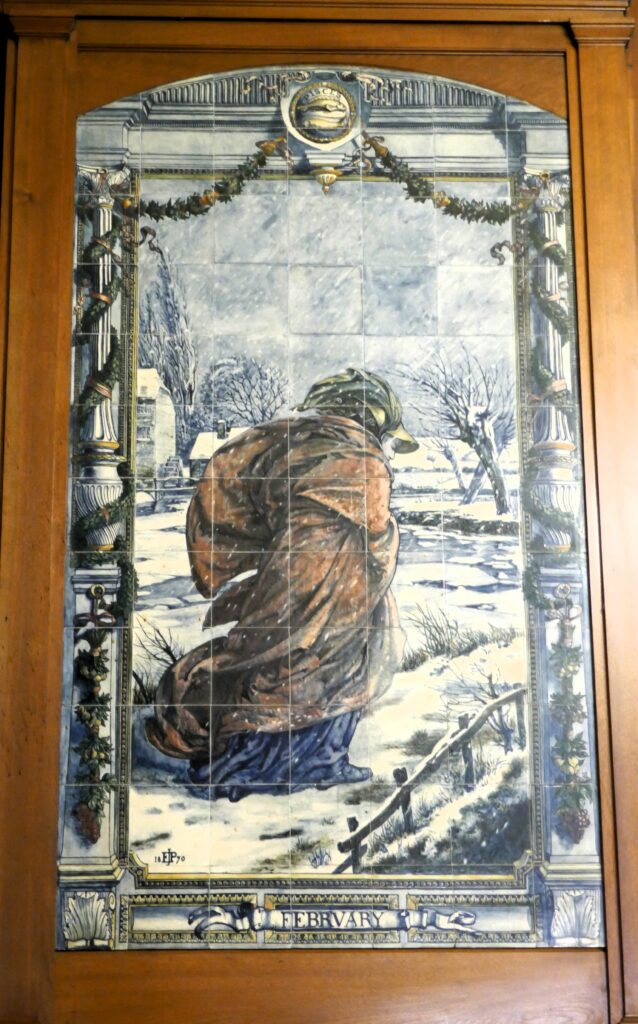

Yet, notwithstanding a little pomposity and a common weakness for conflating his own taste with good taste, Cole gave us something very precious in the V and A. It is magical at any time but especially in winter when the rainbow colours of the textiles and costumes, the gleam and shine of the jewellery and metalwork, triumph over the prevailing gloom of the December skies. I choose a few favourite objects to visit, perhaps Shah Jahan’s winecup or Tipu’s tiger, the carved oak facade of Paul Pindar’s sixteenth century house or the Hereford screen, or Dale Chihuly’s extravagant glass sculpture, before heading for the refreshment rooms.

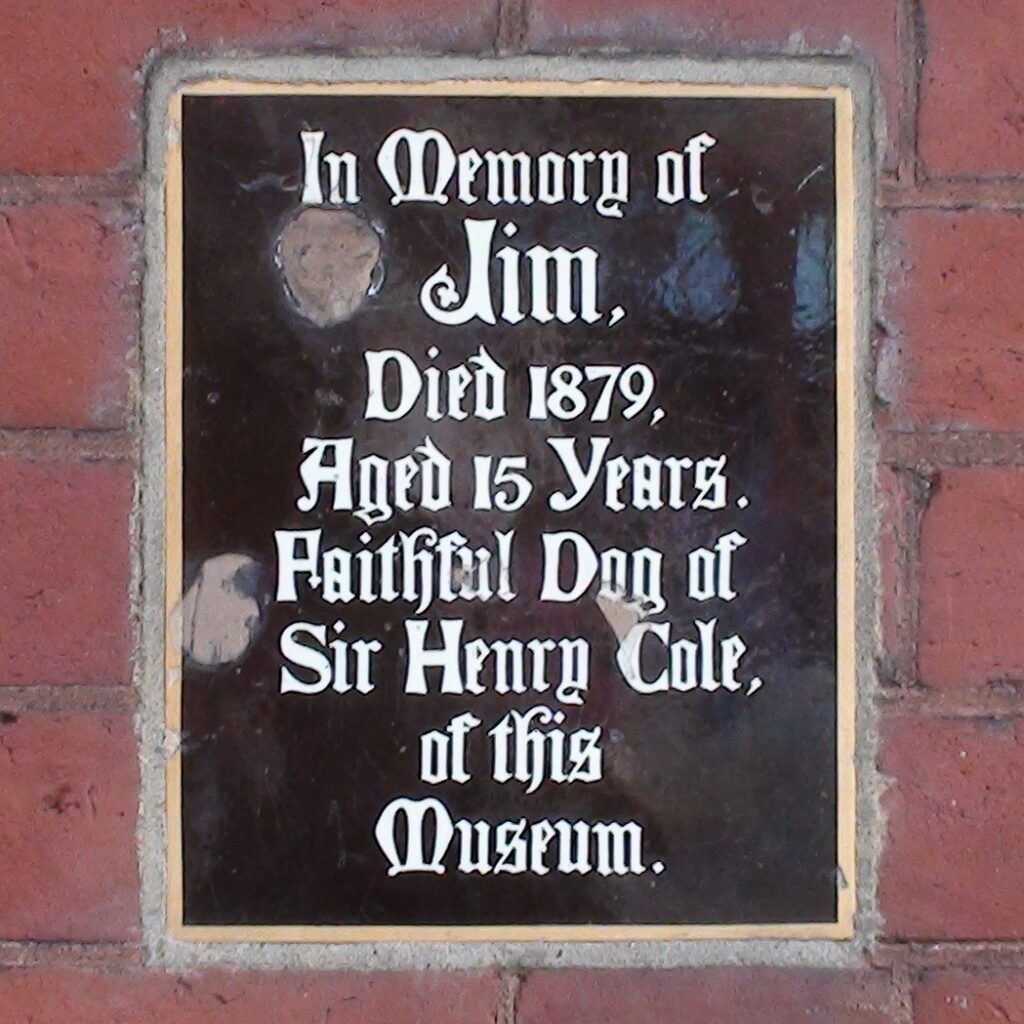

The V and A was the first museum in the world to have a catering service, and what sublime trio of rooms they are. Ensconced in the warmth with a cup of tea and a bun, surrounded by the magnificently eclectic décor featuring ceramics, stained glass, panelling and enamelling, in the Gamble, Poynter or Morris Room, all is right with the world. I could go into semi-hibernation here, sleeping at night in the Great Bed of Ware, by day wandering the labyrinthine corridors from one gallery to another, taking my meals in the refreshment rooms, emerging to the garden court only in Spring. There to meet with the spirit of Jim, Henry Cole’s Yorkshire terrier, who accompanied his master on his daily site inspections as the museum buildings rose from the ground, and who is buried somewhere here in the garden.

And at this time of year, I remember Henry Cole for something else, because in 1843 he designed and produced the first Christmas card. Depicting three generations his family raising a toast, with representations of charity and almsgiving around the margins, it is surely an image with which Dickens would have sympathised.

When I was a child our living room filled with cards at Christmas, for my grandparents came from the days of extended families and had a wide circle of friends. We strung the cards in loops across the chimney breast, and cascading down the walls. More jostled on the mantlepiece. Others surrounded and concealed the fruit bowl on the sideboard with its seasonal cargo of tangerines wrapped in tissue paper which when rolled into a cylinder and lit would float magically and weightlessly up to the ceiling. The post came twice a day: cards fell through the letterbox before I left for school, and a second pile arrived in the afternoon, saved for me to open when I came home.

Now there are fewer cards each Christmas, my grandparents long gone and my own contemporaries beginning to slip away. Moreover, the world has changed. Christmas greetings arrive by email. It is an easier way to communicate, quicker, more immediate, and very much cheaper. For in the 50s and 60s not only were boxes of Woolworths cards in the reach even of a child’s pocket money, but so were stamps. And if an envelope contained no other enclosure than a card, and if the flap were tucked in rather than sealed, then an even cheaper stamp would guarantee delivery. Today the annual purchase of books of stamps offers a sharp lesson in inflation, “How much?” we gasp in horror. Yet I cannot resist the pleasure of choosing and writing cards, and while it is nice to receive the emails, I am glad when friends still send those cheery, colourful, paper greetings which nudge each other on my bookshelves basking in the reflected lights of the tree.

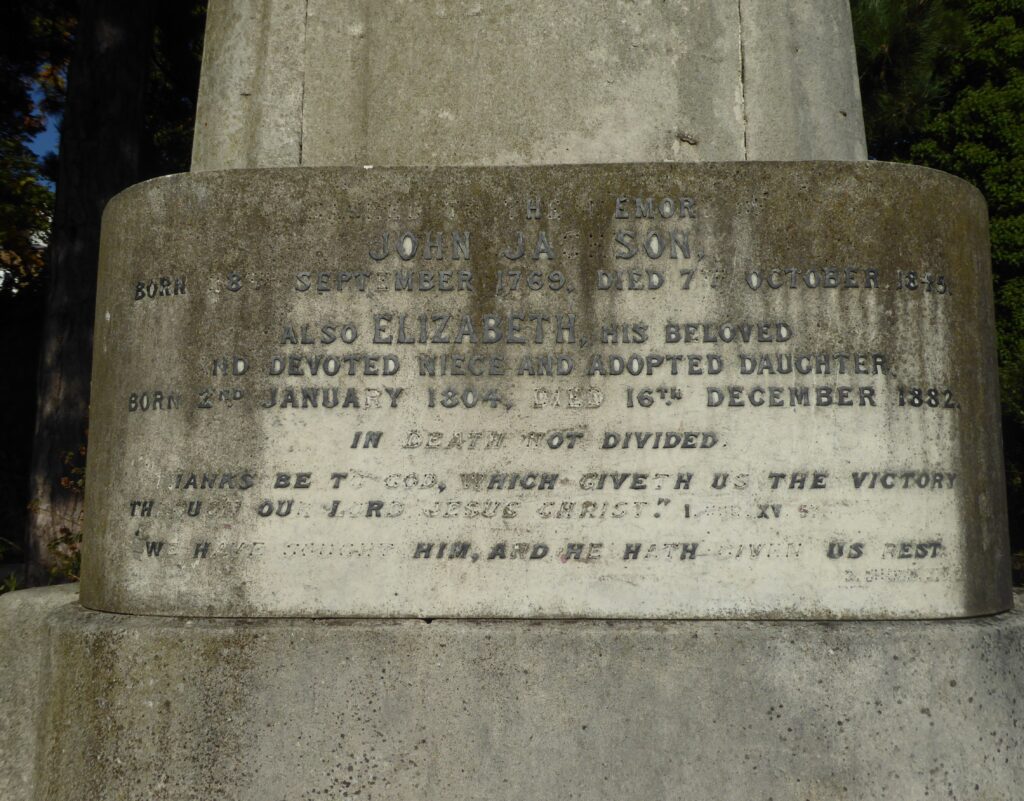

So, thank you Henry Cole for the Victoria and Albert, and for Christmas cards. When I first visited your grave in Brompton, it looked a little sad and neglected, but last week I was not your only visitor for someone had taken ivy and plaited a Christmas wreath for you. Merry Christmas, Henry Cole.