Though I have chosen to live in a quirky old house in an English village, yet I am susceptible to the attractions of a minimalist, modernist, city apartment. So I was eager, when on holiday in Marseilles, to visit Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation.

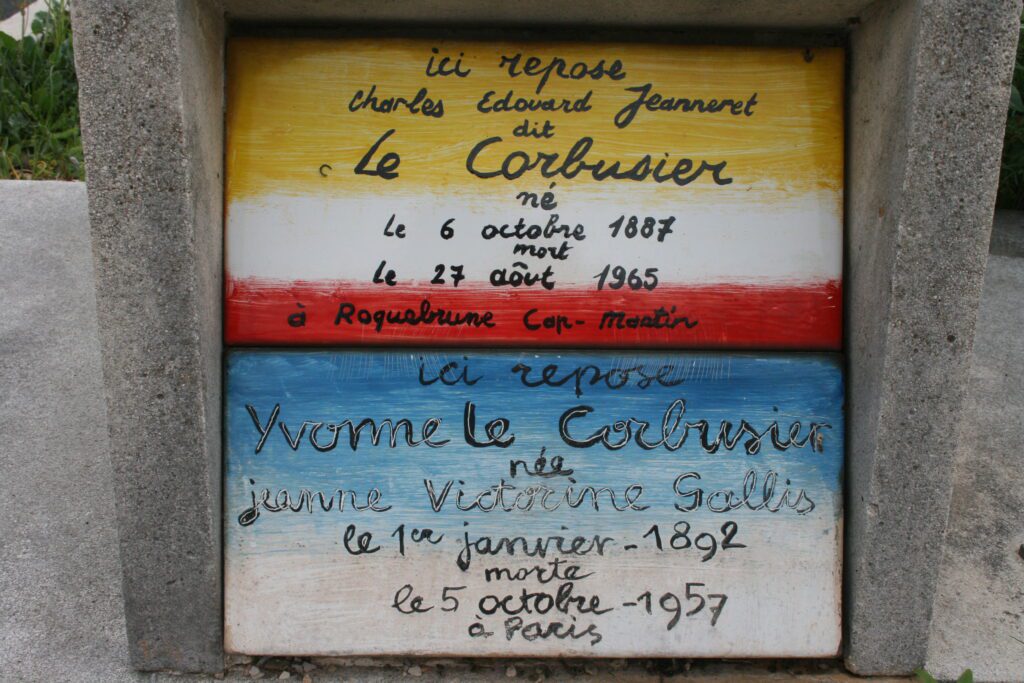

Le Corbusier was the pseudonym Charles Edouard Jeanneret (1887-1965), architect, urban planner, painter, writer.

Le Corbusier had a great deal of confidence, boundless energy, and a talent for memorable epithets. “A house is a machine for living in,” he declared and set about creating houses and apartments in accordance with his dictum. Buildings he reasoned should be purely functional, with form following function. (This would appeal to my friends in the museum world who rail against architectural egos failing to consider the needs of their exhibits.)

In Vers Une Architecture, a polemical collection of essays from the 1920s, he elucidated the approach of the Modern Movement, outlining his Five Points of a New Architecture, enumerating the principles on which his designs were based. His houses were to be lifted off the ground with pilotis – slim, reinforced, concrete columns – bearing the weight of the structure, allowing free circulation at ground level, and avoiding dark and damp parts of the building. There should be a flat roof terrace with potential for a garden. The façade should be free of decoration, without ornament: dismissing the then popular eclecticism and art deco, he argued that “modern decoration has no decoration.” Ribbon windows should run the length of the building to provide light and views. There should be an open floor plan with no load bearing partition walls.

For his materials, Le Corbusier embraced glass, steel, and concrete, in pursuit of stronger, lighter buildings.

Contending that houses should be built on a human scale, he developed his Modulor Man to determine the ideal amount of living space required. The Modulor was an anthropometric scale of proportions based on the human body, specifically that of a six-foot-tall (1.83m) man with his arm raised to a height of seven feet and four inches (2.26m), segmented into the golden ratio (1. 61) and scaled up or down using the Fibonacci series. This universal system of proportions, he inferred, would reconcile mathematical order and human function, bringing rationality and harmony not just to buildings but to all aspects of design from doorknobs to cities. Critics have pointed out that the height of six feet was a rather arbitrary choice and Le Corbusier did not deny this, joking that he had chosen that specific height because “in English detective novels, the good-looking men, such as policemen, are always six feet tall.”

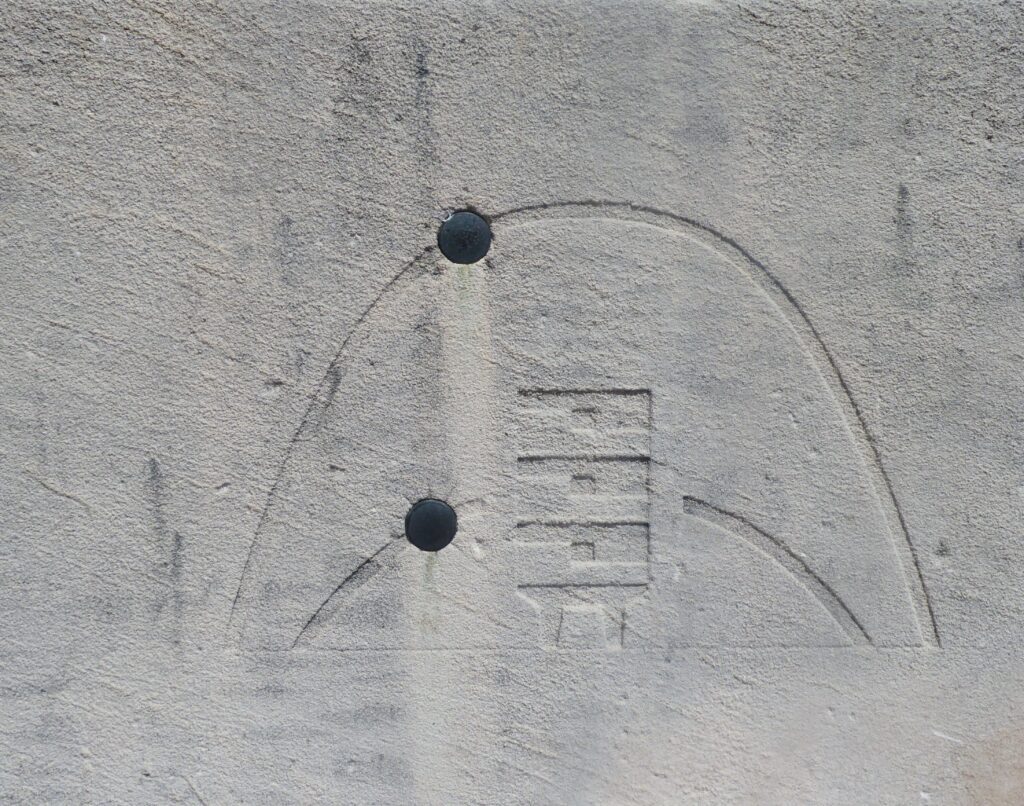

Le Corbusier’s early commissions were private houses for wealthy individuals, but in 1947, Raoul Dautry, the Minister for Reconstruction and Town Planning, commissioned him to create an apartment block in Marseilles. Completed in 1952, the Unité d’Habitation, better known as the Cité Radieuse, is the embodiment of the five points of modern architecture which he had outlined twenty years earlier: it is elevated above the ground with pilotis; on the flat roof is with a running track and a small theatre; there is a free facade; and uninterrupted banks of windows form a horizontal band around the building.

Into this béton brut (rough cast concrete) framework Le Corbusier slotted his modules “like wine bottles in a rack.” Each module was three stories high and contained two apartments, both with dual height living space, interlocking around a corridor, so that corridors were only required on every third floor. Every apartment was dual aspect, running the full width of the building, with its own terrace and brise soleil. Residents had a choice of twenty-three different interior configurations for their units, which ranged from one person to family sizes. The open floor plan came with steel columns which could be moved and removed, to form partitions. Two double width corridors like interior streets ran the length of the building, with shops, eating places, a hotel, an art gallery, nursery, and recreational facilities.

Le Corbusier designed all the furniture, fittings, carpets, and lighting for his apartments. The kitchens were equipped like laboratories. The furniture was mass produced, for he embraced Fordism. Leather chairs were made with a tubular steel frame, they were not decorative, but “useful tools.” Deploying his habitual bombastic maxims he proclaimed, “chairs are architecture, sofas are bourgeois,” and favoured “objects which are perfectly useful, convenient, and have a true luxury which pleases our spirit by their elegance and the purity of their execution and the efficiency of their services.”

And if his hortatory writings are a little wearing, still there is no question that more than seventy years since its inception this building remains a delight with its light filled apartments, labour saving devices and clever minimalist furniture. It comes as no surprise that though they were designed as affordable housing, the apartments today are mainly occupied by long-term middle-class residents who are passionate about their vertical garden city.

View from the roof towards the Mediterranean

And yet, while I delight in this architectural gem, with its views of the Mediterranean from the roof, and at its feet a verdant park, I would not live there, for it is in suburbia, surrounded by dull streets far from the glamorous, edgy beating heart of Marseilles. Offer me the Barbican, gloriously ensconced in the very heart of London and I would wave my rural life goodbye without a backward glance, but not for dreary, unnatural, stifling suburbia.

Small wonder then that Le Corbusier’s work as an urban planner holds none of the allure for me that his architecture does. He may have had the laudable aim of improving living standards in overcrowded cities by providing cheap public housing, but his planned cities repel me. In 1922 he presented his model Ville Contemporaine, an imaginary city for three million inhabitants who would live in identical sixty storey apartment blocks, a “city in the sky.” He envisaged zoning with strict divisions of the city into commercial, business, entertainment, and residential areas. In 1925 he elaborated on this with his Plan Voison for the redevelopment of a large part of Paris. He planned to bulldoze the narrow streets, monuments, and overcrowded houses in the working-class neighbourhoods, replacing them with giant towers, symmetrical, standardised skyscrapers, uniformly laid out in regimented settings in an orthogonal street pattern, with wide traffic corridors running between the vertical architecture. Absurdly he asserted that “a curved street is a donkey track, a straight street a road for men.” Again, zoning and the separation of activities was at the heart of his plan. Happily, neither model was ever realised.

He was able however to implement his city planning ideas on a huge scale when, after Indian independence, Nehru invited him to design the new city of Chandigarh. There, putatively seeking to raise the quality of life for the working class, he built his city with segregated residential, commercial, and industrial areas, government buildings and parks. These disconnected rectangular sectors separated by broad streets and fast-moving traffic are bleak and depressing. Moreover, he consciously isolated poor communities displaying casual contempt for the people he was supposedly helping: “The technocratic elite, the industrialists, financiers, engineers, and artists (will) be located in the city centre while the workers (will) be moved to the fringes of the city.” There are individual treasures in Chandigarh, not least in the Capitol Complex, but the housing projects are regimented and inhuman with no reference to local tradition, and the overall impact is one of sterility.

Of course, a lack of enthusiasm for his urban planning did not deter me from seeking out Le Corbusier’s grave. He is buried in Roquebrune in a cemetery overlooking the Cote d’Azur where he bought a plot when his wife died in 1957. He designed a grave for them both, and it comes as no surprise to find a béton brut slab sitting alongside a cylindrical plant holder of the same material. A blue and white enamel plate, the blue representing the sea, commemorates his wife. A second plate in yellow and red, representing sunlight and sky, records his own death in 1965.

But behind his presence there in Roquebrune lies a story which does not present him in a very edifying light.

Eileen Grey, the Irish architect and furniture designer, had designed a villa, E-1027, at Roquebrune Cap Martin in 1929 for herself and her then lover Jean Baldovici. When they separated Baldovici kept the house and invited his friend Le Corbusier to make use of it. While he was there in 1938-9 Le Corbusier, without seeking permission, painted eight murals over the white walls of the villa. For Grey this was an act of vandalism, a violation of her creation.

Ironically Grey’s villa was much like Le Corbusier’s own early works, a modernist building raised on pilotis, with a roof garden, horizontal windows, and a free façade. Originally, Le Corbusier had admired it, and Grey had been gratified by his praise. But the architectural critic Rowan Moore suggests that Grey’s work was superior to that of le Corbusier, with a softer, more naturalist interior making the home a living organism as opposed to the colder, harsh, angular lines of his machines for living. Moreover, Moore describes Le Corbusier’s murals as crude and garish with sexist undertones making snide references to Grey’s bisexuality and relationship with her ex-partner. He suggests that Le Corbusier was outraged that a woman could create work in the style he considered his own and, “seemingly affronted that a woman could create such a fine work of modernism…asserted his own dominion, like a urinating dog over the territory.” “As an act of naked phallocracy Corbusier’s actions are hard to top,” Moore avers. Others have suggested that the murals reflect a psychosexual obsession with Grey and Corbusier’s frustration at being unable to possess her. Certainly, he was disturbingly obsessed with the house making repeated attempts to purchase it. When this failed, he bought land right up against the boundary wall of E-1027 and built his own cabanon de vacances there, overlooking the villa. He visited every summer from 1953-65, swimming every day beneath the house. Indeed, it was while swimming there that he died of a heart attack.

In 2021 a restoration of the villa was completed.

Le Corbusier, Vers une Architecture (first published 1923)

Rowan Moore, Eileen Grey’s E- 1027 in The Guardian, 30 June 2013, and 2 May 2015