The first sign appeared in late January when I noticed that the wine rack had been pushed to one side to accommodate a generous collection of beers. The Six Nations Championship was imminent, and my partner was making his preparations. When I was teaching I always received two forewarnings as the Head of Games would hand out Sweepstake Charts. A little judicious questioning at home usually enabled me to surprise the staff room with the moderate accuracy of my predictions.

Now there is only the one alert signifying that during the coming six weeks I will be periodically banned from the television room unless I guarantee To Remain Silent or at least Not To Ask Stupid Questions. (This stipulation rises to a crescendo during the cricket season.)

The temptation to watch some exceptionally large men apparently bent on inflicting the maximum amount of pain on one another is not great and I rarely infringe the ruling. Occasionally, under the mistaken impression that a match cannot yet have begun or must be over, I encounter the pre- or post-match discussion. Once I recognised one of the pundits who had been on my PGCE course many years ago. My partner has never been more impressed: “Lock Forward,” he murmured in awed tones, “three caps in the 1989 British Lions tour of Australia. Part of the England side that won the Five Nations Grand Slam in 1991. You knew him? You never mentioned this before?”

“Well, I hardly knew him, we just did our teacher training in the same department.” I dredged my memory. “He was the only one who avoided a scolding if he missed classes, and the first to be offered a job.” A faint recollection stirred, “I think it was in quite a prestigious school, but they didn’t have any slack in the English department, so they offered him some junior Latin. We were all impressed until he revealed he only had O-level Latin. It was obviously the rugby they were after.” My partner gave me a look of contempt, clearly I did not recognise the importance of my brief encounter.

The only other reminiscence I could conjure involved standing chatting to the great lock forward as we waited to go into the examination hall. Suddenly he was joined by half a dozen of his mates, and as deep, hearty voices resounded, I found myself trapped in a forest of massive denim thighs: “It was like being surrounded by giants. Literally, I was at eye level with all these huge thighs, while voices boomed above me.” “The second row,” said my partner with a weary and withering sigh, “are always very tall.”

This was the longest discussion we ever had of rugby until we took a holiday in the south of France. There in Menton, at the top of the Colla Rogna hill, on the site of the old castle above the town, sits a stunning little cemetery. Its fortunate occupants, shaded by the cypress trees, can view the harbour and the promenade, the Mediterranean stretching in one direction to the Italian Riviera and in the other to Cap Martin, and all beneath an intense cerulean sky. We climbed up through the narrow streets of the old town, and at the top I wandered through the section of the cemetery generously provided for the residents of foreign colonies. In the nineteenth century large numbers of minor poets, academics, and clergymen from chilly, northern countries brought their agues, distempers, and infirmities to the sunny place, though they seldom survived for long.

A sudden shout from my partner drew my attention to one flat and one upright marble stone, surrounded by beribboned railings and fronted by a collection of plaques.

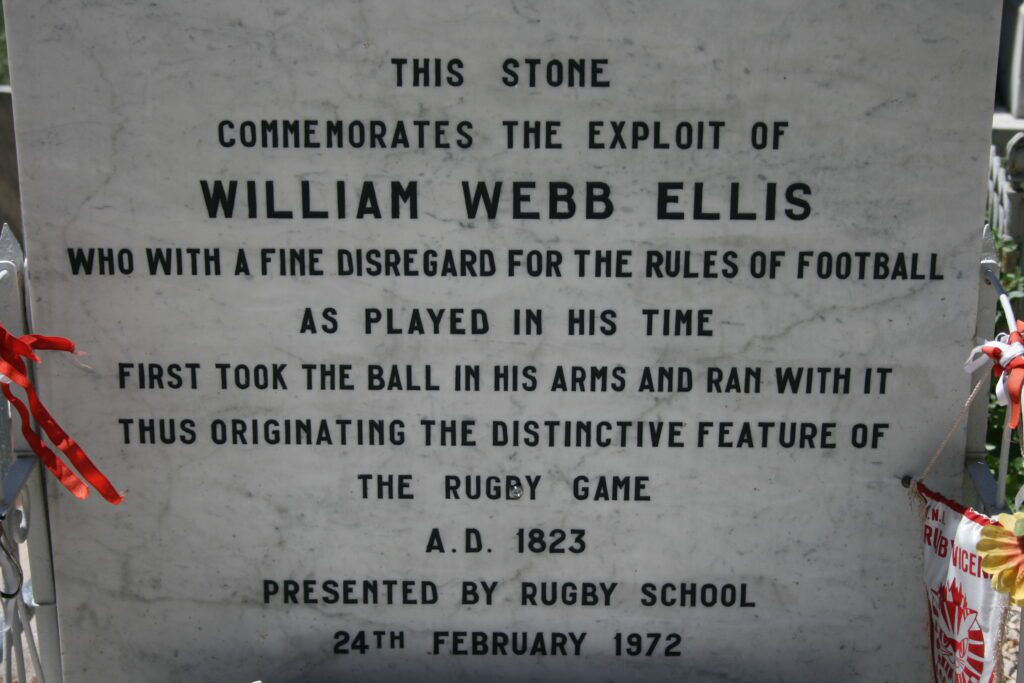

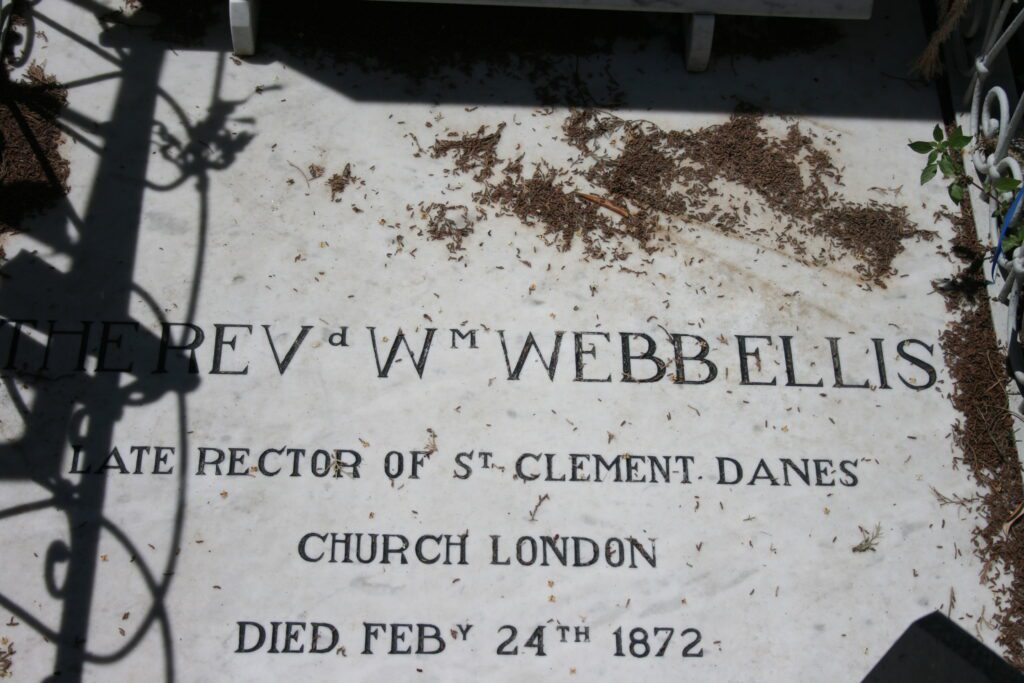

The upright stone provided all the explanation I needed:

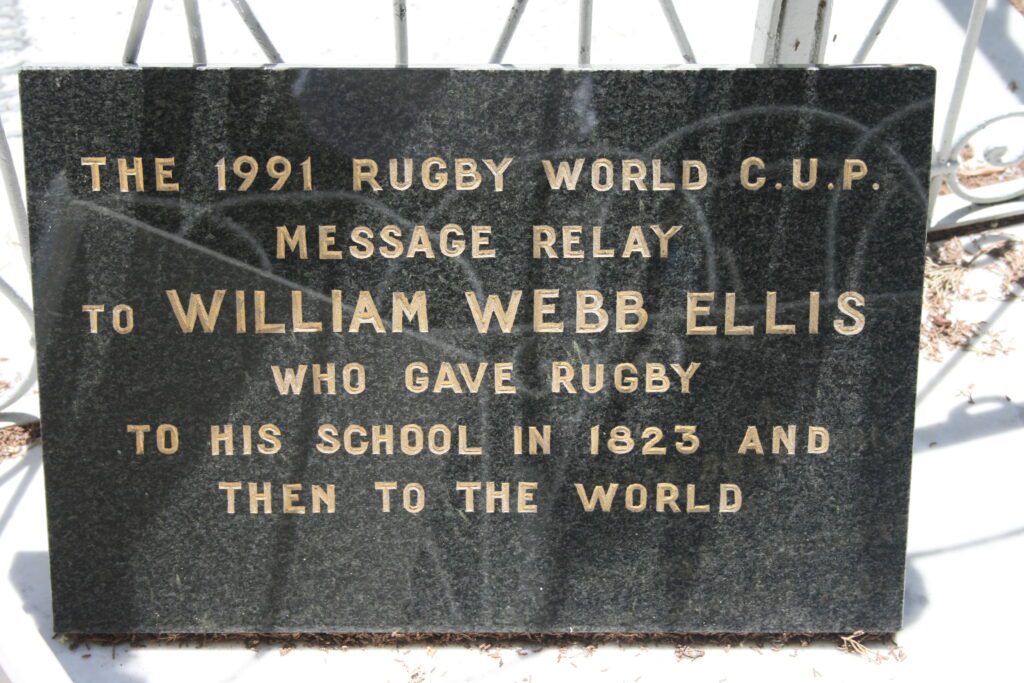

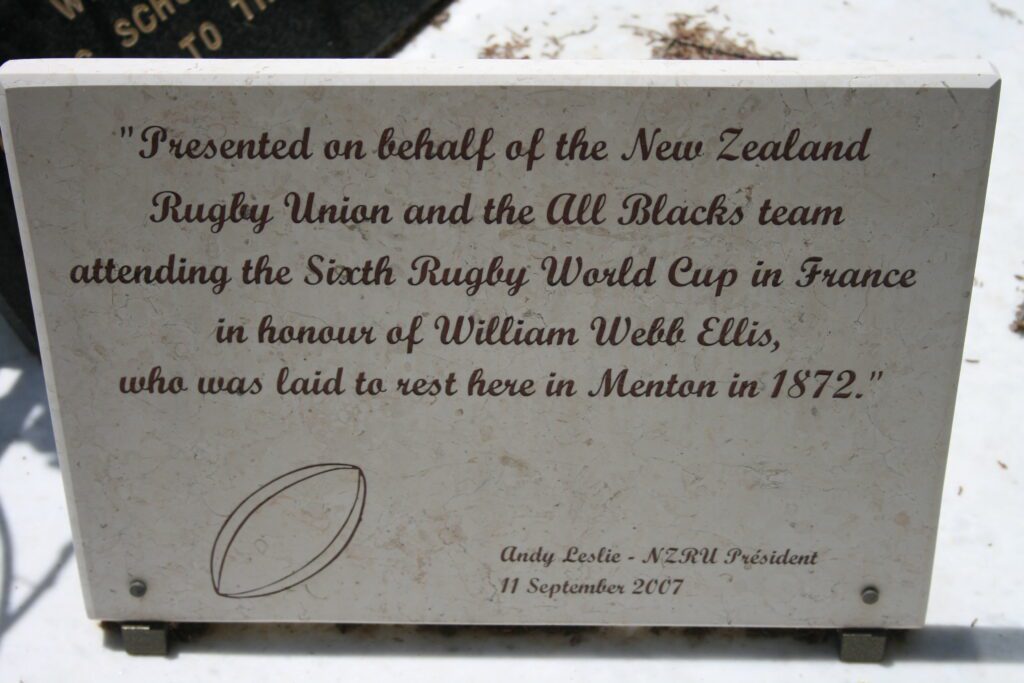

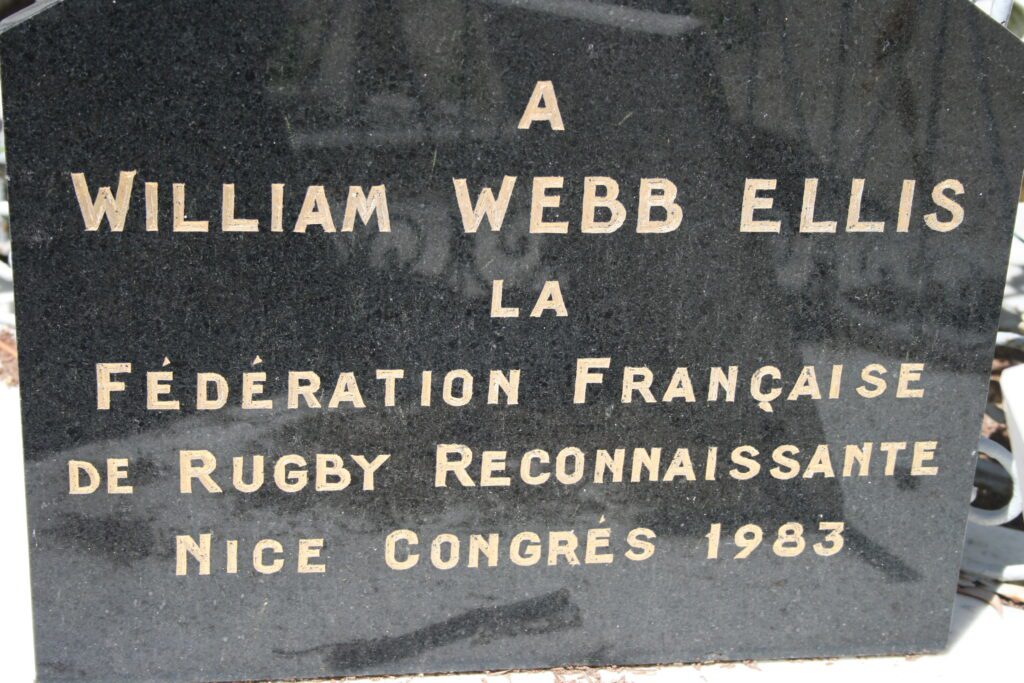

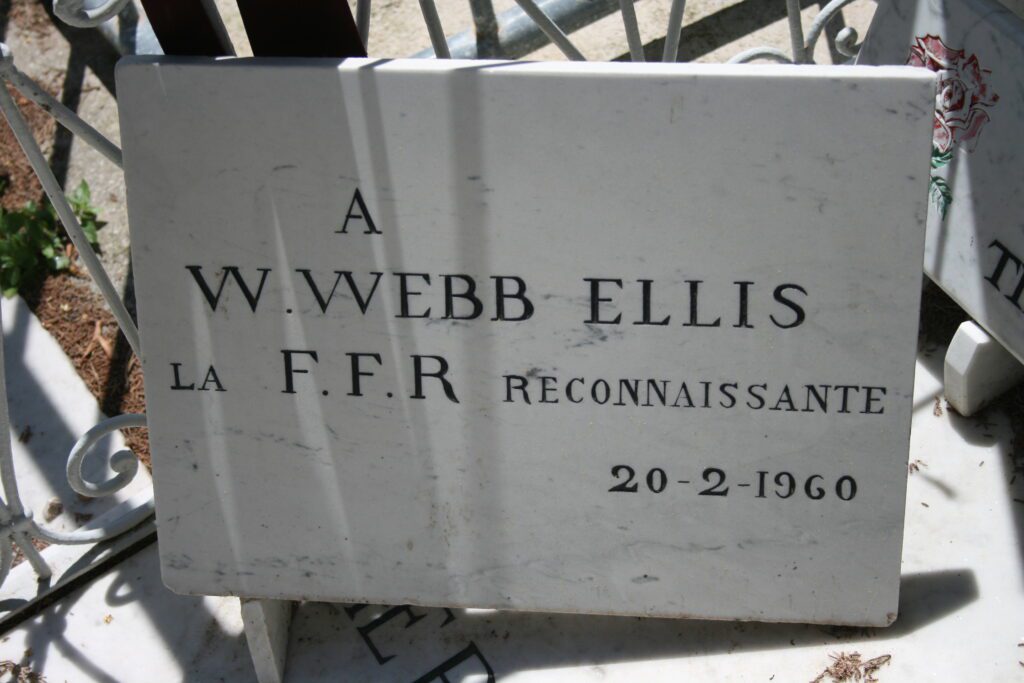

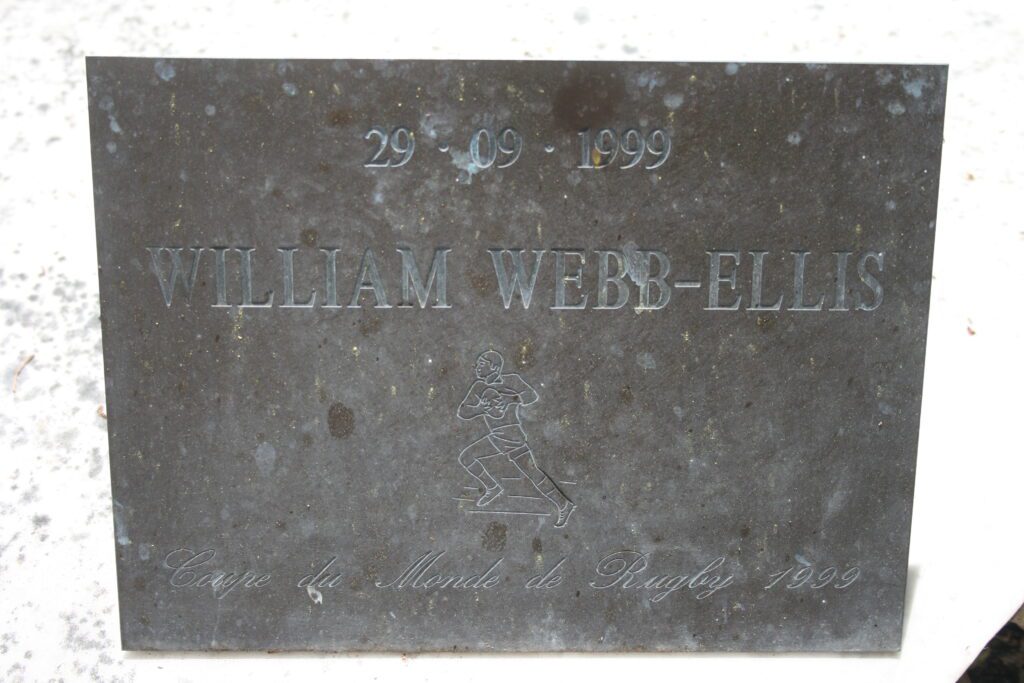

The small plaques presented by rugby teams and enthusiasts pay further tribute to this achievement:

Here lay the man hallowed by rugby enthusiasts around the world. He attended Rugby School from 1816-1825 and is credited with picking up the ball in a school football match of 1823 and running with it thus inventing the new game, whose agreed rules were later written down by boys at the school in 1845.

The veracity of this story is however in some doubt. It did not surface until 1876, more than fifty years after the putative event, and four years after the death of Webb Ellis. In the intervening years no one seems to have heard it. Its origins lay with Matthew Bloxam, Old Rugbeian, and antiquarian of Rugby, who claimed to have learnt it from an unnamed source. In 1895 when the Old Rugbeian Society investigated the story they were unable to find any first-hand evidence of the occurrence. Contemporaries of Webb Ellis did not remember the infamous match and others recalled that running with the ball, though not unknown, both before and after 1823, remained forbidden in the 1830s.

Moreover, almost concealed beneath these new stones, the original flat grave marker makes no reference to rugby, recording only the death of the rector of a London church.

It is indeed improbable that the actions of a single boy changed the game and more likely that it evolved gradually. Some authorities* go further suggesting that the 1895 investigation was an attempt by Rugbeians to assert their school’s authority over the sport at a time when they were losing control of it following the schism between rugby league and rugby union, and that for this they needed a specific character and a good story. Webb Ellis’ relative obscurity for the rest of his life added to the mystique and he died entirely ignorant of the role posthumously attributed to him.

Back with the world’s oldest tournament. On the penultimate Saturday a triumphant shout reached me in the garden as England won 23-22 against Ireland who had been tipped for the Grand Slam. It was also drawn to my attention that Italy had defeated Scotland 31-29 in Rome. This was Italy who had earlier lost 36-0 to Ireland, before beating Scotland, who beat England, who had just beaten the Irish: it was results like these that made the tournament so fascinating. I glazed over.

Today the tournament ended with Ireland winning the championship, albeit no Grand Slam. The beer bottles are in the recycling, the wine restored to its usual place, the television quiet, and on the Cote D’Azur an oblivious William Webb Ellis slumbers on.

*E. Dunning and K. Sheard, Barbarians, Gentlemen, and Players: A Sociological Study of the Development of Rugby Football (1979)

See also Michael Aylwin, Webb Ellis didn’t even invent rugby, so why is his name on the World Cup? in The Guardian 16 September 2019. Feelings run high on this issue.