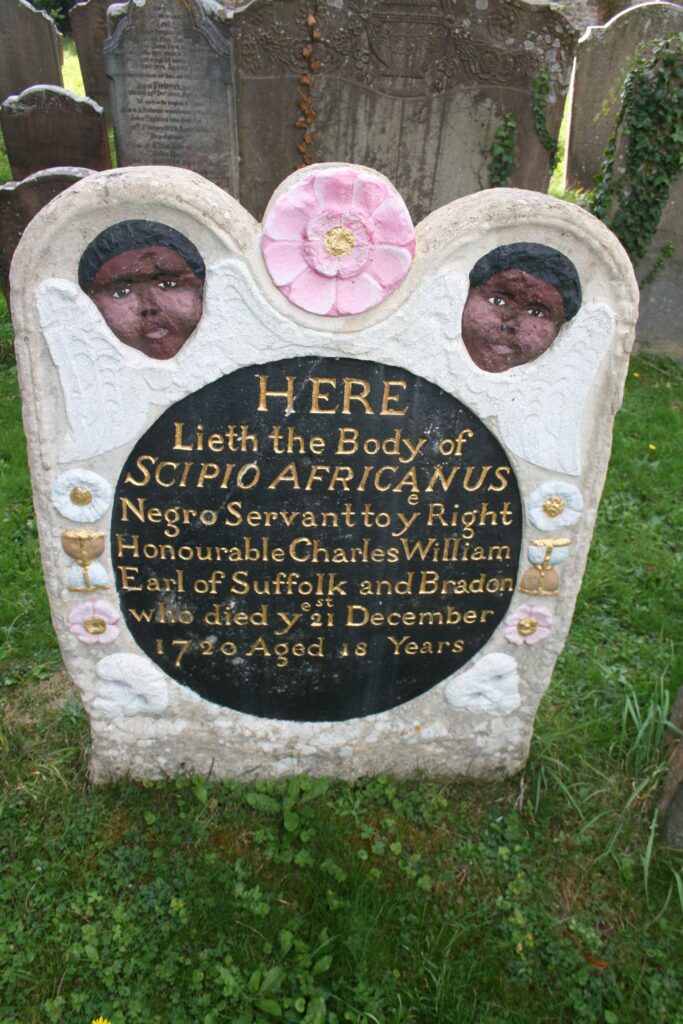

Unlike Scipio Africanus and the Beautiful Spotted Boy not every incumbent of England’s Foreign Fields arrived here under coercion. Prince Lee Boo and Thomas Caulker were both encouraged by their families to pursue schooling in England; sadly, both died young.

Prince Lee Boo

Prince Lee Boo was the second son of a former Ibedul or high chief of Koror Island in the Palau Island group in the western part of the Pacific Ocean. In 1783 Captain Henry Wilson, a trader for the East India Company, and his crew were shipwrecked on the rocks off Ulong Island . They were rescued and given hospitality by islanders from nearby Koror who spent three months helping them to rebuild their ship. The Ibedul, whose title they misinterpreted as Abba Thule, thinking this was his name, asked them to take Lee Boo back to England with them to further his education. Lee Boo lived with Wilson’s family in Rotherhithe and attended school there but tragically contracted smallpox and died at the age of twenty.

Wilson held Lee Boo in high esteem and during his brief time in England the young man captured the public imagination. He was feted, books and poems were written about him, and illustrations produced. Many of these productions however were patronising. Lee Boo was portrayed as a noble savage, an exotic curiosity, and his reactions to things which he had not seem before – mirrors, horses, oranges – were a subject of condescending amusement.

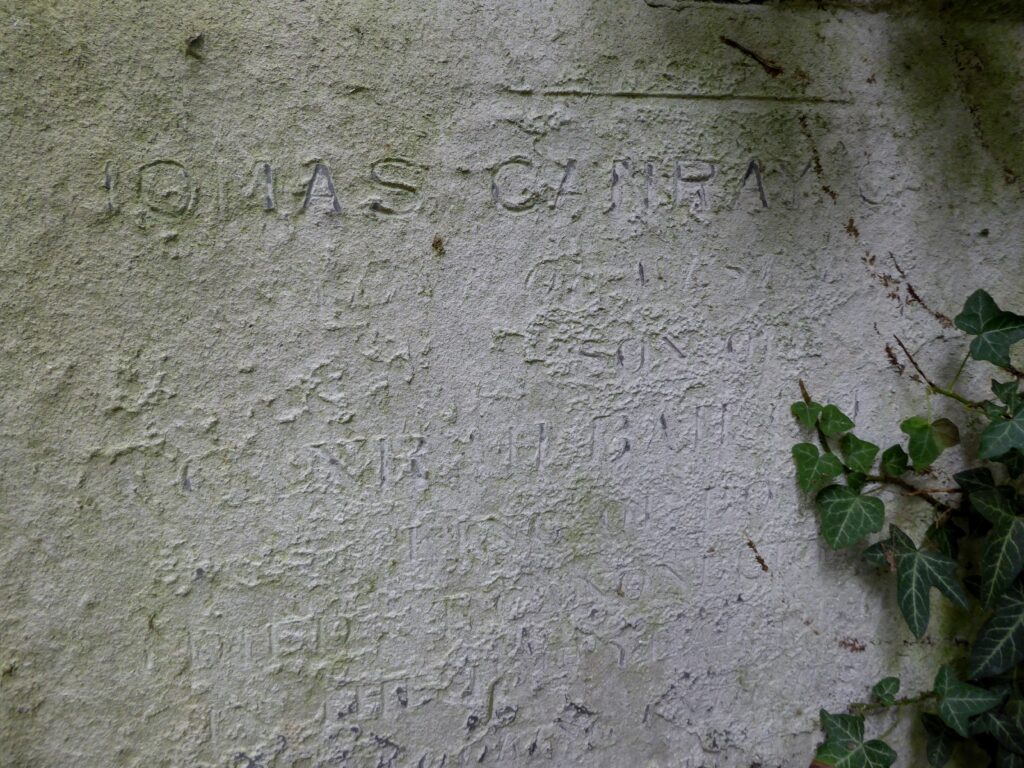

The Prince was buried in the Wilson family grave in the churchyard of St. Mary the Virgin Rotherhithe, SE London. The East India Company paid for his tomb and the inscription on the top. The very worn script reads:

To the memory of

Prince Lee Boo

A native of the

Pelew or Palos islands

and son of the Abbe Thulle,

Rurack or king of the

Island Coorooraa

Who departed this life

on 27 December1784

Aged 20 years.

This stone is inscribed by

The Honourable United

East India Company

As a testimony of esteem

For the humane and kind

Treatment afforded

By his father

To the crew of their ship,

The Antelope,

Captain Wilson,

Which was wrecked

Off that island on the night

Of 9th August 1783.

Stop reader. Stop. Let nature claim a tear,

A prince of mine, Lee Boo, lies buried here.

In 1984 a service was held on the two hundredth anniversary of his death and visitors from the Pacific Islands planted a gingko tree.

Thomas Caulker

Thomas Canray Caulker (1846-59) was descended from a wealthy, mixed race family: on the one side his namesake Thomas Caulker, an Anglo-Irish trader and colonial official with the Royal Africa Company, and on the other a Sherbro princess, Seniora Doll. Through this marriage in the seventeenth century the Caulkers had become hereditary chiefs of Bompey in what is now Sierra Leone. By the eighteenth century they had also become major slave traders.

In the nineteenth century however Thomas’ father Richard Caulker, also known as Canrah Bah Caulker, had aligned with the abolition movement to suppress the slave trade in the Sherbro country.

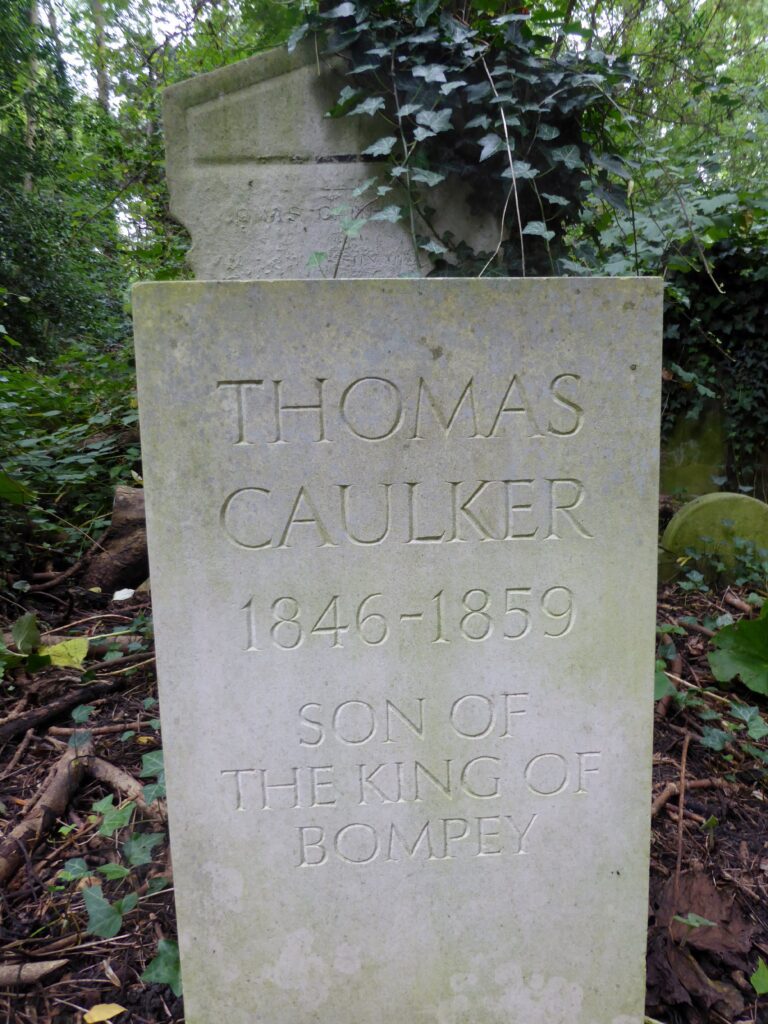

In line with other affluent African-European families Richard Caulker sent his son to London to acquire a Christian education. Thomas lived with the reverend JK Foster and his wife in Islington and because he suffered with severe eye weaknesses was sent to a school for the blind. Other medical problems however led to his death at the age of thirteen and he was buried in Abney Park Cemetery in Stoke Newington. His original stone is weathered almost beyond reading and is fast being consumed by ivy, but a new marker placed by the Abney Park Trust bears the bold legend:

THOMAS

CAULKER

1846-1859

SON OF

THE KING OF

BOMPEY

Far from home, Lee Boo and Caulker lie, the one in a London churchyard beside the Thames at Rotherhithe, the other amongst the tranquil woodlands of a nineteenth century garden cemetery in Stoke Newington, their small plots now and forever a part of their tropical homelands.