“ Jane Austen,” whispered the volunteer guide raising a weary eyebrow, “slipped in quietly at nine o’clock in the morning without disturbing anyone.” In the Cathedral a brass band was loudly, and repeatedly, rehearsing the national anthem. The harsh, strident tones ripped and tore through the early morning quiet, the band’s amplified performance penetrating every corner of the building. Already, when we entered, our bags had been painstakingly searched by two assiduously polite but resolute police officers. Their dogs patrolled the longest nave in Europe, sniffed warily at the chantries of Bishops Beaufort and Waynefleet, eyed the twelfth century Winchester Bible with suspicion, and pawed gingerly at the Tournai font.

“Military funeral tomorrow,” our guide continued sotto voce. “The cathedral will close soon for a full rehearsal.” Waving his arm at the array of memorials which line the great stone walls, he sighed, “ All high-ranking military, clergy and politicians, and all reputedly endowed with moral excellence and effecting heroic deeds.” He looked sceptical. “ No ordinary people.” He paused. “ And they didn’t even mention on Jane’s stone that she was a novelist,” he added indignantly.

We fled the noisy, disturbed cathedral, and passing rapidly through the Cathedral Close, awash that morning with police and military personnel, vehicles, and equipment, arrived in College Street. There we paused before the house where Jane Austen rented rooms during the last few weeks of her life in 1817, having come to Winchester to be close to her surgeon.

Then, abandoning the town, we followed Keats Walk to St. Cross Hospital. When Keats stayed in Winchester in 1819 he took his daily walk across the water meadows, and it was here that he composed his ode To Autumn. Our morning too was misty, with soft muted autumn sunshine just beginning to burn through, swans moving stately on the chalk stream and herons still as statues.

At St. Cross we explored the quiet complex of medieval buildings founded in 1136 by Henry of Blois. Church, Alms-houses, and Hall are all still in use. In the Master’s garden we found glowing herbaceous borders, cyclamen pushing through the grass beneath the sycamore trees, a dappled lake with a gentle fountain.

They still offer the Wayfarer’s Dole at St. Cross, but not feeling ourselves entitled, we joined instead a group of Friends and Brothers of St. Cross for tea in The Hundred Men’s Hall. There was a woolly tea-cosy on the pot, a choice of homemade cakes, and we were introduced to the Warden. Truly I felt myself in Anthony Trollope’s Barchester.

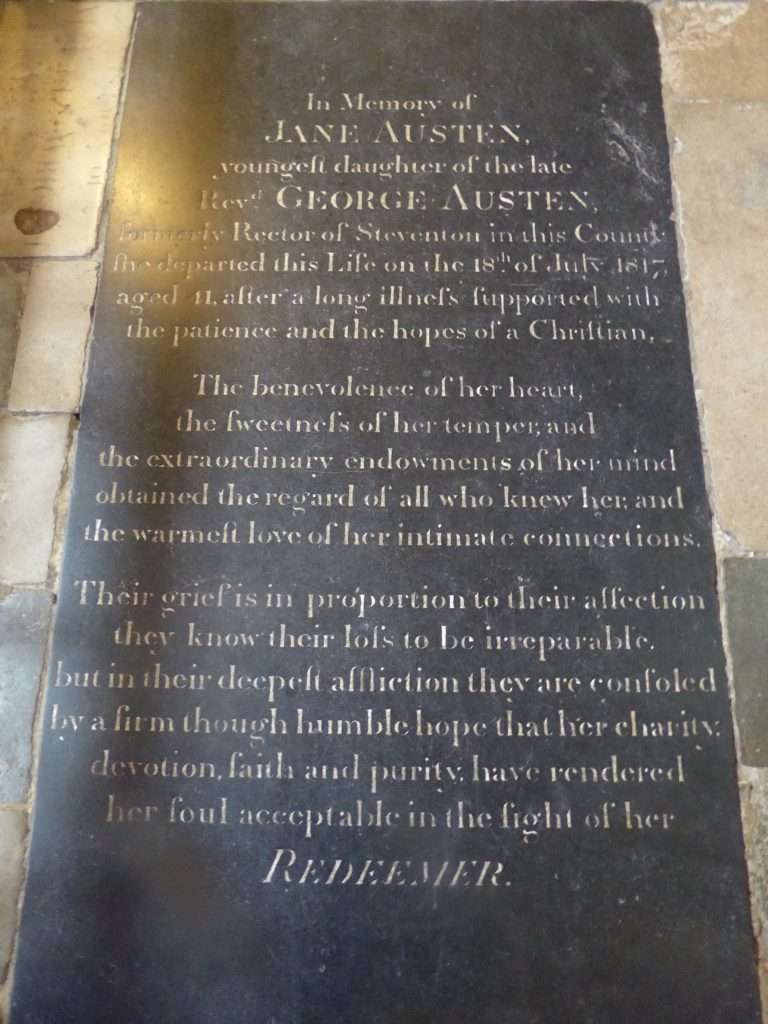

We returned another day to the Cathedral, when only its quotidian bustle rippled the surface, to pay our respects to Jane Austen. She lies beneath a dark stone slab on the floor of the north aisle. Here Keats, with only two years to live himself, walked up and down reading his letters from Fanny Brawne. And if the site occasions sadness for the early deaths of both writers, this is mitigated by profound gratitude for the treasures they left behind.

Jane’s mere presence here in a place generally reserved for the triumvirate of senior military, clergy, and politicians, is surprising. Speculation suggests that someone in the Austen family Knew Someone who Knew Someone With Influence. Her epitaph, composed by her brother Henry, certainly makes no reference to her literary achievements focusing rather on a conventional recitation of her qualities:

In Memory of

JANE AUSTEN

youngest daughter of the late

Rev. GEORGE AUSTEN

formerly Rector of Steventon in this Count.

She departed this life in the 18th of July 1817

aged 41, after a long illness supported with

the patience and the hopes of a Christian.

The benevolence of her heart,

the sweetness of her temper,and

the extraordinary endowments of her mind

obtained the regard of all who knew her and

the warmest love of her intimate connections.

Their grief is in proportion to their affection

they know their loss to be irreparable,

but in their deepest affliction they are now consoled

by a firm though humble hope that her charity,

devotion, faith and purity, have rendered

her acceptable in the sight of her

REDEEMER

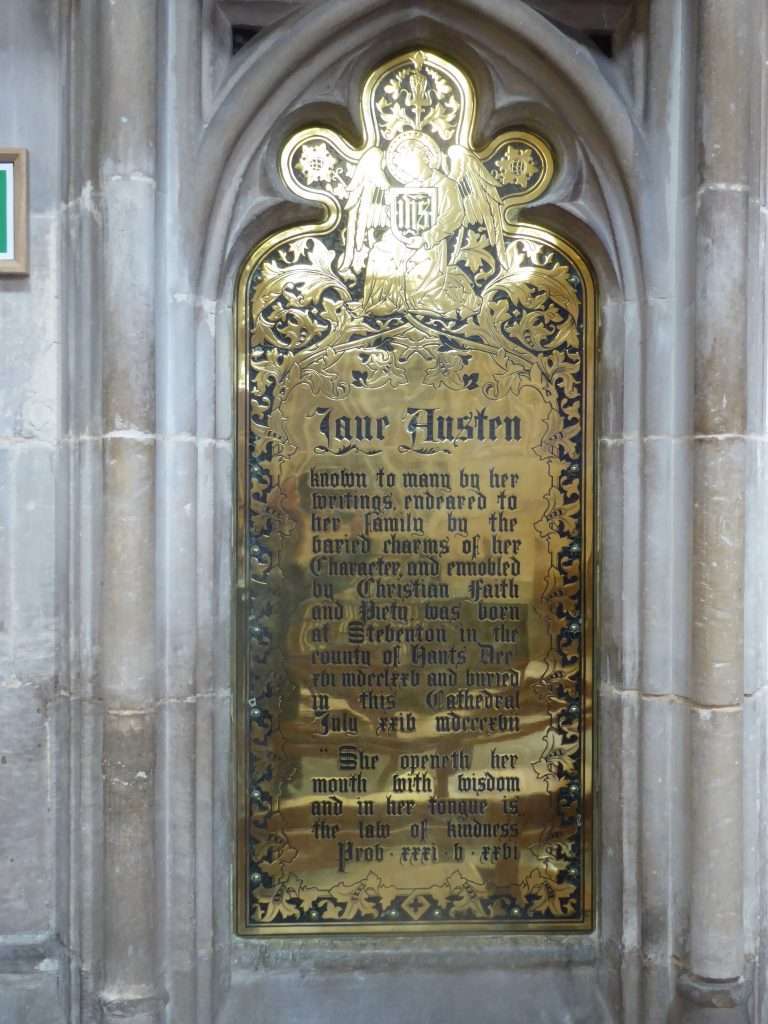

In 1872 Jane’s nephew placed a memorial brass on the wall, on the left of the grave, which acknowledged, with some understatement, that she was “known to many by her writings.”

A memorial window, financed by public subscription, joined it in 1900, but the window too is underwhelming, and Jane’s grave is overshadowed by the bombastic memorials trumpeting the achievements of the Pillars of the Establishment. But I prefer her plain black stone to these monumental, cold, white sepulchres, just as I valued the tranquillity of St. Cross above the undoubted splendour of what is undeniably one of England’s most magnificent cathedrals.

Welcome